Crossing Borders | dedicated to educators and advocates of music and museums

Each month, Echo partners with our friends at Ethnomusicology Review to bring you “Crossing Borders,” a series dedicated to trans-disciplinary music scholarship. ER Associate Editor Leen Rhee (leenrhee@ucla.edu) welcomes submissions and feedback from scholars working on music from all disciplines.

***

Dedicated to educators and advocates of music and museums

Submitted by Leen Rhee

I dedicated my Masters Thesis and Exhibit to “educators and advocates of music and museums” because I felt indebted to the museum and music educators who helped realize this project. My mentors at EMP museum and the University of Washington taught me what music education can look like, both inside and outside of the school, with or without musical instruments. And while I had many music teachers in my life (from private piano instructors, orchestra conductors, and band leaders in a Korean public middle school, to a nun in an all-girls Catholic boarding school in Kansas, a warm faculty in a New England prep school music department, and someone I consider my second mom, Arlene Cole, who was my piano teacher at Brown University), my connections with them were centered around music performance.

Performance venues, particularly concert halls, attract performers, lovers, and pundits. But the kinds of performances and spectacles that orchestras offer don’t seem to be competing so well with other options in the arts and cultural entertainment category: films, amusement parks, plain old National Parks (which I love), and aquariums, zoos, and museums. Suffice to say that some symphonies have been facing financial liquidation, while other bold and more mischievous ones began to commandeer fresh attitudes and new performance spaces. So, my idea was to invigorate concerts taking the cue from museums.

It turns out this idea was not entirely original, as I learned from a 2007 NY Times article by Lawrence Kramer titled “Concert Hall? How about Music Museum?” In it, he proposes that the classical music world embrace the success of 21st century museums. According to Kramer, museums make the visitors’ experience active and personal, while concert halls fail to do so. Museums offer a place of reflection and renewal, while the classical concert model asks for the listener’s submission. Based on these observations, Kramer suggests that symphony halls learn from enterprising art museums, which have had much success in presenting new and old art in convivial, liberal, and stimulating ways. The modern concert-museum is or should be a space of liberty and self-invention. My opinions diverge a bit from Kramer’s in regard to the types of museums he suggests that concert halls take after. Let’s face it: museums can be boring too. Some can expand our perspectives of the world, and others can be mediocre or uninviting. And while I admire the fine arts and contemporary museums that Kramer mentions in the article, I found that many children’s museums, science museums, and county art museums are better at communicating with and responding to their visitors.

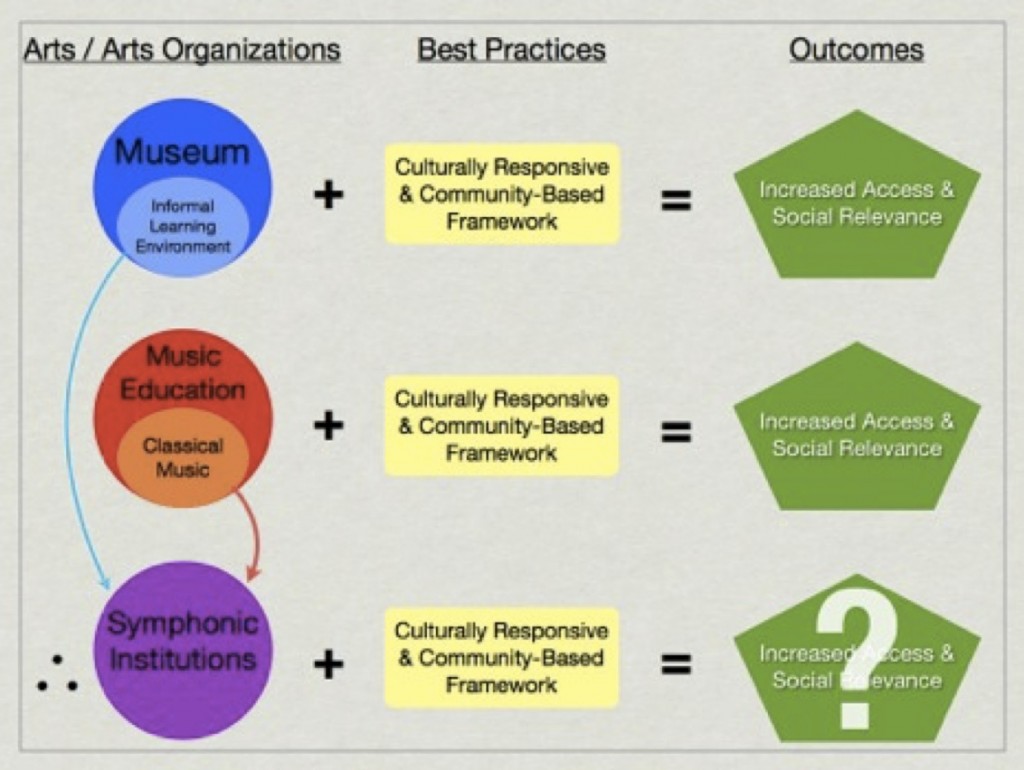

My argument was simple: If both museum professionals and music educators argue that increased access and social relevance can be achieved by applying a culturally responsive and community-based framework, why shouldn’t concert halls, or symphonic institutions, also try to experiment with new programs and methods with which to engage with their audience?

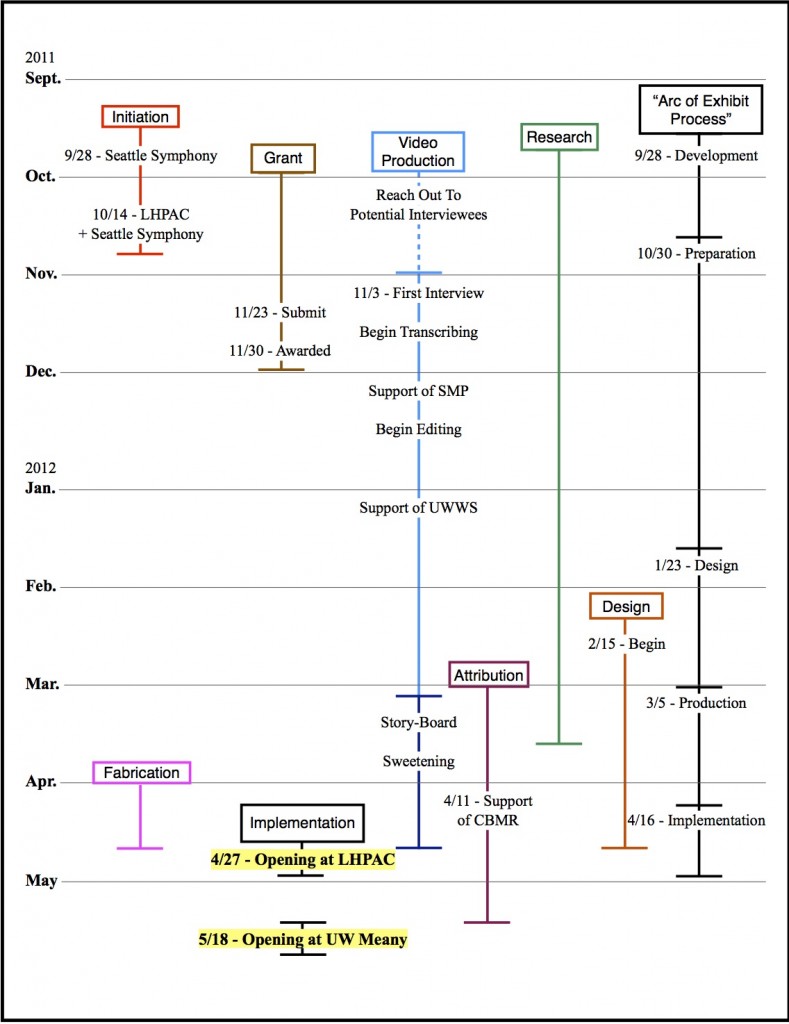

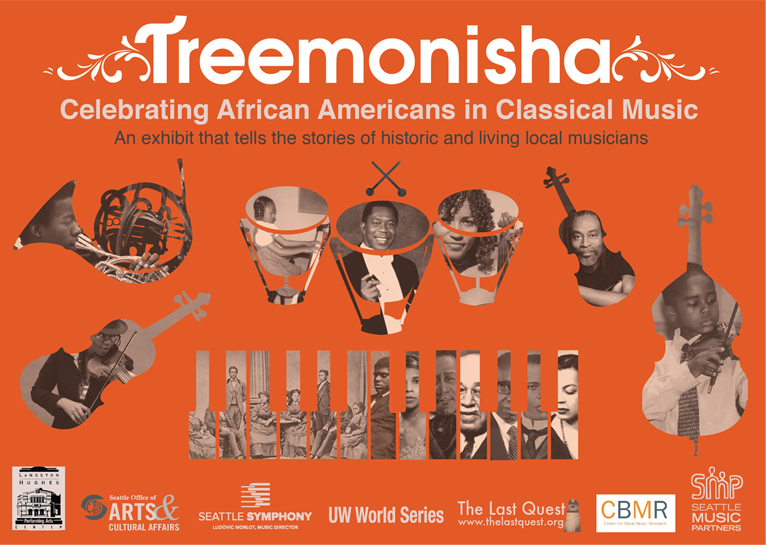

Seattle Symphony was searching for a way to appeal to the local black community. I gave a pitch to their director of education about introducing an exhibit that highlights and celebrates the achievements of under-acknowledged African-American classical musicians. Once the Seattle Symphony got involved, I began the process of soliciting resources and interviewees for the exhibit. After numerous emails, personal meetings, and eight-months’ worth of collaborative and creative work, I was able to harness a small fund from the Seattle Office of Arts & Cultural Affairs, as well as participation and accreditation from local nonprofit organizations, video producers, concert hall administrators, and the Center for Black Music Research. In the end, we managed to create a modest pop-up exhibit titled, Treemonisha.

I first came across the word “Treemonisha” while doing a quick search for famous African-American classical musicians. I gathered a moderate list of impressive but often overlooked musicians including: composer, bugler, and globe-trotter Francis “Frank” Johnson, who brought the promenade concert format to 19th century United States of America; pianist, organist, and composer Florence Beatrice Price, who witnessed the Chicago symphony orchestra premiere her Symphony in E in 1933; and Scott Joplin, who is extolled for his prolific output in ragtime music, but less recognized for his contributions to opera. Joplin died without witnessing a full staging of his opera, Treemonisha. Treemonisha became the title of my exhibit.

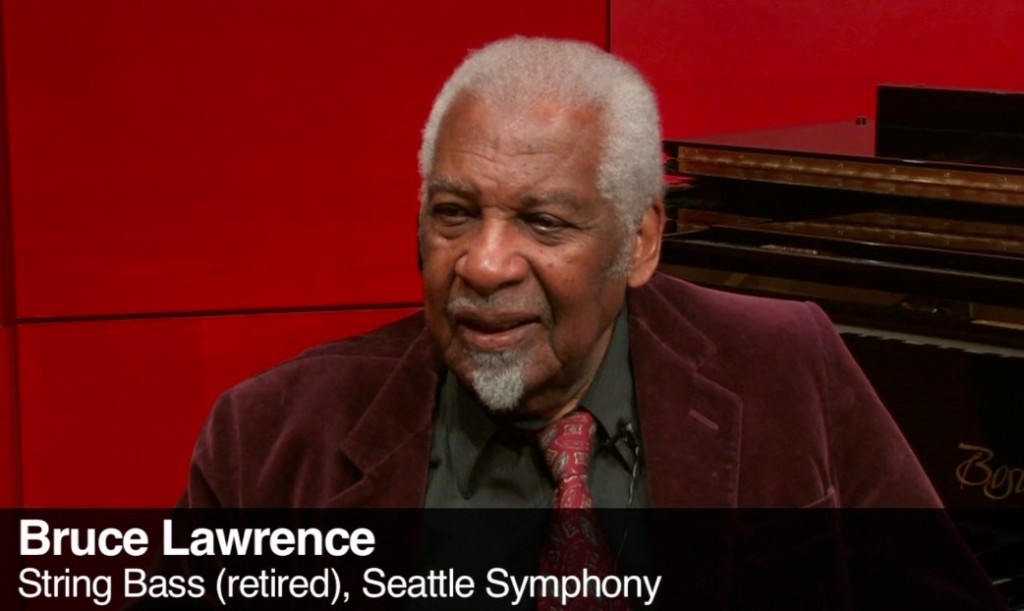

Treemonisha had panels featuring historic musicians, as well as iPads playing short themed interviews of local students, music teachers, and performers. The exhibit was installed in conjunction with two concert events—one at the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center, and the other at University of Washington’s Meany Hall for the Performing Arts.

[Bruce + MASQ + panel display + visitors 1 + Visitors 2]

When I was defending my Masters Thesis, my advisor asked what I had learned from this experience. While searching for an appropriate answer to this question, I took the longest pause I have ever made in a formal conversation.

What I learned was that ideas, conversations, and the physical presence of educators and advocates matter because without the threads and bonds that have been formulating even before I got to Seattle, I would not have been able to find the networks of support that were essential to the creation of the exhibit. I cannot, nor do I wish to, claim that Treemonisha (the exhibit) changed the lives of black Seattlelites and Pacific Northwesterners pursing a career in classical music. The best I can say is that we created a nodule in the larger narrative of fighting injustice through education. I did not find answers to why social, economic, and cultural barriers persist for certain racial and ethnic groups, but I did come away with humble realizations and, frankly, more questions.

I also learned that there is a glaringly wide crack between the borders of ethnomusicology and musicology when it comes to the study of African American, or for that matter, Latin American and Asian American classical musicians. The ethnicities point to ethnomusicology but the word “classical” points to musicology. How this will pan out in the future depends on how students and emerging scholars approach and champion their research. Many of my colleagues seem to be in similar situations, so I will let their work speak for themselves and return to museology for now.

museology musicology, musicology museology

In museology, the imperative is: always evaluate. We evaluate the heck out of our visitors in the hopes of making their museum experience better next time. And in order to evaluate, we try to formulate questions about their habits, needs, and interests. This may be why I liked studying museum education. Educators and advocates working in mission-driven organizations untiringly strive to realize their vision. I want to dialogue with them to conceive of and articulate productive questions. I want to ask them how to maintain and enact hope.

In closing, I channel what Angela Davis said in her momentous return to UCLA last year. In response to a question about how to activate hope, she alluded to Kant’s concept of the categorical imperative and replied that (and I paraphrase here) we have to keep asking questions to better express and comprehend society’s injustices. We have to be prepared for the conjunctures in life that can and do bring about change. We have to act as if it were possible to change the world. And to this, museum professionals will add: one visitor at a time.