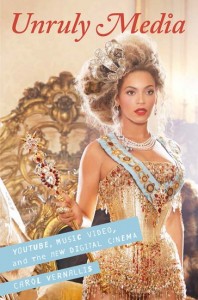

Unruly Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema. By Carol Vernallis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013 [368 p. ISBN 9780199767007 $99 (hardcover), $24.95 (paperback)]. Illustrations, bibliography, index.

{1} Carol Vernallis’ Unruly Media expands significantly on her earlier groundbreaking work in Experiencing Music Video (2004), providing a set of tools for understanding how sound and visuals work together in new kinds of media. Vernallis considers an ambitious range of media – from film, to music video, to YouTube clips – and expertly models an analytic style that captures the feeling of experiencing contemporary audio-visual media. The book is structured in three sections: the first examines digital cinema; the second, YouTube; and the third, music video.

{1} Carol Vernallis’ Unruly Media expands significantly on her earlier groundbreaking work in Experiencing Music Video (2004), providing a set of tools for understanding how sound and visuals work together in new kinds of media. Vernallis considers an ambitious range of media – from film, to music video, to YouTube clips – and expertly models an analytic style that captures the feeling of experiencing contemporary audio-visual media. The book is structured in three sections: the first examines digital cinema; the second, YouTube; and the third, music video.

{2} Part One of Unruly Media focuses on what Vernallis calls “new digital” or “post-classical” cinema: films of the 2000s that use digital production techniques and that, Vernallis argues, are strongly influenced by the audiovisual style of music video. These films use narrative approaches that differ from the classic Hollywood style. Their narratives are often elusive and sometimes hard to understand, and sound sometimes seems to animate characters and drive the action.

{3} The first two chapters of this section survey a wide range of films. In “The New Cut-Up Cinema,” Vernallis shows how films such as The Bourne Ultimatum, Day Watch, Bringing Out the Dead, and The Life Aquatic have an intense audiovisual aesthetic that borrows lighting, color, gesture, and other techniques from music video, creating fluid narrative forms that are structured by sound. The chapter that follows, “The Audiovisual Turn and Post-Classical Cinema,” is an ambitious and expansive study in which Vernallis analyzes ten fragments from different films, and demonstrates how the strategies of post-classical directors create highly intense and aesthetically stylized moments and structures that wed sound and image. Vernallis outlines the different functions of music video-like audiovisual sequences that occur in the larger context of films, including SLC Punk, Summer of Sam, 500 Days of Summer,and Tarantino’s Death Proof and Kill Bill. In other examples, Vernallis examines fragments in which music creates or suggests structure: in Run Lola Run, a looping soundtrack structures a looping narrative; in Transformers, sound, gesture, and color combine to create smooth lines out of otherwise jerky robotic movements. Finally, Vernallis explores audiovisual style now possible through post-production tweaking that shapes narrative frame, and creates color, texture, and sonic and visual lines.

{4} Of all the chapters in the book, this one best demonstrates Vernallis’ method and style; and it models a kind of analysis that mirrors contemporary experiences of media. As Vernallis points out, her choice to deal in fragments of film reflects how many viewers experience these compelling audiovisual moments: not necessarily as part of the entirety of a filmic work, but as a favorite clip, cut out of the film and posted and shared on YouTube or another platform, to be re-watched and re-mixed. Her description of these fragments is effusive and evocative, capturing the kind of sensory overload that they create. As a reader, the experience is akin to watching these clips with the assistance of an expert guide, someone accutely sensitive to sonic and visual detail and how they create meaning. On the descriptive level, Vernallis’ writing performs the ebb and flow of digital cinema. And while the media she discusses is often characterized by elusive narratives, Vernallis provides clear throughlines and structures in her chapters that make them a pleasure to read.

{5} The remaining chapters in this first section are each narrower in focus. In one, Vernallis critiques film theorists’ dismissal of music video’s stylistic influence on film, and in another explores the marriage of musical and visual elements in Bollywood film. Finally, in chapters on Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge and Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the films function as case studies for demonstrating how their directors create audiovisual-oriented forms, and use sound to suggest multiple, often contradictory, narrative arcs, themes, and perspectives. Vernallis convincingly argues that the challenging narratives of films like Eternal Sunshine, which offer multiple perspectives and uncertain conclusions, are a more truthful representation of life and relationships than the clear-cut narratives of many films.

{6} Vernallis’ second section explores the audiovisual aesthetic of YouTube clips and expands the definition of music video. In Unruly Media, a music video might be a commercially produced video that accompanies a pop song, like Psy’s “Gangam Style,” or it might be an amateur video like “Chocolate Rain,” or a surreal musical animation like “Badger Badger.” She expands the category even further, arguing that amateur video clips like “Haha Baby,” are music videos because they operationalize sound in ways that are musical. For instance, the laughter in “Haha Baby,” a home movie of a baby laughing in response to an adult, becomes a repetitive, songlike chorus, one that has invited musical remixes.

{7} In an ambitious chapter entitled “YouTube Aesthetics,” Vernallis offers a detailed taxonomy of the aesthetic effects that make clips work well on YouTube, addressing audio and visual elements of YouTube videos and common narratives and themes. According to Vernallis, the brevity of most YouTube clips results in a loose relationship to causal relations – we don’t necessarily know how or why something in a YouTube clip comes to be. In addition to outlining aesthetic features of YouTube clips, this chapter shows how YouTube offers new modes of audience engagement with media, and modes of engaging with other people through media: sharing clips, she argues, becomes a means of articulating kinship and relationships; consumers can become producers of content; and the bottomless, borderless archive of YouTube clips lets viewers drift through them, consuming them like a flaneur. YouTube is also, Vernallis argues, a space of reanimation that defies death and time: it’s a platform that enables decades-old clips to go viral, a space where users can share new videos created out of old ones.

{8} As a scholar of pre-YouTube audiovisual media—specifically, 1960s pop music and television—I found this last argument particularly compelling. One of the major modes of contact that I have with the artists that I study has been through YouTube: through clips of televised performances uploaded by fans. While YouTube is a fantastic resource for finding this otherwise hard-to-access footage, it’s an archive full of gaps, one where the sources of media aren’t well documented. The borderlessness of this archive does, however, have benefits: clips take on new life and meaning. A scene from a music variety show like Hullabaloo or Shindig becomes a standalone music video, taking on different meaning, as I share it with colleagues and students. I can add it to a playlist with videos from other periods, and see connections between their audiovisual aesthetics that might otherwise go unnoticed. Vernallis offers a tantalizing hint at the way YouTube resurrects music and media, suggesting productive avenues for future theorizing.

{9} In a later chapter, Vernallis revisits the aesthetic elements introduced in “YouTube Aesthetics” and discusses how they, and a few others, operate in the video for Beyoncé’s “Video Phone.” “Video Phone,” Vernallis argues, shows how YouTube has changed music video. Without the rules imposed by television networks, she argues, videos have become weirder, edgier, less constrained, while the growing consumption of music videos on YouTube and on mobile devices has introduced new challenges and possibilities for video directors that have resulted in stylistic changes. While Vernallis’ arguments about the changes to music video that YouTube enables are well founded, more context about how the history of how YouTube operates would have made them more convincing. In 2006, Google acquired YouTube, triggering a shift from primarily user-generated content to more professionally-generated content, and resulting in an increased emphasis on generating revenue.1 This shift raises questions about the extent to which it shaped the aesthetic of music videos on YouTube: are there new, implicit rules and restrictions in place? Or is there something about the way YouTube generates revenue that incentivizes edginess?

{10} Among the strongest and most compelling chapters in Unruly Media is “Audiovisual Change,” which examines the work that YouTube videos did during the 2008 presidential election. Vernallis’ most valuable contribution here is her illuminating discussion of how the use of visual gestures and sounds that narrate feeling creates empathetic relationships between viewers and performers. In a detailed analysis of the Obama campaign video, “Yes We Can,” Vernallis deftly shows how the sonic and visual gestures of the individuals in the video anticipate and address viewers’ emotions, a strategy used by the Obama campaign to create an affective connection between voters and the presidential candidate. My one reservation is that Vernallis’ analysis of how a video like “Yes We Can” engendered cross-cultural and cross-racial empathy sometimes seemed idealistic, and overly optimistic, given the material divisions that contribute to social inequality and racism in the United States. In addition, the audiovisual strategies that she positions as tools for working for positive social change could just as easily be deployed in propaganda of a less benevolent sort. These reservations aside, the chapter makes a crucial and important contribution to understanding how audiovisual media shape and respond to audiences’ emotional states.

{11} In the third section of Unruly Media, Vernallis tackles music video, picking up on where her groundbreaking Experiencing Music Video left off, and offering a theory of music video aesthetics for our current digital moment. The first chapter of this section tracks the shifts in music video style and approach from the 1980s to the present, not by providing a straightforward chronology of music video’s evolution, but by showing how different videos from the 1980s and the 2000s have approached different technological problems or have adopted different thematic and narrative approaches. She shows how video directors have adapted to different technological tools in ways that have shaped the degree of immediacy that videos are capable of, and argues that though today’s directors may have the ability to more finely control their videos, this may, in fact, make them seem less immediate and exciting.

{12} In the two chapters that follow, Vernallis meditates on the question of a music video canon (or lack thereof) and on the potential and challenges of applying an author-based approach to music video studies. The first of these chapters focuses on the videos of directors Dave Meyers and Francis Lawrence, and argues that each director’s approach creates very different modes of hearing songs; that the images they use adopt particular attitudes towards a song. Similar to Vernallis’ work in Experiencing Music Video, a director’s techniques are instrumental in enabling particular understandings of a song. The chapter that follows discusses the work of video directors represented in DVD collections released by Palm Pictures, and argues that the works and commentary included therein reveal that the directors think of and experience their video as art. Vernallis frames this collection as a first step towards establishing a sharable body of music video work—necessary given that, unlike film or books, music videos are rarely distributed in consumer formats. While Vernallis’ discussion of these directors’ videos provides a valuable analysis of how videos function as artworks that fundamentally shape how we hear and understand songs, I was not always convinced that the question of canonicity was vital. Vernallis does discuss the politics of canons, and their relationship to social inequality: canons often exclude work by women, and by people of color, as evidenced by the Palm DVD set, which includes no women directors; but more analysis of how a music video canon might subvert this paradigm would have strengthened the argument here. In addition, a canon- or author-focused approach risks sidelining how collaborative music videos are: they’re born of relationships between directors, musicians, and other creative staff. Vernallis is sensitive to this and alludes to this issue. In so doing, she opens up a space for future work, perhaps more ethnographic in nature, that looks at the collaborative relationships and power relationships that, in addition to the director’s vision, ultimately shape music videos.

{13} As the first study that views digital cinema, music video, and online media as genres deeply entwined with one another, Unruly Media opens up the possibilities for new research. Vernallis deftly captures the aesthetic qualities of digital media at this particular moment. The book spends some time historicizing this aesthetic but dwells largely in the present. Far from being a shortcoming, since this is a book about the contemporary culture, Vernallis creates a space to begin asking questions about how we got to this aesthetic moment. The book also provides a baseline that will prove crucial for understanding how media evolves in years to come as platforms and tastes change and adapt.

{14} In an afterward, Vernallis suggests that music videos, YouTube clips, and digital cinema provide us with tools for navigating our working lives, our relationships to other people, and our relationships to media. In a similar vein, Vernallis’ book provides valuable tools and strategies that for making sense of digital media. These tools are useful not only to scholars, but to anyone who has been moved by the sound and visuals of a film or music video, but has struggled to articulate how those effects move them.

***

Alexandra Apolloni holds a PhD in Musicology from UCLA. She is currently a Research Scholar at the UCLA Center for the Study of Women, and teaches in the UCLA Music Industry program. Her current book project explores questions of voice, race, and gender in performances by girl singers in 1960s Britain.

***

Notes

- See Jin Kim, “The institutionalization of YouTube: From user-generated content to professionally generated content,” Media, Culture, and Society, 34, no. 1 (2012): 53–67. ↩