The Sounds of Transgressive Geographies

Greg Blair, PhD, Associate Professor of Art Northern State University

It’s not a matter of emancipating truth from every system of power… but of detaching the power of truth from the forms of hegemony, social, economic and cultural, within which it operates at the present time. – Michel Foucault

In early 2012, when members of the punk band Pussy Riot created a performance of protest in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, they generated a gripping and raw insurgency rooted in spatial transgression that sent shockwaves through the global community and initiated an inter-global discourse about feminism, religion, Russian politics, incarceration, corruption, orthodoxy, and the current state of punk rock music in one fell swoop. As one of Pussy Riot’s defense attorney’s, Nikolay Polozov, declared at their trial, “There’s probably not a corner of the world that doesn’t know what the group Pussy Riot is.”1 And although their actions stand as a powerful attempt to subvert hegemonic power using a fusion of music and spatial transgression, this does not mark the first time that place, mobility, and sound have effectively been brought together as a practice of political transgression. In many ways, the experience of music has always been infused with aspects of space and mobility. As Georgina Born has noted, one of the “most important distinguishing feature of auditory experience… [is] its capacity to reconfigure space.”2 Music also has an intrinsic mobility, described by Owen Chapman in these terms: “Sounds travel through networks, memories, between people and places, from performers to audiences, through time as much as space, both live and as sonic potential stored in mechanical and electronic recordings, digital files and musical instruments. Sound is constantly on the move.”3

In addition to the confluences between music, mobility, and spatiality just mentioned, there has also been, in many ways, a sort of contrived territorialization in the distribution and consumption of music. “Genres” or “scenes” are presented and constructed as collective identities that encompass styles of clothing and personal appearance, socio-economic status, and political platforms. These “genres” or “scenes” sometimes have the feel of fortified encampments—distinguishing and protecting themselves from the infiltration of outsiders. However, as Simon Frith has pointed out, “genres” as spatialized compartments are highly problematic. As Frith asserts in his “Genre Rules,” the “use of genre categories [has been] to organize the sales process (Frith’s italics).”4 The mapping and delineation of genres is also exceedingly fluid depending upon context and intended market. Another problematic issue of “genres” is that certain music simultaneously fits into more than one existing genre label. Other than providing a taxonomy for the spatial organization of your local record store, the relation between space, mobility, and music in terms of “genre” is limited. Will Straw makes a similar claim about the perceived hermetic borders of musical “scenes” as spatialized compartments. Straw argues that the “diversity of musical practices unfolding within particular urban centers,” undermines “claims as to the uniformity of local music culture.”5 He also reminds us that a seemingly removed and remote “scene” can still be “shaped by economic or institutional globalization.”6

The reason I draw attention to the lack or absence of clear boundaries in musical “genres” or “scenes” is to question the notion of transgression that is often attributed to musical “genre-benders.” For as long as musical “genres” have existed, there have been those who have been perceived as breaking down the walls separating each “genre” as they head out into new musical territories. Indeed, genre-benders (or breakers) have been around for as long as “genres” themselves, stretching back to the beginnings of music history. As Roy Shuker has written however, “no style is totally independent of those that have preceded it, and musicians borrow elements from existing styles and incorporate them into new forms.”7 Throughout the history of music, genre-bending musicians have often been celebrated as being innovative and revolutionary. And in certain instances this may be true: Bach’s combination of religious music and secular theater was trailblazing, and so was Bob Dylan’s mixture of folk and rock on Bringing It All Back Home (1965). Miles Davis’ fusion of jazz and rock on In A Silent Way (1969), and Beck Hansen’s genre-hopping albums Mellow Gold (1994) and Odelay (1996) have also been considered important musical innovations. However, from what we know from Frith and Straw, the spatial trangressiveness of these efforts may not be so radical. They may not even be transgressive in the etymological sense of “stepping over” and breaking through an established boundary.

Having established this distinction, I want to address another form of spatial transgression that has occurred in music that is explicitly more spatial, mobile, and political in the disruption of dominant powers and the recognized social order. This article will explore the concept of transgressive spatiality as generated in three different forms: musical consciousness, musical works, and musical performances. It is here that I turn our attention towards a few specific examples of musicians who have created a spatial performance of transgression through sound. I am referring to particular musical projects that have actively utilized spatial strategies to critique and resist dominant power formations and cultural norms. These instances utilize place-based tactics to develop transgressive geographies and form a genealogy in the history of music connected not through genres, context, or musical composition, but by a commonality of procedure and method. This article is an analysis of what political spaces of resistance can sound like—as the sounds of transgressive geographies.

There are a considerable number of musicians that have displayed, at certain times, spatial tendencies in their music (Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henry Brant, Luigi Nono, Woody Guthrie, Alvin Lucier, Black Flag, Pink Floyd, Efterklang). However, I have chosen specific musical projects by Sun Ra, Joni Mitchell, and Pussy Riot, because of how they create a “breach in the pop milieu, in the screen of received cultural assumptions” through a topological praxis.8 These projects are political acts executed through music, hinged upon a certain ungrounding and transgression. There is a radical air to these transgressions—a dissatisfied proclamation, an assertive desire for transformation—or what Foucault might call a new “discourse that combines the fervor of knowledge,” with the “determination to change.”9

But what is meant by “dominant power formations and cultural norms” and how is music well suited to resist and question their legitimacy? In a general sense, I am pulling from the tradition of Practice theory as begun by Pierre Bourdieu and extended by Foucault and others. The notion of resisting the imposition of general cultural schemas or formations comes from Bourdieu’s concept of “habitus” in which the “permanent internalization of the social order in the human body” is counteracted by the “human ability to act upon and change the world.”10 I am also drawing upon Foucault’s critique of how ideology and thought “operate upon the entities of our world, to put them in order, divide them in classes, group by name.”11 As will be detailed below, these musicians apply mobility and music as a strategy and “refusal to be fixed or pinned down.”12 Within this refusal is a turn towards agency enacted in the world.

In Giorgio Agamben’s analysis of Foucauldian apparatuses, he identifies and investigates the apparatus’ effects on the subject, as anything that captures, restricts, or determines the thoughts and actions of living beings. Agamben also advocates finding new ways to dismantle them through individual agency, and points out “this problem [of reclaiming the subjective power of an apparatus] cannot be properly raised as long as those who are concerned with it are unable to intervene in their own process of subjectification.”13 The sounds of transgressive geographies are the attempts by these musicians to affect change—refusing to be imposed upon and resisting being fixed and bounded in place.

Yet, one might ask: why music? What does music do in terms of spatial transgression that is not achieved or is not as well performed through other modes of creative expression? How does music enable and accentuate the mobility and spatiality needed for transgression? Music aids in the production of a spatial transgression because there are inherent spatial and mobile qualities to music—beyond the physical facticity of how sound waves transfer energy to move the body on a molecular level, music also “creates and constructs” a spatial and mobile experience.14 The experience of music is unique because it is a multivalent bombardment of the senses – visual, haptic, aural, and aromatic – that creates an embodied engagement. This embodied immersion isn’t just a “way of expressing ideas, it is a way of living them,”15 and as such, “the experience of music… gives us a way of being in the world.”16 Music provides both the performer and the listener with an opportunity to perform transgression, to live out a spatial transgression through performance. The absorption in the material physicality of sound is often also accompanied by critical reflection, what Jane K. Cowan suggests as a “double sense of engrossment and reflexivity.”17 In terms of opening a possibility for spatial transgression, Frith gives this account of the inimitable spatiality and mobility of music: “Music is thus the cultural form best able both to cross borders – sounds carry across fences and walls and oceans, across classes, races and nations – and to define places; in clubs, scenes, and raves, listening on headphones, radio and in the concert hall, we are only where the music takes us.”18 Music has this ability to move us, to take us into new territories, whether through a shift in consciousness, on a narrated journey, in a psychic projection, or by creating a performance in a particular place. Music provides a powerful vehicle for the resistance of the established social order through the performative invocation of a transgressive geography.

Sun Ra – Space is the Place

In 1965, Eric Burdon and The Animals released Animal Tracks, which included their hit single “We Gotta Get Out Of This Place.” Although it was embraced as an incisive summation of the alienation and malaise that many young people felt in the middle of the 1960s, especially American troops stationed in South Vietnam, it also plays as a synecdoche of the thinking and spatial strategies adopted by Sun Ra and his Interstellar Arkestra from almost five years earlier.

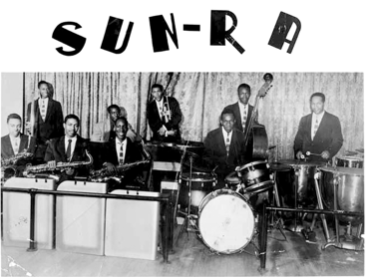

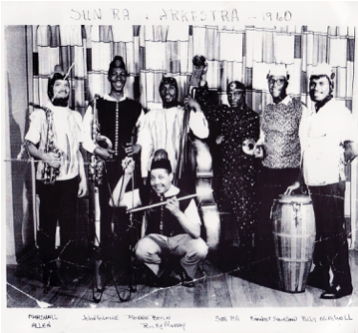

Beginning around 1960, Sun Ra (Le Sony’r Ra) began a personal and musical transformation which took him and his band mates from being traditional Big Band Swing musicians (Fig.1) to space travelers (Fig.2). Sun Ra’s “spatial turn” is a marked shift in his philosophy and music that began at this time. Prompted by frustration with the representation of African-American identity and consciousness in American and European culture, Sun Ra decided to “leave” Earth for the liberation of space. Through his experience of the vibrant political activism in Chicago in the 1950s, Sun Ra began to consider the Western/European version of African history as a discursive and systemic means of oppression. In 1952, he legally changed his name to Le Sonny’r Ra, and considered his birth name (Herman Poole Blount) to be a slave name.

The myth of Sun Ra’s inspiration for space travel is ambiguous and fragmented, only becoming indelible through reiteration and self-perpetuation.

Fig.1 Sun Ra and the Arkestra, 1956. Image courtesy of listenrecovery.wordpress.com. Accessed 11/12/15.

Fig.2 Sun Ra and the Arkestra, 1960. Image courtesy of listenrecovery.wordpress.com/category/sun-ra/ Accessed 11/12/15.

What is known about his inspiration for space travel is that at some point in time (the exact date is unknown – perhaps 1936 or as late as 1952), during religious meditation, Sun Ra traveled to Saturn and was told by alien beings that “when it looked like the world was going into complete chaos, when there was no hope for nothing, then I could speak, but not until then. I would speak, and the world would listen. That’s what they told me. Next thing, I found myself back on planet Earth.”19 This event precipitated the beginning of the travels to space. In 1960, Sun Ra and the Arkestra recorded Interstellar Low Ways, which marked the first album that fully embraced space travel. This was also about the same time that Sun Ra and the Arkestra began dressing for space. John Szwed writes that “When the Arkestra was booked into the Wonder Inn… for five nights a week, Abraham bought them an old wardrobe from an opera company, one heavily stocked with capes, puffed sleeves, and doublets, and then they began to dress for ‘space.’”20

“Travelling” to space became a spatial transgression of the dominant ideology and power formations by stepping outside of their reach. To be out-of-place was a means to spatialize the earth-bound forms of power and ideology. For Sun Ra, the efficacy of going to space rested “in its ability to reveal topographies of power” that were part of their earthly being.21 “Space” for Sun Ra was a place in which, he, his Arkestra, and his listeners, were not left out of culture, but instead could be active producers of culture. “We’re like space warriors,” asserted Sun Ra, “Music can be used as a weapon, as energy. The right note or chord can transport you into space using music and energy flow. And the listeners can travel along with you.”22 For Sun Ra, space did not yet have a history – it was still being written. Going to space was a means to transgress the limitations of Earthly existence. To be out-of-place was an opportunity for the creative invention of another way of being. This was especially true for African-American identity and consciousness. Sun Ra described the relationship between African-American consciousness and the travels to space when he claimed that:

in those days I tried to make the black people, the so-called Negroes, conscious of the fact that they live in a changing world. And because I thought that they were left out of everything culturally, that nobody had thought about bringing them in contact with the culture, none of the black leaders did that… that’s why I thought I could make it clear to them that there are other things outside their closed environment.23

Even though there was not a physical spatial transgression, the space costumes and the performance of the music by real living bodies, sweating and swaying to the rhythms, provided a materiality to the transgression which bridged the physical and the symbolic. Going to space through music became a performative critique of power that revealed the emancipatory potency of transgression. In this way, Sun Ra’s mission grew from the liberation of African-American consciousness to the liberation of those oppressed by all forms of hegemonic power. “At one time I felt that the white people were to blame for everything, but then I found out they’re just puppets and pawns of some greater force, which has been using them… Some force is having a good time off both of them, and looking, enjoying itself in a reserved seat, wondering, ‘I wonder when they’re going to wake up.’”24 Sun Ra’s attempts to “wake people up” took the form of a transgressive geography by removing the listener from Earth-bound power structures in order to have a new geographical perspective. Similar to the overview effect experienced by many astronauts in seeing Earth from outer space, Sun Ra asks his listeners to recalibrate their consciousness – to adjust the focus of their view – to examine and question the social orders of Earth from afar. This perspective opened the space traveler to the possibility of a subversive deconstruction of the forces that were impinging upon them. Getting out-of-place— transgressing geographies—enabled Sun Ra and his listeners to then get back-into-place, to come back to Earth reinvigorated, with a new consciousness and empowerment. This sense of liberated thought in the experience of Sun Ra’s spatial transgression is neatly summarized in one of his poems entitled The Potential:

Beyond other thoughts and other worlds

Are the things that seem not to be

And yet are.

How impossible is the impossible

Yet the impossible is a thought

And every thought is real

An idea, a flash of intuition’s fire

A seed of fire that can bring to be

The reality of itself.

Beyond other thought and other worlds

Are the potentials…

That hidden circumstance and pretentious chance

Cannot control.25

Yet, perhaps the experience of spatial transgression and enlightened consciousness elicited through Sun Ra’s performance is best illustrated in the words of those who witnessed him performing. The jazz musician, Idris Ackamoor, recalls seeing Sun Ra and his Arkestra for the first time at the 1971 UC Berkeley Jazz Festival with these words:

The evening was a transformative experience. The melodic sounds… the otherworldly sounds… the cacophonous sounds fed my soul and spirit. It was like a musical three-ringed circus on the planet Venus with Sun Ra being the ring master conducting the proceedings with a wave of his hand, the bend of a finger, the movement of his cape as John Gilmore unleashed a sonorous gut wrenching barrage of cascading notes. Marshall Allen playing his alto like a golden serpent that had to be stroked… flailing his fingers across the scales and coaxing unheard of sounds… screeches… howls… human cries of unmitigated freedom and expression… I was transformed by the theatricality of the Arkestra and that night will always be seared in my primary memory as an epiphany in my musical development.26

Sun Ra’s music and performances serve as examples of a musician using transgressive geographies to transform the consciousness of his listeners. However, this is only one method of musical spatial transgression. Other musicians have created effective spatial transgressions using alternate strategies, including a symbolic journey taken over the course of a musical work—presented as a sort of travelogue—such as Joni Mitchell’s 1976 album Hejira.

Joni Mitchell – Hejira

In his review for the New York Times of Joni Mitchell’s Hejira, John Rockwell wrote that the album is “full of narrative bits more or less fictionalized from her travels that are interwoven with broader intimations.”27 However, Rockwell never really fully identifies what these intimations might be. I would suggest that one of these broader intimations is Mitchell’s spatial transgression through the use of sound—an attempt to remain out-of-place as a method to shed cultural impositions, by never being static—remaining uncurbed by, and insubordinate to, cultural expectations.

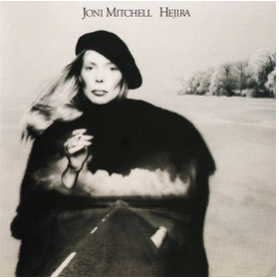

The implications and celebration of movement, of remaining out-of-place, are entwined throughout the entire album and are explicitly expressed in the album title. Hejira translates as “journey” and refers to Muhammad’s flight from Mecca to Medina after hearing of a possible assassination plot. Written while driving alone from Maine to California, not only do the lyrics of Hejira convey the power of a journey, but also the rolling momentum of the music itself is as “unceasing and hypnotic as the freeways Mitchell describes in her songs.”28 Jessica Hopper comments that the songs are “long and lovely, burbling and unspooling.”29 The musical composition of the songs emphasizes the sense of endlessness and freedom on the road—the sensations of being unrestrained, unchecked, and non foreclosed. The constant state of motion is part of Mitchell’s spatial transgression because of its unfixed and unbounded nature. The cover of the album features a grainy image of an open highway dissolving at its edges into the background (Fig.3). The repeated reference to the open road in the album and lyrics recall Jean Baudrillard’s description of the liberation associated with a “spatial, mobile conception” of freedom as being unencumbered by “historical centrality.”30 Similarly, Mitchell’s continued transgressions and movements through place form a spatial and mobile conception of freedom and a concerted effort to deny the foreclosure of being by cultural gender norms.

Fig.3 Album cover for Hejira, released in 1976. Image courtesy of jonimitchell.com. Accessed 11/12/15.

Mitchell’s rambling journey across America flies in the face of the gender politics and cultural norms of the post-war 1950s image of the American housewife whose existence and identity was fettered to the home, the domestic space, and familial responsibilities—along with the accompanying prescription of gender roles, body politics, and normativity. It is from these types of cultural impositions that Mitchell’s transgression arises. She does not exist where she is “supposed” to be, and is therefore “out-of-place.” Ariel Swartley writes that it is out on the road where Mitchell finds that the “confines of civilization can be momentarily forgotten.”31 However, I think we can read Mitchell’s actions as more than mere escapism, more than a momentary escape. Mitchell’s journey is a conscious attempt (she could have easily flown from Maine to California) to gain critical distance from certain power structures through the use of spatial transgression. This distancing is not to imply an absolute detachment from the burden of power dictates. As Michael Walzer claims, “criticism does not require us to step back from society as a whole but only to step away from certain sorts of power relationships within society. It is not connection but authority and domination from which we must distance ourselves.”32 Mitchell certainly does not attempt to escape from society as a whole (Hejira is a pop music album meant for commercial distribution after all) but rather endeavors to more fully engage with the power relationships of body politics and gender roles through a mobile spatial critique.

To transgress an existing boundary also means to reify that boundary – bringing to light its oft-imperceptible existence. Mitchell accomplishes this, not just on Hejira, but also throughout many of her songs and albums by using a spatial transgression of being out-of-place. As Hopper writes, the song Blonde in the Bleachers, from Mitchell’s 1972 album, For the Roses, is “one of the best songs ever written about the rules and (gender) roles of the road.”33 Yet, it is with Hejira that Mitchell develops this critique with the most force, casting doubt on the placedness of gender, throwing into question its relevance, authority, and position. Hopper writes “Hejira is one of the most feminist albums ever.”34 Swartley writes that Hejira points to the “long-taught myth that a woman should make a total commitment to love and the hard-won discovery that a career may require the same consuming passion.”35

Throughout her transgression, Mitchell is also careful not to offer any “glib conclusions.”36 She does not provide answers as to how gender roles and body politics need to change, but emphasizes that some type of change is needed. Mitchell’s spatial transgression is of a piece with Foucault’s sense of practicing theory: “This is a struggle against power” writes Foucault, “a struggle aimed at revealing and undermining power where it is most invisible and insidious.”37 For Mitchell, cultural myths and inscriptions have been used as a form of repression for too long.38 Through the spatial transgressions of Hejira, Mitchell creates a counter-discourse to the prevailing one, a discourse that reflects Mitchell’s own search, one that is uncertain, ambivalent, isolated, empowered, frightened, and independent. As Swartley comments, “that is what Hejira is about: it is not the answers that are most important but the search itself.”39 An important part of this search is to reveal and question the dispersion of power in the gendering of space.

Even if the music of Hejira is not heard as being transgressive or does not instill a sense of mobility on the open road, and instead comes across as conventional for some listeners, Mitchell’s lyrics certainly assert her exploration of spatial transgression over the course of the album. Nearly every song makes references to travel, roads, mobility, and freedom. For example, in Refuge of the Road, Mitchell’s indicates the unease of exploring nonconformity when she sings, “And it made most people nervous, They just didn’t want to know, What I was seeing in the refuge of the roads.” In the song, Amelia, which finds inspiration in the spatial transgressions of Amelia Earhart—the first woman to fly across the Atlantic and a forceful advocate for the presence of women in the male dominated world of aviation—Mitchell parallels Earhart’s motivation for travel with her own when she sings, “People will tell you where they’ve gone, They’ll tell you where to go, But till you get there yourself you never really know.” Perhaps the most explicit sense of Mitchell’s mobility as a critique of established gender norms, arises in the lyrics of Song for Sharon, where Mitchell establishes a dichotomy between herself and another woman. The other woman, Sharon, is fixed and bound in place, whereas Mitchell has mobility and the refuge of the roads:

Sharon you’ve got a husband

And a family and a farm

I’ve got the apple of temptation

And a diamond snake around my arm

But you still have your music

And I’ve still got my eyes on the land and the sky

You sing for your friends and your family

I’ll walk green pastures by and by

Interestingly, Mitchell does not cast judgment on Sharon and even hints at a twinge of longing for the certainty of her life, but in the ends remains as a traveler and transgressor, steadfast in her search for something more than the gender roles imposed upon her by society. The lyrics mentioned here, along with the rolling melodies of the music, are not meant to transport the listener onto a journey the same way that Sun Ra intended, but rather present one woman’s exploration and defiance of the gendered ordering of space as it existed in her contemporary existence.

A Pack of Bitches from the Sexist Regime – Pussy Riot

Even though the questioning of the gendering of space in Mitchell’s critique creates a tidy link to the performance of “Punk Prayer” by the members of Pussy Riot, the methodology used by each to critique the gendering of space is also quite distinct. Whereas Mitchell assertively attempted to stay “out-of-place,” Pussy Riot’s performance was an attempt to “get-into-place.” Each of the musicians employs a different modality (music as a work and music as performance) of spatial transgression, while still generating a resistance to the established social order.

Much of the backlash in Russian society against Pussy Riot’s performance was indeed because of the “getting-into-place” methodology through which their spatial transgression was enacted. The fallout of the Pussy Riot performance amongst the various levels of Russian authorities and some media outlets centered around the rhetoric of the sacred and the profane to incite an indictment of Pussy Riot’s actions as “hatred and enmity of religion and hatred of Orthodox Christians.”40 These attacks were misguided however, since the intentions of Pussy Riot’s spatial transgression was not grounded in a platform of religious hatred, but in the distribution of power and the gendering of space in Russian culture. The members of Pussy Riot themselves describe their performance as a “political gesture.”41 The title of the music video documenting the performance also has a political reference: Punk Prayer – Mother of God, Chase Putin Away! Their decision to perform on the altar in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior was motivated both by the gender restrictions placed upon that space and the alliance between church officials and political leaders. “We needed to sing it not on the street in front of the temple,” writes Pussy Riot, “but at the altar—that is, in a place where women are strictly forbidden (Fig.4).”42 And as for the questionable coalition of church and state they write that “what troubles us is that the very shrine you consider so defiled is so inseparably linked to Putin, who as you say, returned it to the cathedral”43 and elsewhere, “the words we spoke and our entire punk performance aimed to express our disapproval of a specific political event: the patriarch’s support of Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin.”44

In an effort to affect change, to question the imposition and relationships of power within Russian society, Pussy Riot utilized a strategy of spatial transgression as a means to reveal and expose. By “getting-into-place,” a place that was off limits, they utilized a method of “music as performance” to create a transgression that critiqued the nature of exclusion in that space.

Fig.4 Pussy Riot performing in front of the altar at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, 2012. Image courtesy of fact.co.uk/whats-on/pussy-riot-a-punk-prayer. Accessed 11/12/15.

Some of the significant questions that their performance raised included: Why are they excluded from these spaces? Who has prescribed these restraints? What is the purpose of this exclusion? Similar to Mitchell, Pussy Riot’s transgression exposed and subverted the hegemonic forces at work within place, especially those that attempt to gender, politicize, ritualize, sequester, or deify space.

Even though Pussy Riot’s spatial transgression may seem distinct from the other two because of its enactment in actual space, they all share the crucial commonality of calling upon the mobility and spatiality of music to produce a political act. The musicality of the transgressions created an active criticism that becomes spatial, mobile, visceral, and bodily. Through the experience of the music in these spatial transgressions, the listener is moved—not always physically, but opened to a way of being through a metaphorical, symbolic, or material transportation. Recall the words of Sun Ra cited earlier: “The right note or chord can transport you into space using music and energy flow. And the listeners can travel along with you.”45 Or recall how Mitchell’s album is composed as a travelogue, giving the listener a voyeuristic glimpse into her transgressive wanderlust.

By exploring the performances of these three musicians, I have demonstrated some varying modalities of spatial transgressions in music. My aim has been to show that the politics of mobility and spatiality can be conjured in the production of music to develop transgressive geographies. If music has an intrinsic mobility, and “mobility, and particularly the represented meanings associated with specific practices, is highly political,” as Cresswell suggests, music seems particularly adept to the “stepping over” of boundaries.46 The inherent spatial quality of music and “its capacity to reconfigure space” lends itself to this effort as well, since to resist something may indeed sometimes require what Kenneth Frampton calls a “clearly defined domain” to push against or transgress.47 In the form of sounds of transgressive geographies, these disruptions hold significant potential as a means of insurrection and resistance to dominant cultural power formations.

About The Author

Greg Blair, PhD, Associate Professor of Art

Northern State University, Aberdeen, SD

My research interests lie in post-1960 interdisciplinary art practices, environmental aesthetics, indigenous epistemologies, the agency of place, and philosophies of place. Recent publications/presentations include: “Place-Produced Thought: The Agency of Place and the Co-Production of Knowledge in Heidegger” Delivered at The Sitka Institute: Thinking on the Edge. Organized by the Pacific Association for the Continental Tradition and ”The Way We Get By: Aesthetic Engagement with Place.” Published in The Journal of Art for Life, Vol.6, Issue 1.

- Nikolay Polozov in Pussy Riot!: A Punk Prayer For Freedom by Pussy Riot (The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2012). 77. ↩

- Georgina Born, Music, Sound and Space: Transformations of Public and Private Experience, 2015. ↩

- Owen Chapman, “Sound Moves: Intersections of Popular Music Studies, Mobility Studies and Soundscape Studies,” Journal of Mobile Media 7, no. 1 (2013). Accessed 10/19/16, http://wi.mobilities.ca/sound-moves-intersections-of-popular-music-studies-mobility-studies-and-soundscape-studies/ ↩

- Simon Frith, Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1999). 75. ↩

- Will Straw, “Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Scenes in Popular Music,” Cultural Studies Vol. 5, Iss. 3 (1991). 368. ↩

- Ibid. 369. ↩

- Roy Shuker, Popular Music: The Key Concepts, 2nd ed (London ; New York: Routledge, 2005). 121. ↩

- Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009). 3. ↩

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, (New York: Vintage Books, 1990). 7. ↩

- Birgit Bräuchler and John Postill, eds., Theorising Media and Practice, Anthropology of Media, v. 4 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2010). 7. ↩

- Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (Vintage, 1994). xvii. ↩

- Robert Deuchars, Ronald Fischer, and Ben Thirkell-White, “Creating Lines of Flight and Activating Resistance: Deleuze and Guattari’s War Machine,” accessed February 12, 2016, http://www.philosophyandculture.org/seminar1003deuchars.html. ↩

- Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays (Stanford University Press, 2009) 24. ↩

- Simon Frith in Questions of Cultural Identity, Stuart Hall and Paul Du Gay, eds. (London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1996). 109. ↩

- Ibid., 111. ↩

- Ibid., 114. ↩

- Jane K. Cowan in “Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Scenes in Popular Music” by Will Straw, Cultural Studies Vol. 5, Iss. 3 (1991). 380. ↩

- Simon Frith in Questions of Cultural Identity, Stuart Hall and Paul Du Gay, eds. (London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1996). 125. ↩

- John F. Szwed, Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, 1st Da Capo Press ed (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998). 29-30. ↩

- Ibid. 172. ↩

- Tim Cresswell, In Place/out of Place: Geography, Ideology, and Transgression (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996). 176. ↩

- Szwed, Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, 175. ↩

- Ibid. 172. ↩

- Ibid. 312-313. ↩

- Ibid. 325-26. ↩

- Idris Ackamoor in Sun Ra Changed My Life: 13 Artists Reflect on the Legacy and Influence of Sun Ra, accessed 10/20/16, http://thevinylfactory.com/vinyl-factory-releases/sun-ra-changed-my-life-13-artists-reflect-on-the-legacy-and-influence-of-sun-ra/ ↩

- John Rockwell, “Joni Mitchell Recaptures Her Gift,” New York Times, December 12, 1976. ↩

- Jessica Hopper, “Joni Mitchell The Studio Albums 1968-1979,” Pitchfork Media, November 9, 2012, accessed 11/10/15, http://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/17269-the-studio-albums-1968-1979/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, America (London ; New York: Verso, 2010). 88. ↩

- Ariel Swartley, “Hejira – Joni Mitchell,” Rolling Stone, February 10, 1977. ↩

- Michael Walzer, Interpretation and Social Criticism, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1993). 60. ↩

- Jessica Hopper, “Joni Mitchell The Studio Albums 1968-1979,” Pitchfork Media, November 9, 2012, accessed November 10, 2015, http://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/17269-the-studio-albums-1968-1979/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ariel Swartley, “Hejira – Joni Mitchell,” Rolling Stone, February 10, 1977. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Michel Foucault, Intellectuals and power: A conversation between Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze, accessed 11/10/15, http://libcom.org/library/intellectuals-power-a-conversation-between-michel-foucault-and-gilles-deleuze ↩

- For Mitchell’s interpretation of the story of Adam and Eve, and how it has been used as tool of repression, see Mitchell in Joni Mitchell: in her own words : conversations with Malka Marom, Joni Mitchell and Malka Marom, (Toronto: ECW Press, 2014) 192-193. ↩

- Ariel Swartley, “Hejira – Joni Mitchell,” Rolling Stone, February 10, 1977. ↩

- Pussy Riot, Pussy Riot!: A Punk Prayer For Freedom (The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2012). 39. ↩

- Ibid. 15. ↩

- Ibid. 15. ↩

- Ibid. 26. ↩

- Ibid. 42. ↩

- John F. Szwed, Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, 1st Da Capo Press ed (New York: Da Capo Press, 1998). 175. ↩

- Tim Cresswell, “Towards a Politics of Mobility,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (2010) 21. ↩

- Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Hal Foster, Ed., (New York: New Press, 2002). 25. ↩