Crossing Borders | Cultural Revolutions: A Study in Contrasts

Each month, Echo partners with our friends at Ethnomusicology Review to bring you “Crossing Borders,” a series dedicated to trans-disciplinary music scholarship. ER Associate Editor Leen Rhee (leenrhee@ucla.edu) welcomes submissions and feedback from scholars working on music from all disciplines.

***

This month, our contributor is Nancy Jakubowski. Nancy holds a BFA in Illustration from the Rhode Island School of Design (Class of 1984) and has worked at the Brown University Library since 1991. She splits her time between the Gifts Department of the Rockefeller Library, and the Orwig Music Library, where she is a Senior Library Specialist. I am pleased to have her featured in Crossing Borders, and welcome other librarians, archivists, designers, and researchers to contribute to this section of Ethnomusicology Review.

***

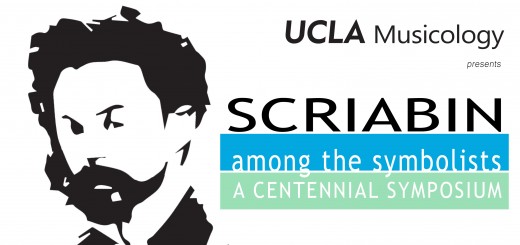

Cultural Revolutions: A Study in Contrasts

Submitted by Nancy Jakubowski

The idea to do an exhibit on the Chinese Cultural Revolution was inspired by some uncatalogued records tucked away in our Music Library. The collection was a mix of recordings from across Asia. The visual contrast between them was striking – red album covers with men and women dressed alike, posing heroically versus sleeves sporting groovy graphics, bouffant hairdos and miniskirts. The social disparities behind the kitschy iconography, however, were even more extreme.

Image 1. Photo of exhibit case

The 1960s and ’70s were turbulent decades. Post-WWII prosperity morphed into discontent with the status quo. Youthful idealism fueled political protests in the United States and around the world. China was no exception to this period of unrest and 1966 ushered in an era known as “The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” aka “The Cultural Revolution,” a decade of brutal repression, terror and atrocities visited upon the populace. Radical political and social changes were orchestrated by Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party, as part of a long-term strategy to transform the “People’s Republic” into a Communist utopia. The process began with Mao’s ascent to power in 1949, through the failed “Great Leap Forward,” a plan to rapidly industrialize the largely agrarian economy, which resulted in the deaths of millions through famine, purges, executions, forced labor, imprisonment and torture. Ostensibly the Cultural Revolution that followed was about rooting out “the four olds” – outdated ideas, customs, culture, and habits – but the reality was far from innocuous. Political leaders manipulated a budding student movement, the Red Guards, into helping cleanse the country of perceived threats from intellectuals, Capitalists, and anyone else deemed dangerous to the Communist ideology. People were not the only targets of this campaign – “questionable” art and cultural objects were sought out and destroyed, including sheet music, records, and musical instruments. Ironically, after a short time, the Guards themselves were seen as a threat to order and put down. Unfortunately, repression, intimidation, violence, and killings sanctioned by the State continued against the population. Musicians, artists and other creative professionals, or “Cultural Workers,” had to conform or risk punishment, and many suffered under a regime that co-opted the arts for political ends.

Image 2. Photo of Chinese Opera Recordings and Librettos

Music was an important means of propaganda and political agitation even before the Cultural Revolution. Mao felt that art, music and literature should be used to educate workers, peasants and the army, so composers and artists were urged to go out amongst the people for inspiration. In 1956, Mao even drafted a talk to “Music Workers,” which cautioned against letting Western influences and training compromise Chinese culture. Music in service of the State goes back even further in Chinese history however, with Confucius espousing the notion of “good music” being necessary for a stable society.

During Mao’s reign, music was used to promote his rule and to support the aims of the Revolution and the Communist Party. However, due to a shortage of professional musicians, peasants, students and others received basic songwriting training in order to churn out tunes for the cause. Along with subjects celebrating the Revolution, the Red Army, etc., Mao’s own writings and poems were set to music and known as “yuluge.” The English titles of many of these pieces seem stilted, and in some cases, inadvertently humorous, with their heroic language and revolutionary fervor, but these albums represent a frightening reality – they contained some of the only sanctioned entertainment available to a populace of over 800 million people during the decade of the Cultural Revolution.

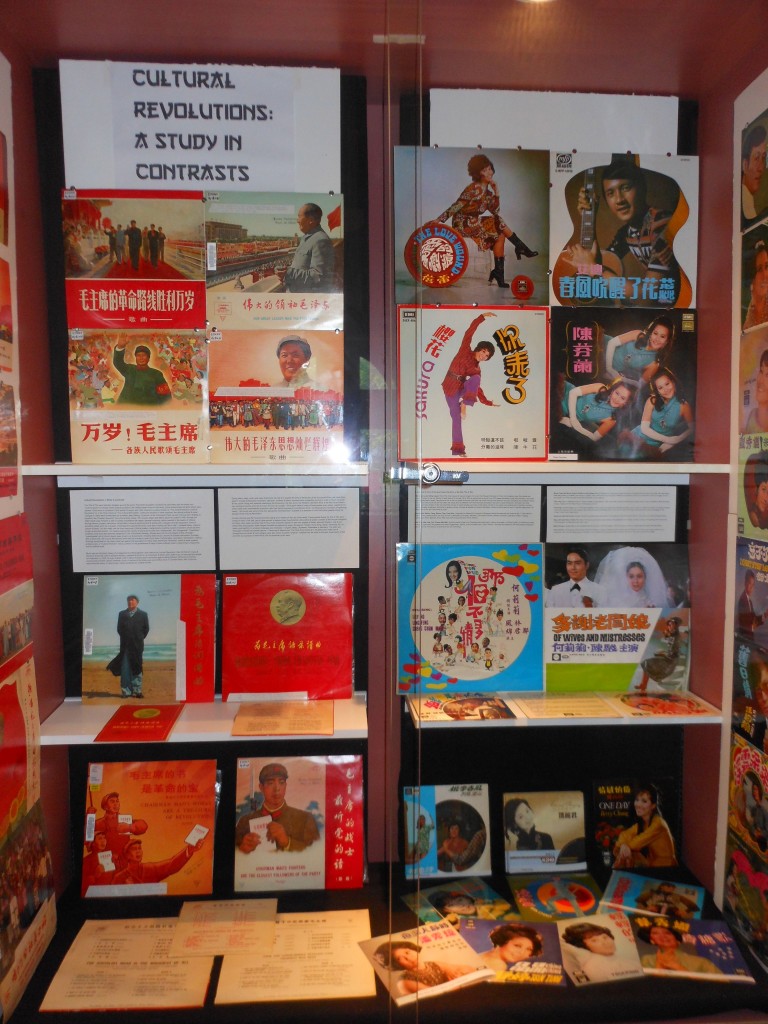

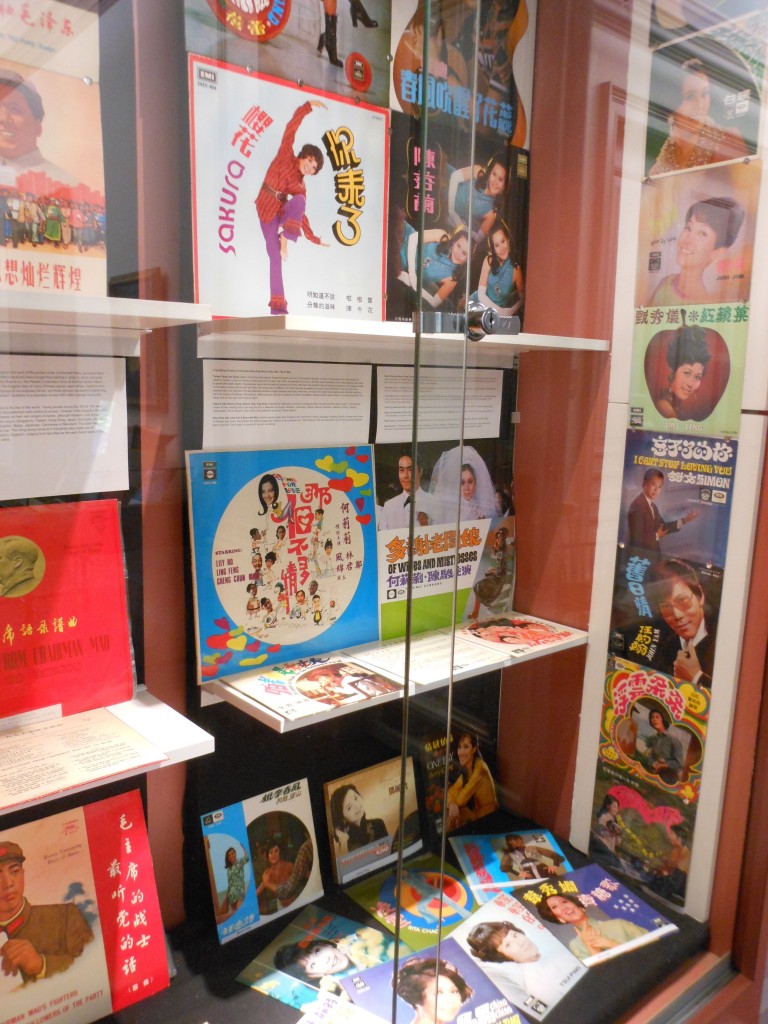

In stark contrast was the musical revolution going on in the US and the rest of the world. Young people were turning to rock ‘n roll, folk, jazz and other genres to express their dissatisfaction with politics and society. Many Asian countries developed thriving music industries based on their own talent, although Western rock and pop artists were also popular. Asian singers traveled throughout the region and many performed in multiple languages, including English, Malay, Japanese, Cantonese, and Mandarin. The latter two evolved into specific genres – Canto-pop and Mando-pop. The Hong Kong movie and TV business also made use of homegrown pop music and many singers also worked as actors.

Image 3. Photo of Asian pop records

One of the most beloved vocalists in Asia, as well as in the People’s Republic of China, was Teresa Teng (aka Deng Lijun). She started out in Taiwan in the mid ‘60s but her career really took off in the late ‘70s. As restrictions on music in the PRC eased somewhat under Deng Xiaoping (who came to power after Mao’s death), Teng was one of the first artists to become a hit there. Her music was banned briefly for being too bourgeois, but it stayed a staple on the black market until the ban was lifted. She was as well known as China’s new leader, whose surname she shared. A popular saying was “Old Deng rules by day and Little Deng by night.” Below is a video of one of Teresa Teng’s most famous songs, “The Moon Represents My Heart.”

Aside from Chairman Mao, the person with the most impact on music during this period was his third wife, Jiang Qing. She had been an actress with very little musical training but in her new role as head of the Ministry of Culture, she launched an ambitious scheme to remake Peking opera. Under her direction, eight “model revolutionary theatrical works” were developed, although all were reworkings of existing pieces. Ten more “model” works were created by the end of the decade. Gone were the “emperors, kings, generals and ministers, scholars, and beauties” from traditional Chinese opera. Instead, heroes would be heroes (of the Revolution, of course – workers, peasants, and soldiers) and the villains could be any one of a cast of characters targeted by the Communist Party – landlords, Capitalists, the Japanese, Kuomintang “bandits”, etc. Surprisingly though, Western instruments were not banned completely – Madame Mao thought they made opera sound more heroic and even Mao had condoned them in his writings. However, there were some restrictions – no tubas, trombones or bassoons (!), and percussion instruments were muted – and of course, no Western compositions could be performed. These “model” pieces, especially the original eight, became the only approved musical entertainment aside from the revolutionary songs and yuluge settings. They appeared on stage, radio, tv, and in the movies. Traveling companies performed them throughout the country, with the same scripts, costumes, and sets for every production. Even today, people of a certain age can sing the songs by heart, whether they wanted to learn them originally or not, since that was all anyone heard or saw performed for a decade. In an era when we can access practically any piece of music with the click of a mouse, such a limited sonic landscape, especially one that lasted ten years, is unimaginable! According to a New York Times article from 2000, some model operas were still being performed across China, evoking nostalgia in their audiences but distaste in the minds of others, appalled that these works were still popular, despite their dark history.

Unfortunately, repressive regimes around the world still try to erase history by destroying cultural objects – the giant Buddhas in Afghanistan and museum objects in Mosul are recent examples, and music is still used to manipulate, e.g. the “hate” songs of the Rwandan genocide and white power music in Nordic countries. However, as current events have shown, what distinguishes freedom of expression from a tool of oppression can be open to interpretation. That the arts are a powerful means of expression is undeniable.

***

Nancy Jakubowski holds a BFA in Illustration from the Rhode Island School of Design (Class of 1984) and has worked at the Brown University Library since 1991. She splits her time between the Gifts Department of the Rockefeller Library, and the Orwig Music Library, where she is a Senior Library Specialist.