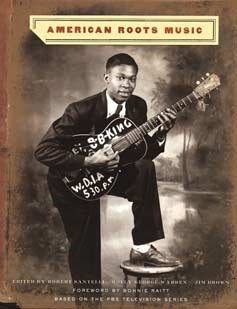

“That’s authentic! That’s real!” the late R&B singer Rufus Thomas says during the opening sequence of the PBS series American Roots Music. Other talking heads in this series concur: roots music is “not disposable pop fluff,” Marty Stuart says. Ricky Skaggs observes, “[it] may flow over here into commercial music,” but it always “connect[s] us to the old.” It’s “the root system”; it “gives the entire new century a canvas to paint on.” While impressionistic in the extreme, these definitions, applied liberally or just impartially, might have led the producers to embrace swing, hip-hop, Al Jolson, klezmer, and who knows what, with resulting verve. Instead, American Roots Music limits itself to a familiar trio, blues, country, and gospel; a narrow selection of those styles’ antecedents and beneficiaries; and (in the final hour) Cajun/zydeco, tejano, and Native American music, whose rescue from near oblivion is presented as having been inspired by the preservation of the big three.

The tale, in other words, is really that of folk revival and cultural preservation, as seen exclusively from the official and institutional vantage points that the revival has achieved during the past thirty years. Roots music was permanently defined, for the purposes of this series, in the early 60s at the Newport Folk Festivals; its meanings have been nurtured, developed, and expressed since then by such institutions as the Smithsonian, the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the Library of Congress, and public broadcasting, whose mandates involve not only encouraging the music’s preservation but also—and decisively for the nature of this series—instructing the public in its history and meaning. An evocation of Newport serves as the series’ emotional and intellectual climax; that climax is followed by a long denouement leading to, among other things, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. Because the series itself represents yet another expression of the folk revival’s successful progress from festivity to officialdom, American Roots Music ends up squandering a wealth of amazingly fresh archival material on what turns out to be an eerily tuneless paean to its own makers, funders, and mentors.

Nothing could be more boring, but there is an infuriating irony involved too, with ramifications for current and future manifestations of folk revival. In a breathless Procrustean lather, American Roots Music permits itself repeated bouts of disingenuousness, as it lops off vital elements and stretches others painfully thin. The curators on whom we rely to present this music in popular and accessible form seem so preoccupied with enshrining what they consider authentic, and eradicating what they don’t, that they have removed all conflict and personality—all life, really—from this vision of the music they are supposed to be committed to preserving.

An especially close relationship to folk tradition, the series both states and persistently implies, is what makes the selected music “roots.” The introductory segment points out that the music—with known authors and mass-mediated transmission—is not folk in the musicological sense. Still, the voiceover narration, as read by Kris Kristofferson, defines roots music as grounded in “folk songs, hundreds of years old and not written down,” and throughout, the series directly equates roots with folk: “folk, or roots music”; “Ralph Peer was looking for folk music”; “a thing called folk music, or roots music.” The introduction to the beautiful accompanying coffee-table book describes roots music as an “updated and expanded evolution of American folk music” and commercial media as an addition to oral transmission. According to this essay, a roots artist is an emissary from a folk community, consciously carrying on American musical traditions, embracing technology in order to share those traditions, chronicling gender and class relationships and racial tensions. Since nothing in the history of blues and country—often even as presented in this series!—comes close to bearing out that fanciful description, American Roots Music resorts to tortuous pathways in illustrating its authors’ favored notions about the proper role of music in tradition and community.

Blues, for example, is “founded on an ancient African call-and-response style of singing.” Having defined blues only in this way, the series is off to the Delta, thence to Chicago and rock and today’s intermittent lionizing of electric blues. Describing this strain of guitar-accompanied blues as having come almost exclusively from call-and-response singing and ignoring all non-African sources of call-and-response might be explained as necessary oversimplifications. But the series presents the Delta-Chicago-Stones arc as blues at its most essentially bluesy: the music of Bessie Smith is described as “a particular form” of blues, “sung by the soloist fronting jazz orchestras.” This vacuous distinction between blues and a jazz-backed variant allows the series not only to ignore the likes of Ma Rainey (associated here exclusively with jazz), Joe Williams, and Helen Humes, say, but also to neaten almost into nonexistence the messy creative relationships that once prevailed among ragtime, jazz, and rural and urban blues. As the blues historians involved in the project surely know, Delta and other country players were often adapting reed-brass-keyboard music to guitar, and attempts to give country blues especially primal links to Africa are notoriously problematic.

This blues story culminates, post-Newport, in the triumphant assertion that the great Chicago artists are “still revered in the clubs.” But reverence hardly describes the circumstances in which those artists created their art: today’s blues bars represent a potentially interesting shift (at least partly an effect of folk revival) in social, racial, and class conditions. The series pretends this shift doesn’t exist even while giving us blues-in-the-schools, with kids in a classroom singing “I’m a man” from “Mannish Boy.” The scene is charming and funny; it’s also such a far cry from the spirit of Muddy Waters and Son House that it unwittingly contradicts the triumphant suggestion that blues has been revived and kept alive and now can never die. The celebration seems really to be for the permanent establishment of blues as venerable and educationally valuable, its history an important set of lessons that every boy and girl should learn in class. (The lecturing tone of some of the talking heads enhances this feeling.) Delta and Chicago blues themselves, and all the adult intensity, sensitivity, and sexuality that the archival material so beautifully dramatizes—this sequence might as well be saying—no longer really exists.

The filmmakers include Jim Brown and Sam Pollard, experienced students of American vernacular history; their advisors include Bernice Johnson Reagon, Charles Wolfe, Pete Daniel, David Evans—these really are among the great experts on blues. Yet the series places the origins of blues exclusively in ancient African singing and says of jazz only that it is “based on blues.” It deftly elides the way rock and roll did not bear out but temporarily sidelined Muddy Waters’s American career; it ignores John Hurt’s having played at least as much in a ragtime as in a “folk” style. The really devastating thing is that these can’t be mistakes.

The filmmakers are surely also aware of the irony in playing “Wildwood Flower” while presenting the Carter Family and their repertoire as steeped in the oldest traditions, which the series has called “not written down.” The Carters’ music is repeatedly described as “old”—and “Wildwood Flower” certainly qualifies. But as many people know,“Wildwood Flower” doesn’t spring from Anglo-American folk music but was composed by professionals, as “I’ll Twine ‘Mid the Ringlets,” published for an urban Yankee audience in the mid-nineteenth century. In failing to mention the song’s origins while insisting on the Carters’ back-country aura, the “past being brought up into the present” (as the series describes the Carters’ music) is an entirely different past from the one on which their music—and country music as a whole—was actually founded.

A compelling aspect of early recorded country is the glimpse it affords of rural Southerners’ adapting the urban parlor vision of rural life, making its floweriness their own, embracing the Victoriana that was growing outmoded in cities, and endowing country with trademark weepiness—a process at least as important to the origins of hillbilly as transmission of folksong. And the Carters combined urban Victoriana with their own versions of ragtime and blues, not then “old” at all. The series further declines to acknowledge that much banjo-fiddle music collected in the Appalachians has antecedents in compositions by Stephen Foster and others for the Northern minstrel stage, which itself came from another kind of collecting, the appropriation and parody of black slaves’ music. (Slave music, in turn, came partly from both parody of and compliance with the formally composed music popular among slave-owners.) This is the crippling yet apparently necessary omission at the heart of American Roots Music. The series makes much of the impact of roots music on mainstream pop but persistently denies the decisive impact of theatrical, parlor, and other commercial, composed, and published forms on rural Southern music, both black and white, in the centuries before the advent of recording. The decisive impact, that is, of mainstream pop.

Uncle Dave Macon is thus described as a preserver of “rare folk ballads.” Though almost entirely untrue, the designation gets tossed in as if in desperate hope of legitimizing Macon’s importance to country music. The series must acknowledge Macon’s broad vaudeville-minstrel style, but by manufacturing a link to some archaic Anglo-America, the filmmakers resist acknowledging how that style undermines their precepts. There’s no choice but to admit that Jimmie Rodgers, too, played sentimental and music-hall material—though the central place of ragtime in his repertoire is ignored, and Rodgers’s background in blackface is censored. Minstrelsy may be the most ragged wound in this story: you’d never know that Rufus Thomas began his career in the fabled Rabbit Foot Minstrels (his stories might have been riveting), or that blackface characters were common in early hillbilly bands. And without minstrelsy, it’s hard to imagine any honest or even interesting history of either blues or country.

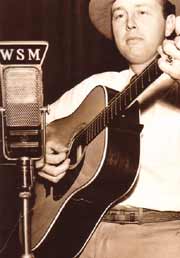

It goes on. Hollywood cowboys get in where other pop stars wouldn’t, maybe because John Lomax’s cowboy songbook starts the revival story. Appalachian and blues elements in Bob Wills’s music are emphasized over jazz elements. The term “bluegrass” is said to have been given to the music by Bill Monroe, who at least as late as the early 50s, when the term was first coming into common use, would have angrily denied that any such music existed. Extreme racist Henry Ford’s crucial role in the spread of fiddlers conventions is never mentioned. Ragtime goes unacknowledged, yet again, in Merle Travis’s music—and Travis’s folksier hit songs, lauded in the series, are not acknowledged as uncharacteristic attempts to benefit from the folk craze. Lefty Frizell’s vocal style is called influential for bringing not pop stylizing to country but “the Southern drawl” to music. Elvis Presley, lauded by B.B. King and (in the recollection of Sam Phillips) Bill Monroe, appears never to have caused upset among either black or white musicians, just as bluegrass and honky-tonk seem always to have lived comfortably side by side, happy to be part of the “rich gumbo” that is American roots music. And the filmmakers know better.

The final hour addresses tejano, Cajun/zydeco, and Native American music. It thus recapitulates the progress of the folk revival itself, as in the late 60s and the 70s young revivalists delved into ethnomusicology and specialization, beginning careers that led to, among other things, this series. The folk revival has been presented in previous segments as crucial to the survival of country, blues, and gospel (in the approved styles): “Most Americans were still not aware of a thing called folk music, or roots music”—(a radically new conception of the folk!)—“but that was about to change.” The Newport sequence concludes by dubbing Doc Watson a “national treasure,” deftly connecting the folk revival’s triumph at Newport to its future connection with officialdom. Having established Newport styles in bluegrass, country, gospel, and blues as the roots canon, the series now turns to the salvation of other music.

Music of other cultures, that is. “All My Children of the Sun,” as the last hour is titled, dramatizes the claim that post-Newport efforts to preserve and popularize Cajun, zydeco, tejano, and Native American music have reinvigorated entire cultures. It’s not made overwhelmingly obvious that these forms “gradually became accepted as important cornerstones of American music,” or that, if they did, it’s to the undying credit of revivalist “history lessons,” as Marc Savoy forthrightly calls his accordion jam sessions. The Native American case is painfully weak. Nobody really thinks—least of all, no doubt, Native American musicians—that this music will ever get a fraction of the credit among fans of rootsy pop that zydeco and tejano do. The salient issues in Native American music are of another order than those in the other forms; the subject cries out for far less glib treatment than it can get here.

The mood and strategy of the last hour are epitomized by a clip of people sweatily cavorting in a bar to the Cajun-and-zydeco-influenced music of Steve Riley. Narration over the party: “It’s hard to imagine that thirty-five years ago this same community felt that its music had little value.” Hard indeed: that’s quite a statement to make about how any community ever felt; moreover, this rocking video moment doesn’t say much about how this community feels now. And if truths are buried in all the gushing, how would we know? “Wildwood Flower” has a particular history, and Joe Williams sang as much blues as Muddy Waters, and Bill Monroe didn’t give the name “bluegrass” to his music, and the filmmakers know it. What is really hard to imagine is how seriously to take anything in this last hour, which gives an unsettlingly, contradictory impression. In one way, this conclusion seems a patronizing dumping ground for music that it would be wrong to leave out. Yet in attempting to link the “roots artist”—that culturally authentic, socially sensitive emissary to modernity described in the book’s introductory essay—not only to current values of cultural education but also to the original development of country, blues, and gospel, the final segment also supplies pretext and specious justification for all the distortions that came before.

In the end, it’s not only the likes of Son House and Hank Williams whose energies the series tries to squeeze into the narrowest channels. The Lomaxes and Seegers and Peter Paul and Mary and those revolutionary Newport events, with all their passion, idiosyncrasy, and sheer eagerness for discovery, are subordinated, too, to orthodoxies used reflexively to certify the value of American vernacular music’s history. There simply must be a new way—at the very least a livelier and more honest way—to engage the dazzling wealth of art with which we’ve been blessed by musicians, collectors, entrepreneurs, musicologists, researchers, and others. The approach represented by American Roots Music has long grown, at best, calcified. Revival, anyone?

Next Essay (insert link to Howard article)

Works Cited

American Roots Music. CD Anthology. Palm, 2001.

Brown, Jim, dir. American Roots Music. DVD. Palm, 2001.

Santelli, Robert, Holly George-Warren, and Jim Brown. American Roots Music. New York: Abrams, 2001.