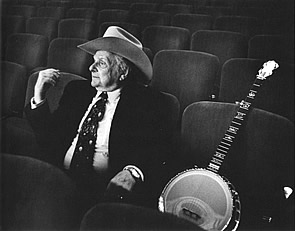

When Ralph Stanley won the Grammy award for best vocalist in 2001, no one was more surprised than I, except possibly some of my students. Along with Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers are touchstones in the old-time, bluegrass, and country music course I’ve offered at Brown for the past fifteen years. About ten years ago it occurred to me that in addition to teaching the history of bluegrass it would be fun to try to get the students to sing it. They might as well learn from the best, I thought; and so generations of Brown students have gone around singing Ralph’s tenor parts and Carter’s melodies. Few had heard of Ralph Stanley before trying to sing like him, but afterward I doubt many forgot him, or his haunting voice—a voice well known for more than fifty years, if only to bluegrass aficionados, before he hit the big time in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, with “O Death.”

The magnificent tone quality of Ralph Stanley’s voice was born, not made; but he learned his curves, glides, and falsetto catches as a child from hearing the music of his family’s Primitive Baptist Universalist denomination in church and at home. Popularly called the No-Hellers, because they don’t believe there is a hell, this obscure religious group from central Appalachia sings very much like the Old Regular Baptists (see Dorgan, and Cornett, Titon, and Wallhausser); and of course the singing style and tune stock is the same mixture of English and Scots-Irish that came into the southern Appalachian Mountains with ballads and fiddle tunes, though it’s likely that some of the style’s characteristic melismata, free rhythm, and slow tempo were fashioned in a black/white musical interchange.

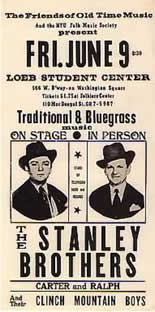

Why Ralph Stanley, and why today? He has, after all, long been recognized as a major artist in bluegrass. The Stanleys, who began recording in the late 1940s, were among the most popular early bluegrass bands, performing on fifteen-minute segments on local radio stations and playing in small venues throughout the South. Bluegrass never made much impact on the national country music charts, however, and by the late 1950s it was in decline, victimized by rockabilly and easy-listening country music. Just then it entered a revival phase and found a new audience among (sub)urban, middle-class, college-educated young men. Part of the 1960s folk revival, this bluegrass revival began the series of festivals that brought under one tent many star bluegrass groups and featured the “parking lot picking” that made, and still makes, bluegrass a music for serious amateurs as well as professionals.

Carter Stanley died in 1966; after Ralph emerged from mourning, he continued his music as Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys. Over his fifty-year career he has recorded more albums than any other bluegrass musician—185 is a ballpark figure. His popularity spans at least three audiences: the original bluegrass audience in the upland South in the 1940s and 1950s when it was a regional niche music; the added bluegrass revival audience from the late 1950s to the present; and the audience that was introduced to him through O Brother and the recent albums where he is paired with other “roots” musicians. It is useful in this context to distinguish him as a “source” musician, an old-timer who has profoundly influenced younger musicians down through the years. What do these three audiences hear in his voice? Each projects its own images of authenticity onto him.

In the 1940s and 1950s the bluegrass audience understood Stanley as one of their own. He sang and played their music, but he did so in a virtuosic way. Radio and concert recordings from the period reveal that The Stanley Brothers also participated with gusto in the stereotypical stage humor that had entertained people in the rural South and Midwest for decades—a humor based on stubborn animals, dumb farmers, and ignorant city folks. The Stanley Brothers often entertained at rural fairs, stock car races, and other regionally appropriate venues. As a part of their shows, one of their band members performed sound effects of daredevil auto rides. What their audience saw in them, then, were good old boys as they wanted to be, in control and command of a tradition they identified with. The Stanleys projected not only good-old-boy virtuosity, but also good-old-boy sentiment. Their concert repertory regularly included waltzes, gospel songs, and secular songs whose lyrics reveal that peculiar combination of wanderlust, guilt, and memory of mother and home that construct the textual archetype of bluegrass and country music.

The (sub)urban folk revival’s interest in bluegrass, particularly in the 1960s, shared a number of things with prior folk revivals: a distaste for bourgeois values, an antipathy toward the industrial (or post-industrial) state and mass society, and a romantic view of rural life as more natural and therefore more authentic. Bluegrass, of course, is viewed as a product of that more authentic life. In other significant ways, though, the bluegrass revival was, and is, different from previous folk music revivals. For one thing, the bluegrass revival utterly lacked the nationalism characteristic of European revivals and the racism of the earlier American Appalachian music revival so thoroughly dissected by David Whisnant, though it did not shrink from sexism of the predominantly male bluegrass musical culture. For another, as the revival continued, some of the revivalists who became performers were adopted into the bluegrass culture, a process that continues today. Participation in performance and learning from tradition-bearers like Ralph Stanley is not limited to the bluegrass revival, of course; it is characteristic of Euro-American folk revivals of the later twentieth century.

Many of the people who participate in the bluegrass revival come from backgrounds far removed from the Stanleys’ rural upbringing in central Appalachia, and sometimes the cultures clash in ways that make it difficult for people to inhabit the same community, other than as a community of music-makers. Yet the romantic impulse in a folk revival is always directed broadly at a way of life represented by music, and not just narrowly at folk performance. A second paradox of this particular revival is that while rejecting the bourgeois values of the corporate world—including the values of getting and spending—many revivalists engage in an excess of bluegrass consumerism, connoisseurship, and a passion for collecting recordings and musical instruments. Finally, as bluegrass is a virtuosic music, difficult to sing and play well, and requiring years of practice even to reach competence, the bluegrass revival embodies both a competitiveness characteristic of music in America and at the same time, at its best, an ideology that denies competitiveness—after all, in a community of musical virtuosos, the good old boy does not try to show anyone up.

It is difficult to imagine that the bluegrass revival’s romantic pastoral could survive any reasonably intelligent viewing of the O Brother movie. It was discussed endlessly on the various American roots music listservs when it appeared, and if the fiddle-l list is a fair representation, the fiddle players (some old-time, some bluegrass, mostly revivalists) who contributed could be divided into those who felt the movie perpetuated the hillbilly stereotype and those who felt it parodied it. Tellingly, no one used the word “authentic” in connection with the film, except perhaps to deny authenticity—the music, for instance, wasn’t quite right for the time and place, though on another level this music appears timeless. Long-time Ralph Stanley appreciators were appalled to hear his voice coming out of the Klan’s leader. How could anyone take this movie’s story literally? Indeed, this is why the Coen Brothers made so much of the parallels with the Odyssey—rather zany, I thought.

It’s hard to know how many people who made the O Brother album a best-seller despite a lack of radio and television airplay actually saw the movie, but I suspect a great many of them did. Some claimed it significant that sales were achieved despite Nashville’s indifference. No doubt, but in the O Brother film there also are parallels to the reception of another film, The Blues Brothers. In both, a public that knew little about roots music was introduced to these things by means of enormously popular cultural icons—John Belushi and Dan Ackroyd in one instance, George Clooney in the other. Many who bought the O Brother album do not habitually listen to country music; to them it made no difference that the songs were seldom played on country music radio or TNN. Yet, whereas The Blues Brothers showed James Brown, Aretha Franklin, John Lee Hooker, Cab Calloway, and members of the Muscle Shoals Stax/Volt rhythm section performing and acting in the film, Ralph Stanley and most other O Brother performers were but disembodied voices on a soundtrack, making it easier for the viewer to disengage the film from these musicians and give the soundtrack album a life of its own.

T-Bone Burnett, producer of the music for O Brother, is responsible for the eponymous Ralph Stanley, a year 2002 release meant to take advantage of the singer’s new popularity. Listeners familiar with his earlier work will be badly disappointed. Ralph Stanley nowhere plays banjo, his singing sounds weak, and there isn’t a single bluegrass arrangement. Simplistic rather than simple, groove-less despite the presence of all-star musicians, Burnett’s production evokes none of bluegrass’s drive and tension, and provides only a faint echo of Ralph Stanley’s chilling virtuosity, as in “Lift Him Up, That’s All.” Anyone interested in seeking out the best of Ralph Stanley—and his best is superb—should listen to the Stanley Brothers’ Columbia recordings from the years 1949–51, and to the Rebel recordings Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys made in the 1970s.

Students at Brown usually have heard me introduce Ralph Stanley as an archaic figure: “Here is someone who at the age of 30 sounded as if he were 70, and now that he is 70 he sounds like he is 170.” (He is 75 today.) I have pointed out that in interviews Stanley takes pains to locate himself within the older traditions, seeing himself not as an innovator but as a perpetuator of old-time music in its more modern representation (bluegrass). It now seems he was ahead of his time, or that the time cycle has for the moment caught up with him. In one view, the Ralph Stanleys and Robert Johnsons of the world labor in their vineyards, waiting to be discovered, to be honored and celebrated, to wear the mantle of authenticity. In a different view, authenticity is an easy target for deconstruction. After all, for fifty years Ralph Stanley was aiming for commercial success, and the opportunity to succeed big time finally came his way. More power to him. It is not as if the “alternative” media industry created cultural icons out of the Primitive Baptist Universalists from whom he learned to sing; and I won’t hold my breath until they do. And no one will be more surprised than I when they, or the Old Regular Baptists (whose music the Brown students also learn), are singled out for a Grammy award.

Next Essay (link to Williams article)

Works Cited

Cornett, Elwood, Jeff Todd Titon, and John Wallhauser. Liner Notes. Songs of the Old Regular Baptists: Lined-Out Hymnody from Southeastern Kentucky. Smithsonian Folkways, 1997.

Dorgan, Howard. In the Hands of a Happy God: The No-Hellers of Central Appalachia. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997.

Whisnant, David. Modernizing the Mountaineer. Boone, NC: Appalachian Consortium Press, 1980.

—. All That Is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

Discography

Stanley, Ralph. Ralph Stanley. Columbia, 2002.