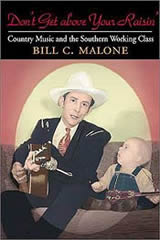

Bill C. Malone. Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2002. ISBN 0-252-02678-0. Pp. 393. $34.95 (cloth).

While I listen to “The Rock,” the opening song on George Jones’ latest CD, The Rock: Stone Cold Country (2001), I notice the lone sonority of the acoustic guitar that introduces Jones’ weathered voice singing about the complicated emotions drawn from the pleasures and sorrows of adult love and sexuality: passion, loss, and hope. Though I am submerged in my own painful memories of ending relationships once dear to me, the underlying groove beckons my body to seek a partner and dance the two-step in my living room to the music’s gradual eruption as each instrument enters the ensemble. As I euphorically dance, releasing those overwhelming emotions of grief with my imagined partner, Jones sings about simpler times, evoking sentiments of nostalgia. Within the broad context of longing for an existence outside of urbanity, the music portrays contrasting images of masculinity: the virile whiskey-drinking womanizer and the vulnerable worker who longs for a beloved and an escape from the entrapment of earning a wage. Jones’ philosophizing about the conditions of life extends to the spiritual realm as I switch CDs to It Don’t Get Better Than This (1998) and listen to the last track, “I Can Live Forever.” In the same fervent style and pulsating rhythm of his honky-tonk songs, Jones depicts the afterlife’s heavenly place of escape, serenity, and assurance of the continuity of one’s existence even after death.

Though George Jones is a legend—canonized by scholarship as well as the music industry itself—his music is not alone in evoking conflicting images of reality and escapism.  In Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class, Bill Malone deftly discusses the very layers of tension prevalent throughout country music and rooted in southern working-class culture. Malone’s work has been influential in shaping the stories scholars tell about the industry and music since the 1968 publication of his dissertation, Country Music, USA, which established a canon within the general narrative of country music.

In Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class, Bill Malone deftly discusses the very layers of tension prevalent throughout country music and rooted in southern working-class culture. Malone’s work has been influential in shaping the stories scholars tell about the industry and music since the 1968 publication of his dissertation, Country Music, USA, which established a canon within the general narrative of country music.

In Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’, Malone situates country music as looking backward to rural life that dissipated in the wake of industrialization. Through his explorations, Malone relies on W. J. Cash’s theory about how the paradox of hedonism/piety has been central to shaping the dynamics of southern culture from the defeat of the Civil War to the homogenizing effects of middle-class culture. While many working-class southerners may drink, dance, and carouse on a Saturday night at a local barn dance or honky tonk, on Sunday morning the same individuals may attend church and share a family meal with extended relatives. Depicting the tension between rurality and urbanity and the hedonism/piety paradox, Malone narrates how the major realms of country music—work, home, religion, rambling, dance, humor, and politics—function within the culture and play out in music.

As a scholar and musician who grew up in the south, Malone artfully draws his readers into a world with which he is intimately connected. He offers an astute understanding of southern, working-class society, specifically as it relates to country music’s portrayal of masculinity. His focus, however, at times does not critically address other aspects of southern culture and music. Though he mentions the influence of African American music in myriad ways, constructions of whiteness, and music written and sung by women, Malone does not delve into the complexities of racial and gendered identities with the same historical specificity he devotes to the ambiguities of white masculinity. Perhaps with the tools of social theory, Malone may have been able to unravel further the racial tensions and ambivalences in the south and examine the full participation of women in country music. Yet, despite these omissions, Malone admirably explicates many of the cultural forces that have shaped country music in particular and American music in general.

The conflicts surrounding urbanization resounded in many ways for both working-class southerners and in country music. Malone explains that with tenantry and sharecropping fading from the burgeoning railroad, coal, and oil industries, the south contained physical junctures where industrialization fused with the rural. This discordant relationship fostered a music that simultaneously voiced a longing for the autonomy associated with farming and negotiated the regimented lifestyles of oil field workers or coal miners. In “I’m a Small-Time Laboring Man,” his chapter on the realm of work, Malone elucidates the long tradition that includes Fiddlin’ John Carson, “who sang movingly about the honest farmer, to Willie Nelson, who had devoted much of his time and career to the crusade to save the family farmer” (37). Along with reinforcing the romanticism surrounding farming, many songs depicted the conditions and poverty of the working class. Merle Travis’s “Dark as a Dungeon” describes the perils of coal mining as well as the company store’s ambiguous ownership of the laborers’ soul, whose dependency upon the industry was “like a fiend for his dope, and a drunkard his wine” (43).

Merle Haggard, 1995. Photographer, Loyal Jones.

Yet not all songs focused on how industrialism situated working class men in subjugated positions or expressed a longing for an idealized past steeped in an agrarian existence. The prevalence of the rambling theme in country music reflects the cultural significance of the railroad industry, offering, for many southerners, notions of freedom to live outside of societal constraints from the drudgery of tenant farming and the subservience enforced in the mill or factory. With railroads reaching the most remote areas of southern Appalachia by 1912, the industry required the labor of southern men and represented a mobile force, enabling one to leave or escape one’s surroundings (24). Beginning with Jimmie Rodgers’s embodiment of the singing brakeman and cowboy, Malone reveals how the rambling theme has manifested itself throughout the history of country music with explicit references to independence and masculine virility. Specifically, he demonstrates the ways in which the myths of the West have resonated in Texas swing, the aggressiveness of honky tonk, the rebellious music and lifestyles of the rockabillies and the outlaws, and the masculine swaggering of southern rock. Escapism, as it relates directly to masculinity, appears to take the form of a life outside the common restraints of society, whether that means riding a horse on the open plains, asserting an overt sexuality, or not adhering to the dictates of law. In a world where working-class men struggled through the Depression and left their farms to work in factories, the desire for autonomy has constituted musical expressions of masculinity.

While Malone delves into the complexity of white masculinity through the personas of Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, Elvis Presley, and others, he does not approach other aspects of southern culture with the same degree of detailed research and insight. Malone only briefly mentions the role that the train played in black southern culture, and states that Jimmie Rodgers’s “famous blue verses, in some cases, may have been absorbed from direct experience with black railroad workers” (127). Considering the work of Charles Wolfe on the musical interchange of black and white musicians performing the blues, Malone’s assessment of the influence of African American culture on the music and self-fashioning of Rodgers is an understatement of the complex and rich cultural exchange between black and white southerners. I do not want to give the impression that Malone omits the participation of African Americans’ music on country music. In his explanation of the national attraction to the sounds of southern string bands in the beginning of his book, for example, Malone points to how a rhythmic drive drawn from black music placed the grooves of string bands apart from other forms of rural music heard in the north (14). Malone’s investment in southern culture, however, pertains to explaining the cultural enactments of white masculinity while neglecting the full context the full context of the interwoven history of white and black southerners.1

Rod Brasfield and Minnie Pearl at the Grand Ole Opry (1940s). Photographer, Les Leverett

As Malone discusses the function of humor and delineates a narrative of comedians and comediennes from Minnie Pearl to Jeff Foxworthy, he does not thoroughly explain the cultural forces behind the prevalence of forms drawing on black minstrelsy and the country rube. Malone argues that the parodies of others and of the self—inherited from the Vaudeville tradition—served as a survival mechanism of escape from the hardships and uncertainties endured by southerners. While I had hoped that Malone would dive further into how blackface functioned in the South, I also wished he had critically assessed the performance of whiteness. In his introduction, Malone addresses the disparaging reception of the South, home to “hillbillies, white trash, rednecks,” and “hicks.” Yet, as he points to the long history of rural comedy, he mentions in passing that promoters and publicists in the industry may have only encouraged the enactments of the “hillbilly” that resonated with the general assumptions about southerners. Though the accrediting of the performance of the country rube to the role of self-parody in southern culture gives a sense of agency to the musician and comedian, Malone dismisses the complicated negotiations surrounding the self fashioning of the country musician who sought a successful career. While he points out that Hee Haw was the only viable avenue for national exposure for some of the most talented and professional musicians in the industry, he simply states that if the performers “had any significant opposition to the rube image, the feelings never surfaced” (198). Because of minimal circulation until the 1980s and the industry’s historical shaping of the constructions of whiteness, performers have negotiated a complexity of issues surrounding the perceptions of others while maintaining “authentic” identities informed by notions of southern ruralness.

Along with his discussion of the role of self parody in the function of humor, Malone finally addresses country music’s portrayal of gender. He positions the cultural need for humor as the catalyst for revitalizing the age-old theme of the “war of the sexes,” heard in the female and male duets of Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn as well as Porter Wagner and Dolly Parton (183). Malone finds this genre “one of the few phases of modern country music, at least until the late eighties, in which the woman unqualifiedly asserted her own prerogatives and challenged the supremacy of the male” (183). The “feisty” woman is an image of only modern country music, evidenced in Loretta Lynn’s “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)” (1966) which combines sexuality and amusement in a challenge to patriarchal hierarchies (184–195).

Again, in his chapter devoted to politics, Malone pointedly mentions the presence of women singers in tandem with their articulation of women’s rights. He positions the music of Loretta Lynn and Dolly Parton of the 1960s and 1970s as precursors to contemporary feminist voices. Lagging behind the second wave of feminism by at least a decade or two are such artists of the 1980s and 1990s including Kathy Mattea, the Dixie Chicks, Deanna Carter and k.d. lang (248–249). Though Malone points to the vast influence of Sara and Maybelle Carter and the omnipresence of Minnie Pearl within the industry, Malone only addresses women’s general involvement in country music in relation to a “heightened social consciousness” (248). Before the 1980s, women’s musical activities seem to be located in more pious spheres—the home and church.

As I read the introduction of Malone’s book, in which he explores his own personal relationship to country music, I am aware of an implicit gendered relationship that maps the hedonistic/piety paradox onto a male/female dichotomy. In a recollection of his youth in the rural South, Malone describes his mother singing fervently in the church while his father waited outside with the other men from the community, and drank and socialized without daring to step a foot into a place of devotion (3–4). With this frame in place, he approaches the major realms of country music through a gendered lens. In his discussion about rambling, for instance, he relegates Emma Bell Miles to the traditional sphere of piety before he launches into his explanation of the rambler as a masculine figure (122). Not only does Malone omit a feminine response to the rambler, he also does not acknowledge the manifestations of this identity as a form of female autonomy during such times as the Depression and World War II. For me, the most striking effacement is the image of the assertive cowgirl, including Patsy Montana in the 1930s, Rose Maddox in the 1940s, Patsy Cline in the 1950s, and the contemporary singer Terri Clark, who is rarely seen without her black cowgirl hat.

Yet Malone includes the masculine responses to “feminized” spheres of home and religion. For example, he expounds upon how the yearning for the symbolic home manifested during Southerners’ urban migration in the 1950s and America’s changing gender relationships during and after World War II. Eddy Arnold’s “Mommy Please Stay Home with Me” reveals a desire for a return to a supposed simpler time, in which the mother’s image ensures the sanctity of the home for her family (74). Malone does not, however, mention Kitty Wells’s replies in “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” or “I Heard The Jukebox Playing” to the misplaced anxieties—stemming from the cultural shifts of the 50s—that resulted in the accusation that women caused traditionalism’s disintegration.

Though Malone points in passing to the music of Loretta Lynn, Hazel Dickens, Dolly Parton, and Iris Dement throughout his explorations of the major realms of country music, Malone’s focus is masculinity. Malone’s gendering of the hedonistic/piety paradox eliminates the involvement of women in hedonistic realms until the 1980s and contains their earlier musical expressions in the home and church. The complicated gendered dynamics rooted in working-class southern culture cannot so easily be explained through middle-class constructions of public/private.

Despite my critical comments pertaining to race and gender, Malone’s unraveling of the tensions surrounding country music unfolds admirably in areas that have received little scholarly attention thus far. In his chapter devoted to politics, Malone offers a narrative about country music’s vast and contradictory political alignments with the labor movement of the 1930s, Farm Aid, Populism, and past presidents Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush. Likewise, he explores the centrality of dance with unprecedented research and thought. After he traces the popularity of rural dances in England and France and their immigration to America, he demonstrates the cultural role of escapism in square dancing or two-stepping and the migration of dance to urban areas through the genre of honky tonk. In response to middle-class America’s contemporary infatuation with rural life, the movements of line dancing accompanied by the sounds of “new country” have graced the images of many music videos, including Billy Ray Cyrus’s “Achy Breaky Heart,” the song that launched this singer’s ascendance to international fame. Malone brilliantly concludes that “this fusion of dance and song has taken the music into the farthest reaches of suburbia, [and] contributed to the greatest commercial growth that country music has ever experienced” (170).

Malone’s welcomed insights constitute a significant contribution to a burgeoning field of scholarship, which he was instrumental in shaping so many years ago with his Country Music, USA. In Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’, Malone makes sense of a world pulled in contradictory directions of hedonism and piety, escapism and reality, rural culture and urban life. Within the sounds of steel guitars and fiddles of honky tonk, the improvisational sonorities of Texas swing, the acoustic instrumentation of bluegrass, or the harmony singing of the Carter Family, Malone admirably juxtaposes the qualities of escapism of gospel music to the dance movements of the two-step while addressing the portrayals of work, home, reverence, and carousing. I find Malone’s astute explorations most pertinent to the music’s constructions of white masculinity in genres deemed “authentic” or, rather, those that express the desires and experiences of working-class southerners. The tensions surrounding masculinity constitute a yearning for a past autonomy, while negotiating the uncertainties of societal changes, spurred by industrialization and urbanization. Through the sounds of vulnerability and machismo, Malone presents an understanding of southern masculinity that will reverberate throughout country music scholarship.

Stephanie Vander Wel

***

Stephanie Vander Wel received her MA at the University of Virginia, where she wrote a thesis entitled “Nadia Boulanger Composer/Teacher” under the direction of Suzanne Cusick and Fred Maus. With her interest turning to popular music, she has read papers focused on Louis Armstrong, Hank Williams, Patsy Cline, and the genre of honky tonk at national and international conferences. Currently, she is a graduate student at UCLA and plans to write a dissertation about gender and country music.

***

Works Cited

Malone, Bill. Country Music, USA. 1968. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

Russell, Tony. Blacks, Whites, and Blues. New York: Stein and Day, 1970.

Wolfe, Charles. “A Lighter Shade of Blues: White Country Blues.” Nothing But the Blues. Ed., Lawrence Cohn, 233–264. New York: Abbeville Press.

- See Tony Russell’s argument about how the musical traditions of blacks and whites cannot be approached “independently of the other: the races lived too close together, and relied upon the other’s support too much for any real cultural separation” (148). ↩