For Ronald Hitzler

“The current official guidebook of the city, endorsed by city mayor Eberhard Diepgen, is divided into two parts: The Past and The Future. The present is conspicuously omitted. It is as if the only permitted celebration of the present is the Love Parade, whose participants stray distractedly from the painful debates about the past and the future and simply hang out at the contested sites from the Brandenburg Gate to the Victory Column, treated by Berliners as benign invaders from outer space.”

Svetlana Boym

I. History, Updated and Rewound.

Finally, the history of the Love Parade in Berlin is at an end. What was for a number of years the biggest festival of electronic music in Germany, and, indeed, the world, will no longer see the sites of the capital. As early as 2003, the Love Parade appeared to have been banished; yet, after a two-year hiatus and against all expectations, it returned in 2006. Plagued with financial difficulties, it was finally saved by Germany’s biggest fitness chain, McFit — binding the uneasy twin-functionality of techno as the music of transcendent experience and the music of treadmill aerobics: rave freaks and health freaks united. However, the alliance proved uneasy. McFit has established a monopoly over the parade, and the two main stars connected to the parade’s founding and history — Dr. Motte and Westbam — are no longer board members.1

| Video 5: Dr. Motte and Westbam: “Love Parade 2000” |

In 2006 Dr. Motte even gave his parade speech at the Fuck Parade, an underground anti-Love Parade that started in 1996.2 The return to the capital ultimately proved short-lived. The Love Parade has now moved to a new home: the Ruhr Valley.

Yet the parade forges on, and its unlikely comeback is, in fact, not so unlikely. From its inception, the Love Parade has been declared dead every year. The pressure to end the parade has been immense — from public organizations, popular sentiment, and branches of the techno scene. Each year, people voice hopes that the Love Parade will end, so that citizens can be free from the raver-proles — the paradigmatically postmodern rebels without a cause — flouncing through their streets. Unlike traditional annual events, the Love Parade’s future is always in crisis. Nevertheless, the Love Parade has survived for 20 years and is now entering what I would call its fourth historic stage.3

The first stage from 1989 to 1995 consisted of its rapid development out of the Berlin underground. The event occurred annually on a major shopping boulevard, the Kurfürstendamm, in the heart of West Berlin.

| Video 1: Dr. Motte and Westbam: “Sunshine” (1997) All video examples are excerpts unless otherwise noted. |

| This was the first of an annual series of a Love Parade anthem videos. It was produced already after the Love Parade had moved to Die Straße des 17. Juni. However, the vast majority of the footage comes from the Love Parades that took place on the Kurfürstendamm. At the same time, the video established the preferred subjects of the parade in its fully fledged pop stage: girls gone wild, gay boys, Brazilian carnival references, hooligans on lampposts, and dancing masses. Exaggerated stories of nudity and sex acts were often told regarding the Love Parade; but throughout its history, the Love Parade remained a rather conservative display of bodies and fashion. See also the 1995 Love Parade documentary Love is the Message for a subcultural representation of the parade’s early stage. |

Initially, it was known primarily in Berlin, but its fame quickly spread throughout Germany and the world. The history from 1989 to 1992 has been recently recounted in the superb film We Call It Techno!: A Documentary about Germany’s Early Techno Scene and Culture (2008). 1992 proved to be a fateful year for techno, when the first major pop techno hit, U96’s “Das Boot,” stormed the German charts while Germany’s major popular media, including the teen magazine BRAVO, began reporting extensively on the Love Parade and the techno scene. These reports included a surprisingly well-informed dictionary entry, describing a tour of Berlin’s original “club mile.” (Click to view magazine images) The second stage lasted from 1996 to 2000, solidifying the parade’s reputation as an international phenomenon. 1996 can be described as the second fateful year of pop techno, when the Love Parade made the move to Die Straße des 17. Juni to forever stamp the impression of techno on Germany’s national symbol, the Brandenburg Gate.4 In this same period, the first Berlin “club mile”on Leipzigerstraße and Friedrichstraße dissolved with the closing of the Bunker and E-Werk clubs. The Love Parade replaced the club mile in this district and from then on played its crucial role as an event right on the former border of East and West Berlin. These years saw the parade’s size grow to its highest attendance at approximately 1.5 million in 1999.

| Video 2: Dr. Motte: “Live at Love Parade 1999” |

| The acid techno mix by Dr. Motte here squarely falls with the style his usual DJ sets; however, they contrast starkly with the pop Love Parade anthems he produced with Westbam — targeted for a larger audience and tourists. The DJ track selection remains strikingly retro-underground and was probably a surprise for many of the visitors not connected to the techno scene. |

A map of Germany, with the Ruhr Valley highlighted in red and Berlin in yellow.

During its third stage from 2001 to 2006, the Love Parade changed rapidly. In that year it lost its legal status as a political demonstration, which exasperated the economic challenges of staging the parade. This status had guaranteed that the city of Berlin pay for the security and the cleanup of the enormous waste left by the attendants.

| Figure 1: A map of Germany, with the Ruhr Valley highlighted in red and Berlin in yellow. |

Without this status, the Love Parade had to finance these matters itself. Furthermore, it saw a decline in attendance and captured less of the media spotlight in Germany. The Love Parade came to be seen as merely another example in the phenomenon of the techno parade.5 These challenges ultimately resulted in the canceling of the Love Parade in 2004 and 2005. But at the same time, partnerships began with other cities around the world — since 2001, Love Parades have occurred in Cape Town, Vienna, Santiago de Chile, Mexico City, San Francisco, and most successfully, Tel Aviv (see Video 3). The fourth stage, still in development, began approximately in late 2006 with the takeover by McFit and the parade’s subsequent move away from Berlin (see Video 4). The official plan of the McFit organization is for the Love Parade to be held in the following cities of the Ruhr Valley: Essen (2007), Dortmund (2008), Bochum (2009), Duisburg (2010), and Gelsenkirchen (2011).6 This multiyear plan has ensured that the Love Parade’s identity will be further distanced from Berlin.

| Video 3: The Love Committee: “Access Peace” (2002) |

| This 2002 anthem video shows images from various Love Parades around the world, demonstrating the parade organization’s new attempts to represent the Love Parade as an international movement. Berlin was to be represented as the birth city and host of the most important event, but the parade was no longer to be associated only with Berlin. |

| Video 4: The Love Committee: “Love is Everywhere (New Location)” (2007, Ministry of Sound, Germany) |

| This 2007 anthem video has a compilation of images from all three stages of the Berlin Love Parade, as well as images of international parades where “love is everywhere.” However, the new geographic “location” of the parade in the Ruhr Valley is clearly represented in the anthem lyrics and the motto of 2007. An advertisement from McFit plays at the end: “The Love Parade is brought to you by McFit: Simply look good.” |

However, the Love Parade’s 17-year-long history with the city of Berlin has clearly left a mark in Germany and Europe. Images from the second stage in particular dominate popular memory both in Germany and worldwide. It was during this time that the Love Parade became a place of pilgrimage, not only for ravers, but for people from all branches of society, urged on by the historically self-reflective demand: “you need to experience it at least once.” In that time of its greatest extravagance, it morphed into a combination of techno party and pop celebration. The enormity of this party, so soon after German reunification, provoked a wide and intense range of reactions.

With these conflicts in mind, I want to revisit the Love Parade’s relationship to Berlin as a city with a specific political-cultural history. In the first section, I examine debates about the Love Parade as a particular form of techno-rave gathering, and further set the specific challenges that the urban geography and history of Berlin posed for the parade in its second historical stage. These conflicts will be set in the context of the Berlin techno scene(s) and their own quarrels regarding the parade. In the second section, I concretize issues of geographic place and space, visual representation, and mass concerts through visual-sonic examples from the film be.Angeled (2001), the only film drama to centrally address the Love Parade, and a collection of Berlin techno tracks that represent the city in conflicting ways. My conclusion traces the developments of Berlin techno in the post-Love Parade era.

In dealing with the relation of techno music and Berlin, Adam Krims’ theorizations of the post-Fordist city, tourism, cultural industries, and the musical representation of cities in Music and Urban Geography form much of the theoretical backdrop for my project. My study will theorize and explain how post-unification Berlin has provided a special set of constructions of the “urban ethos.” Krims writes,

It is the scope of that range of urban representations and their possible modalities, in any given time span, that I call the urban ethos. The urban ethos is thus not a particular representation but rather a distribution of possibilities, always having discernible limits as well as common practices. It is not a picture of how life is in any particular city. Instead, it distills publicly disseminated notion of how cities are generally, even though it may be disproportionately shaped by the fate of certain particular cities, especially New York City and Los Angeles. (Krims, 7)

In this article, I hope to draw out the tension in Krims’ statement between the notion of urban life in general and the particularity of city histories and structures. First, I want to consider Berlin’s recent and arguably exceptional history as a divided city; second, I want to keep in mind the more general history of rebuilding bombed-out cities that has formed a central narrative thread in the German postwar urban ethos; this points to urban understandings that can differ from the primarily Anglophone histories that Krims examines. In this broader theoretical context, the history of Berlin and the Love Parade is a history that sets many of the late-modern tensions regarding the social place of electronic dance music (EDM) and urban life in relief, touching on questions of agency, rebellion, authenticity, and the future of the counterculture. Krims’ call for musicologists to engage with urban geography and vice versa falls on sympathetic ears; for if there is any European capital that, throughout the twentieth century, has seen popular music and urban representation so closely intertwined, then it is Berlin — from cabaret, to punk, to techno, and beyond.7

II. Party Architecture

The move of the Love Parade in 1996 represented a fundamental change, indeed a crisis, in techno’s social position. Since the parade had begun in the fortuitous year 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall, it had already symbolically marked the techno scene’s association with a reunited Germany. In the early 1990s, the ferment of change in Berlin created a complicated picture of Berlin techno. A mix of organizations, venues, labels, and EDM styles has ensured a constantly evolving, often contradictory, picture of techno.8 Indeed, to speak of a single techno scene is simplistic, especially for a city like Berlin.9

To try to grasp the stratification of the scene, I would like to point to four historically important wings of Berlin EDM. While I don’t want to hide the fact that this is a kind of shorthand, it nevertheless provides a more complex picture than simply referring to “Berlin techno.” The division of these four scenes reflects interesting organizational and cultural trends of Berlin city districts. It also makes clear that the historical change in Berlin EDM is closely intertwined with the transformation of the urban landscape of East Berlin — above all, the transformation of Mitte, Prenzlauer Berg, and Friedrichshain:10

i. The pop techno scene (Charlottenburg: location of labels Low Spirit and Vandit): This scene centers around Berlin’s two most famous EDM stars: Westbam and Paul van Dyk, and their respective labels Low Spirit and Vandit. They remain associated with megaraves and the pop cultural call for “the raving society.” The organization and economy of the Love Parade was closely connected to this scene. Its main journalistic organ, the Berlin fanzine Frontpage (itself located in neighboring Schöneberg), was key to the rise of pop techno.

ii. The techno-house scene (Kreuzberg: location of Tresor, SO-36, Hardwax, Spacehall and Groove magazine): This scene originally developed around the UFO club, and then the Tresor and E-Werk clubs. It has provided a relatively stable club culture over time, relying upon the long-established countercultural tradition of Kreuzberg. This scene later crystallized around the Tresor label and club, with other important labels such as Kanzleramt in the vicinity.

Figure 4: Covers of compilation albums from the Tresor record label

iii. The minimal-electro scene (Prenzlauer Berg/Spandauer Vorstadt: location of BPitch Control, m_nus, International DJ Gigolos, and De:Bug magazine): This scene can be closely related to the transformation of the district of Prenzlauer Berg from its rapid reconstruction in the 1990s to settled yuppie life of the 2000s. This scene has become the most prominent “Sound of Berlin” since the 2000s. With the decline of the “pop techno” scene in Berlin, minimal/electro has arguably taken over a number of its elements.

iv. The hardcore scene (Friedrichshain: location of Ad Noiseam, Praxis, and RAW-Temple): This scene consists primarily of more dissonant and noise-oriented EDM genres, deriving inspiration partly from industrial and hardcore punk. Examples include breakcore, gabber, and drum & bass. Wolle XDP, Alec Empire and the band Atari Teenage Riot, Christoph Fringeli, and Current Value are examples of some DJs/producers associated with this scene. Leftist, squatter, and anarchist scenes are also associated with Friedrichshain. The hardcore scene’s general history begins with the Tekknozid Raves and the Bunker club in the early nineties. Currently, its most well known gathering is the Fuck Parade, founded in 1996 as an oppositional parade following the Love Parade’s move to the Brandenburg Gate and to protest the closing of the Bunker club.

These categorizations reflect only partially, however, real geographic differences in scene structures; the various scenes tend rather to utilize the symbolic value of these districts. Occasionally, these differences can result in political-economic and/or aesthetic-cultural conflicts, but there remains an impressive amount of exchange. For example, at Berlin’s most famous club currently, Berghain, one can find techno, electro-minimal, and breakcore parties all taking place within a single week. These various scenes thus congregate at the current club mile stretching the borders between Prenzlauberg, Kreuzberg, and Friedrichshain. What is striking in this new structure is the relative absence of the pop techno scene; the history and fortunes of pop techno in Berlin were indeed closely connected to the rise and fall of the Love Parade.

However, back in 1996, the geographic move of the Love Parade represented the culmination of the goals of pop techno protagonists to transform techno from subculture to pop industry. The move of the Love Parade to Berlin Mitte, as a capital city with significant flows of tourists, meant a move to a primarily tourist and governmental district. As noted, this move occurred at the same time as the disintegration of the old club mile on account of Berlin’s inevitable transformation as the new German capital. This development created a flurry of heated debates as to what the parade signified with respect to rave culture.11

The notion of raves has a complicated history. A rave, as the term is popularly used, simply means any event consisting primarily of EDM. However, this broad definition can be counterbalanced by a definition that considers not just music, but the party’s social structure.12 In its strictest (and idealistic) definition, the term represents a heterotopia with multiple components, continuing principles that were pioneered by mobile discotheques, Afro-Caribbean ‘sound systems,’ the free festival movements, and Hippie groups such as the New Age Travellers.13 One group that was legendary for its strivings toward and battles over these ideals was the Spiral Tribe in England.14 In Berlin, this movement was associated with the hardcore scene with its Tekknozid raves and the Bunker club. Accordingly, the claim to a party’s status as a “rave” can be challenged if it ignores any of these components. A list of ideal conditions based on subcultural ideology can be formulated as follows:

(1) Musical: The party consists of EDM, played by DJs who ideally do not require payment and do not perform on a raised stage above the partiers. Equality between performers and partiers is maintained.

(2) Geographic: A new location is found, never before imagined as a place to hold parties. This represents the reclamation and reimagination of a space neglected, made banal, or declared legally off-limits.

(3) Economic: The party is free and organized on a volunteer basis. No corporate advertising is involved. In the spirit of equality, musicians do not play for profit.

(4) Political: Proselytizing based on certain platforms is not allowed. The political component is expressed through music, dancing, art, and progressive social interaction, not banners and speeches. Nevertheless, commitment to certain principles, especially non-violent and anti-establishment attitudes, is assumed; there are usually expectations that members show evidence of subcultural capital.15

(5) Legal: The party is illegal, which results in a number of economic-political benefits. Freedom is understood in a number of forms. Taxes are not paid to the state; anyone of any age is welcome and does not need to fear being searched. Participants are free to use drugs without the fear of arrest, though they must be responsible for their actions. These components are closely intertwined, and changes in any of them can radically alter the party architecture. Of course, in the actual history of EDM parties, all sorts of organizational structures have formed that reflect the above ideals to widely varying degrees, and as a result, the term rave can cause confusion.

The question of urban geography is thus intertwined with larger political issues. As stated, raving in its stricter definition traditionally engages in a process of geographic exploration; it takes derelict, illegal, and abandoned spaces and transforms them briefly into party places. These spaces are usually one of two types. First: urban sites such as abandoned warehouses — thus, by necessity, indoor parties. This kind of warehouse party emphasizes the postmodern/post-Fordist states of the city. It explores sites of nineteenth- or twentieth-century industrial production, sometimes nostalgically so. Indeed, it could be described as a bizarre form of post-industrial anti-tourism that takes form as a “postmodern game with the ruins of disappearing industry” (Klein, 152). Second: rural sites such as fields and beaches — thus, by necessity, open-air parties. The very designation open-air emphasizes that the dome of the sky is one’s ceiling as opposed to a ramshackle roof, which creates a different relationship to space and acoustics. In these parties, the odd juxtaposition of electronic music’s hypermodern fortissimo amongst nature’s silence allows for an especially pronounced experience of the nature-culture divide.

In both these types, raves attempt to carve out places of resistance outside the sanctioned spaces of musical consumption: clubs, bars, and concerts. Though as Adam Krims has shown, the distinction of space and place has become ever more tenuous in post-Fordist society (see Krims, 27–60). Furthermore, these traditional sites were also integral to the development of EDM, making their own claims to underground authenticity. In relation to both indoor and open-air practices, urban geography was crucial to the Love Parade’s success and uniqueness as an event. It was the first major event to consider seriously the parade as a possible social form of EDM expression, and the parade form proved particularly effective because it traverses these various party architectures. A parade is in the open air, but it also takes place at the center of an urban space; it thus represents a fusion of warehouse and open-air party on the streets. Nevertheless, the Love Parade only achieved the subcultural ideal to varying degrees. Taking the five components earlier described, the model, as it ultimately transformed in the second stage of the Love Parade, appeared as follows:

(1) Musical: The Love Parade retained EDM as the sole musical genre. A mix of famous and local DJs performed on trucks with designated partiers and professional dancers. However, a central stage raised high above the masses was the special site for the performances of international DJ-stars. Nevertheless, each star only performed for 20 minutes, so a semblance of collectivity was maintained and no single DJ captured the spotlight.

(2) Geographic: Die Straße des 17. Juni, as stated, was the location of the parade. It is the national street of Germany, next to the Reichstag and running up to the Brandenburg Gate.

(3) Economic: The party maintained the democratic ideal of “free entry.” However, attendants had to “pay” for this free entry with a compromise: the presence of corporate advertising and other forms of promotion. The parade was a cash cow for products and marketing of all kinds. The size of the party required an organization of paid employees, the Love Parade Berlin Gmbh, with close relations to the firms Planetcom and Low Spirit Recordings. The official board members of the Love Parade Gmbh included during its second stage Matthias Roenigh (Dr. Motte), William Rötger (father of Maximilian Lenz [Westbam] and Fabian Lenz [DJ Dick]), Klaus Jürgen Jahnkuhn, Sandra Mollzahn, and Dr. Andreas Steuermann.16 The parade provided economic benefits for Berlin business, tourism, and the club scene.

(4) Political: The event remained free from proselytizing. To meet the requirements of a demonstration, Dr. Motte held a short, annual speech mostly consisting of platitudes regarding the parade’s mission. However, interviews and statements made by public figures resulted in a flood of media discourse that accompanied the event throughout the year.

(5) Legal: Police presence was necessary, though partiers were free to enter parade grounds without being searched. The parade held the legal designation of a demonstration for “peace, unity and understanding.”

The Love Parade thus approached the ideal conditions of a rave to varying degrees, and the parade as a social form presented specific challenges. As an event held in the daylight at the center of a metropolis, the partying masses provided a visual and media spectacle that meant music often took back seat or was completely ignored. (Click to view Bravo magzine coverage of the 2000 Love parade)

Above all, the move of the Love Parade to the location in front of the Brandenburg Gate placed it on a piece of geography that is perhaps the most highly contested in all of Germany. The specific urban geography of Berlin provided the occasion for the particular clashes regarding music, space, and place. Constructed between 1788 and 1791 as a symbol of Prussian state power (officially it was a symbol of peace, but its olive branch was exchanged for the Iron Cross in 1814), the gate was later used extensively for military parades during both the Second and Third Reichs. The breadth of Die Straße des 17. Juni was developed during the Third Reich for even grander military parades and as a central street of the so-called East-West-Axis (part of Hitler’s plans for the new metropolis of Germania). Its current name, “The Street of the 17th June,” is a product of the Cold War, named by the FRG in honor of the East German uprisings that took place and were brutally crushed on that day in 1953. The street was renamed just five days after the uprising, and this day became a national holiday. Entitled the Day of German Unity, it was celebrated annually from 1953 until 1990. After the Second World War, the gate became a symbol of Berlin’s, and indeed all of Europe’s, division between East and West, the result of the Berlin Wall running directly in front of the gate. When the wall was finally torn down in 1989, the Brandenburg Gate’s role as a central symbol of the Cold War was solidified.

Accordingly, when the Love Parade moved to this location in 1996, it immediately had to confront a landmark with a volatile history. On one hand, the Cold War caused the Brandenburg Gate to be morphed into a contested site of a divided city, divided Germany, divided Europe, and divided world — registering on numerous levels of the local, the national, the continental (pan-European), and the global. The Love Parade’s organization exploited this history to allow it to be associated alternatively with all of these levels. However, the decision to make Berlin the capital of reunified Germany quickly made the conservative history of the site as a national symbol prominent again. While the official messages from the Love Parade continued to emphasize internationalism, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) attempted to exploit the parade to try to gain support of the youth,17 and the parade’s size and success also inevitably became a symbol of Germany’s new stature. The free movement of young ravers through the Brandenburg Gate inevitably resulted in the parade becoming a pop symbol of German national unity.

Indeed, with the move to the Brandenburg Gate, the Love Parade moved on to the radar screen of the state. This public display meant that the Love Parade had arguably changed from a rave to a Volksfest — from heterotopia to pop mob. It represented an anomaly of massive proportions compared to the other Berlin techno events occurring through the year. Yet the music remained the same as was heard at standard raves and clubs. Indeed, the degree to which the parade maintained its subcultural capital is surprising, since even with its enormous size, neither commercial dance-acts, like Scooter or Blümchen, nor groups from other genres such as rock or hip hop were ever to be found. Therefore, the common criticism that in its second stage “the Love Parade is no longer techno” is based more on arguments from the standpoint of politics and subcultural ideology than from sound musical observation. A more apt musical critique would argue that the parade became too narrow in its focus: the parade embraced techno, house, and trance almost exclusively, to the detriment of other EDM genres. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the DJs performing at the parade remained those who were integral to the club and rave circuit; producers and DJs from not only pop techno, but also techno/house, minimal/electro, and even wings of the hardcore scene were present.

Critique of the size of the Love Parade remained intense, however, and it focused especially on two issues: (1) the commercialization and reactionary elements developing around techno’s lack of social commitment, and (2) the environmental damage incurred by the Tiergarten from the trampling of the vegetation and the corrosion from the enormous quantities of urine. To the first question, a range of apologies were offered. For example, as to whether techno wishes to take over and fuse with pop culture, Westbam answered with an emphatic yes: “Because for us the beginnings in the underground were also always an eruption into a revolutionized popular culture… the restructuring of the entertainment industry in the sense of the raving society belongs to the important tasks of the coming years” (116–117).18 He asks further, “Which revolution wants to stay on the reservation?”, and at one point he cites Kraftwerk’s ideal of elektronische Volksmusik, reflected in their lyric, “Music non-stop. TechnoPop.”19 Such writings are typical of the pop techno faction.

Techno as a social phenomenon indeed expanded with a relentless drive, while remaining unclear as to what the goal of this “raving society” might be. Its chosen subcultural enemy in the 1990s was often rock music (disparaged as guitar or acoustic music), a kind of rekindling of the disco/rock debate of the seventies and eighties. A major reason that techno attacked rock (vaguely linked with punk, metal, and grunge) was due to rock’s turn from the dance floor to the mosh pit. Rock seemed to counter the crippling boredom of everyday life with equally crippling violence and depression. In 1999, many techno fans saw the ultimate proof of the triumph over rock. That year, the Love Parade drew an extraordinary 1.5 million people and went off peacefully, while Woodstock ’99 drew a mere 220,000 people and was beset with rioting, looting, sexual assault, and violence.

Simon Reynolds provides a further possible answer to this conflict in his chapter “Living the Dream” from Generation Ecstasy. He recounts the transformation of London’s football hooligans through rave culture and ecstasy: “The heartless hoolie turned loved-up nutter was proof that Ecstasy really was a wonder drug, an agent of a spiritual and social revolution” (46). Techno offered a rough opposition between two camps: violence, beer, and football versus love, ecstasy, and dance. For Reynolds, raving represents the revolt of a subculture against forms of entertainment that it sees as destructive. The coding of the first activities as masculine and prosaic and the second as gay/feminine and poetic even resulted in the designation of techno as “straight disco music.”20

Transferring Reynolds’ theory from England to Germany, it can be applied to a number of aspects of German techno culture: (1) The transformation of East Germany, a practice closely linked to Berlin with its conflicted praise for East Berlin ravers and disparaging stereotypes regarding provincial “Brandenburg proles” associated with the Love Parade;21 (2) The revolt against the boredom of German utilitarian life and, similar to England, the popular love of beer and football; (3) Perhaps most profoundly, the resistance to Germany’s distinguished tradition of hetero-masculine, dead-serious politics. Regarding this third aspect, the Love Parade’s message, aside from the platitudes for peace, justice, and non-violence for non-violence’s sake, was anti-message- and anti-utility-oriented. The founder of the Love Parade, Dr. Motte, explains his original ideas from 1989 thus: “We’ll make a demonstration. We’ll use no banners, no words, no rally cries, but music.”22 The dream of an event beyond language aimed for all-encompassing acceptance; the only speech was Dr. Motte short talk to fulfill the state’s requirement that traditional, verbal discourse constitute a political demonstration. His ideal of having absolutely no words or rally cries was thus not possible on three grounds: first, it was not legally possible as a registered demonstration; second, advertisements were financially necessary; and third, the claim to anti-discourse requires traditional discourse to utter the claim in the first place.

Irony was Dr. Motte’s main weapon against these compromises. He continues, “And then I reasoned, for that we’ll need a motto.”23 Dr. Motte’s first choice of motto was, I would argue, the most interesting and indicative motto, embodying the political irony with which the parade began: Friede, Freude, Eierkuchen [Peace, Joy, Pancakes] — in a sense, a rally cry against the notion of a rally cry. Unfortunately, many later mottos became boring Anglophone platitudes of self-praise and advertisement, such as “We are One Family” and “One World, One Loveparade”; however, such political irony continued through much of the parade’s history. Specifically, this original motto reflected the ironic clash of Love with the traditional military and political notions of Parade, a tactic obviously borrowed from pride parades. The clash was further reflected in the music video to the first European-wide dance single to invoke the Love Parade: Da Hool’s “Meet Her at the Love Parade.”

| Video 6: Da Hool: “Meet Her at the Love Parade: 1997” |

| Da Hool is a project name of DJ Hooligan, a name appropriate to the Eurotrash styles in this video, epitomized with the fierce leopard outfit of one of the raver chicks and the obsession with sunglasses. |

A temporal clash between partytime and history, the dancers maintain pop ironic distance before the various classic sites of the city; atop the love-trucks that move freely through the reunited city, the various dancers perform camp freakouts. The camera absorbs their attention and acts as narcissistic mirror; the dancers demonstrate that they couldn’t care less about their surroundings. To put it mildly, the poses and countenances of the dancers among these monuments do not conform to the expected, proper composure of a citizen before such structures — and the dancers know it.

The Love Parade’s legal situation was equally as ironic as its politics — registered as a political demonstration, and yet apolitical in terms of its refusal to take up a specific platform or issue. For critics of the Love Parade from the hardcore and techno-house scenes, the parade’s betrayal rested in this relationship to geography and the state. The ideal conditions with respect to these issues were famously articulated in Hakim Bey’s anarchist writings with the notion of the Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ). As Bey argues, “The TAZ is like an uprising which does not engage directly with the State, a guerilla operation which liberates an area (of land, of time, of imagination) and then dissolves itself to re-form elsewhere/elsewhen, before the State can crush it” (101). This notion was important to many in the anarchist faction of the techno-house and hardcore scenes. It was crucial that raves stage illegal events, remain constantly on the move, and not seek out the spotlight of the official media. The Love Parade, however, had become an official demonstration.

According to democratic theory, a demonstration is an oppositional gathering like an uprising. But unlike an uprising, it is an oppositional gathering within the law. For the Love Parade’s finances, remaining within the law became crucial. As stated earlier, it meant that the state would pay for the security and cleanup. The Love Parade is thus distinct from both commercial raves and clubs, which are legal but entirely the financial responsibility of the promoters, and illegal raves, which fulfill Bey’s notion of an uprising more closely. The parade became another case of an organization exploiting a loophole in the law, an event bordering precariously between legal-illegal, public funding, and commercial profit; the responses to this situation included both positive and negative valences. Achim Szepanski, manager of the Frankfurt label Force Inc., termed the social formation of German techno and the Love Parade as the free-time-prison, “Freizeitknast” (Reynolds, 388). Such stances reflected the theoretical formulations of a long tradition of European critical thought, especially Theodor W. Adorno’s and Max Horkheimer’s theory of the culture industry. Rainald Goetz, the central literary figure of the German pop techno scene, dismissed such charges with scorn. Against the screams from the pulpits of “critique,” which he likens to the pulpits of “faith,” he simply grants their wish, according to him, “to sink in the swamp of marginality. Have fun, down there in the trash” (Goetz, Celebration 221).24 On the other hand, Goetz’s way of affirming the vulgar democracy of the parade is not exactly full of praise: “The unhappy creatures, all the tired and worried, the lethargic masses, the disconsolate, the broken, the idiotic who can also tag along, like every fucking person who wants to, to that single beat” (Celebration 223).25 Goetz invites the masses to join in, but he has nothing to say about where they come from and where they go afterwards. This bizarre form of praise reflects at the same time “progressive” Berlin’s prejudicial and often classist distain for the “Brandenburg proles” to be found at the parade.

An affirmative, if more subtly ambivalent, perspective on the parade comes from one of Berlin’s major DJanes, Ellen Allien. She says the following:

A sign that the Love Parade is not dead: as I myself stood there at the Siegessäule, and played some kind of super prole-track, or a commercial-track, in other words, a type of music that I don’t necessarily like, but in that moment it worked so well. There was a break dah-de-dah dah-de-dah and all the hands went up, and all the people simply felt the same thing at that moment. I just found that totally awesome. Then I understood techno again.26

These moments, while easily critiqued, are not so easy to negate experientially, as Ellen Allien admits with reserved astonishment. She describes a kind of musical politics over which she has little control, a tense space between subculture and mass movement carved out in the Love Parade — as she later states, “It’s not so easy to move masses.”27 Indeed, a single individual deejaying for over a million people in one location certainly represents one of the most extraordinary events of amplified sound in modern times. Yet the experiences of the DJs who played at the Siegessäule, as well as the audience, have seldom been described, artistically represented, or even taken seriously. It is to these experiences as represented in film and video that I now turn, to concretize the Love Parade and the encounter with Berlin.

III. Representing Berlin: Masses, Repetition, and Time-lapse Clubbing

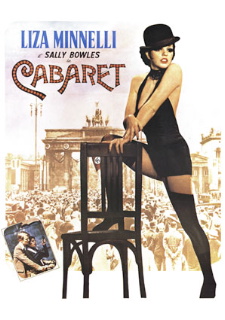

EDM has played a decisive role in constructing post-reunification Berlin’s urban ethos. The urban ethos of EDM as a lure to Berlin, especially in its representations through the Love Parade, reflects many elements of the “abstract city of fantasy” (Krims, 18) that Adam Krims examines in the tradition of pop disco. In its hedonistic, camp, and queer representations, EDM has appropriated themes from one of the most prominent historical cities of fantasy: “Weimar-era Berlin,” supported by a selective memory of freedom and glamour as depicted in films like Cabaret (1968). This urban ethos has become especially important for German musical practice because of the problematic associations that celebratory representations of nature and rural life have with Blut und Boden and romantic associations tainted by Nazi ideology. Though every bit a modern movement, Nazism is often not associated with city life in cultural memory as much as it is with German romanticism and nature. The city offers the potential of

overcoming this past precisely because many old German downtowns were destroyed and new downtowns were constructed in their place. This postwar history differs strongly from the Anglophone cities of Krims’ focus. The potential for constructing a modern urban ethos in Berlin has been particularly strong, as its close association with the Weimar period proves; though as we have already seen, the Prussian, Weimar, Third Reich, and Cold War periods remain in constant tension as Berlin’s most influential historical palimpsests.

How Berlin is represented in EDM takes on various forms both synchronically and diachronically. In this section, I will first explore a number of tracks with either titles or lyrics that invoke Berlin, before proceeding to the film be.Angeled, a filmic representation of Berlin techno. Earlier we observed the relation to Berlin that a pop-techno track like “Meet Her at the Love Parade” offers; its melodic hook promises trashy fun and partytime in the city. This pop anthem inspired many of the Love Parade anthems and videos that followed.

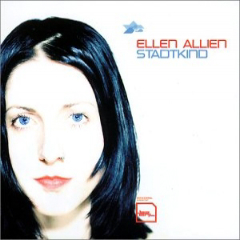

However, tracks from other Berlin subscenes offer different possibilities. For example, the urban ethos of a track like Ellen Allien’s “Stadtkind” (City Child) evokes different associations.

Example 1: Ellen Allien, “Stadtkind” (City Child)

The slick electro track with Allien’s distorted vocals and melancholic tune represents a woman free to move in Berlin, but one who is self-reflective, calm and independent in ways different from the girls gone wild referenced in “Meet Her at the Love Parade.” The track can further be placed in a long line of female musicians and performers who have represented the urban ethos of Berlin as a progressive, feminized space, opposed to the “Fatherland.” Berlin EDM DJanes have been particularly successful in continuing this tradition — from the stardom of the “Rave Queen” Marusha, to label owners like Monika Kruse, Anja Schneider, Gudrun Gut, and Ellen Allien herself. Allien’s lyrics are reserved

and spare, borrowing on the vocal tradition of Kraftwerk, while the track remains an example of Allien’s trademark crossover between Berlin identity, techno, and tourism. It also looks forward to the more refined digital sound productions for a “design-intensive city” (see Krims, 127–62) through its slight tints and carefully modified timbres and soundscapes.

| Figure 8: Cover of Ellen Allien’s Stadtkind |

Figure 9: Other female DJs and label owners in Berlin: Marusha, Monika Kruse, Anja Schneider, and Gudrun Gut

A further representation of Berlin is offered in Alec Empire’s 1994 track “Blutrote Nacht über Berlin” (“Blood-red Night above Berlin”).

Example 2: Alec Empire, “Blutrote Nacht über Berlin” (“Blood-red Night above Berlin”)

| Figure 10:Einstürzende Neubauten’s album Palast der Republik |

Here the uses of the distorted 909 bass and chromatic theme indicate histories of war and alienation. However, it is important to note that such a track is not necessarily an anti-Berlin track. It has the potential to provoke a paradoxical form of “anti-touristic tourism” similar to post-industrial industrial tourism. Not an abstract city of fantasy of the pop disco kind, it offers an industrial city of fantasy that is coded masculine, attractive to punks and other counter cultural elements who yearn for the

Figure 11: The Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche

aesthetics of trash, ruins, and industry to accompany the politics of urban warfare, resistance, and Leftist protest. Such an industrial city of fantasy, or a destructive city of fantasy, is offered in the video of Atari Teenage Riot’s “Destroy 2000 Years of Culture,” (Video 7) which can be read against Krims’ discussion of the city in Kylie Minogue’s video “Can’t Get You Out of My Head” (15–19).

| Video 7: Atari Teenage Riot: “Destroy 2000 Years of Culture” |

Alec Empire, Atari Teenage Riot, and indeed much of the hardcore and techno/house scenes, work here within a tradition of Berlin city representation that was pioneered by the industrial band Einstürzende Neubauten. In the very title of the band (meaning roughly “Collapsing New Buildings”), the relationship of architecture and music are made apparent; the tracks “Kollaps” and “Steh Auf Berlin” from their 1981 album Kollaps remain key examples of architecture and music crossover.

Example 3: Einstürzende Neubauten, “Kollaps” (“Collapse”)

Example 4: Einstürzende Neubauten, “Steh auf Berlin” (“Rise up, Berlin /I Like Berlin”)

Regarding subcultural associations, the very notion of underground is a geographic one. Associations with abandoned buildings and bunkers recall the Second World War, thus distancing the musical city from its preferred historical associations with Weimar freedom and decadence. The reference to urban warfare and destruction similarly reference the mass bombings of German cities in World War II. The specific history of East Berlin, which left many facades unrenovated and bombed ruins exposed for decades, reminded one of a history that was directly preserved only in few points in West Berlin, such as the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche.F

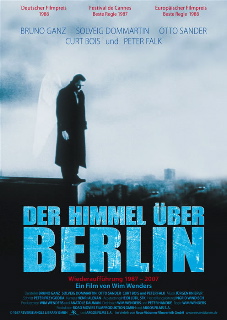

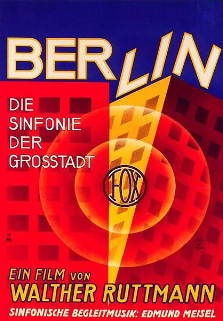

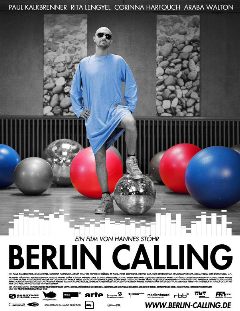

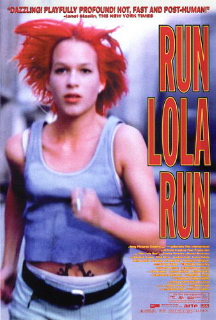

We saw how such conflicted representations of Berlin’s urban history played out in the Love Parade’s ironic practices discussed earlier, and this also finds echoes in the film drama be.Angeled (2001). I find exploring the Love Parade and Berlin in the medium of film to be especially important because of Berlin’s rich history of intermedial representation through music and film — from Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) to Der Himmel über Berlin (1987) and Run Lola Run (1998), and most recently in the techno film Berlin Calling (2008).

Figure 12: Cover art from Berlin-themed films

| Figure 12: Cover art from Berlin-themed films |

be.Angeled takes place primarily on one day, July 8, 2000, at the 12th Love Parade. Though not a commercial or artistic success, the film has become a unique document of the Love Parade’s second stage. It is also a significant contribution to the post-Trainspotting (1996) EDM film genre; in particular, be.Angeled is comparable to the films Human Traffic (1999) and Groove (2000). These three films function somewhat like fictional ethnographic studies of EDM scenes in their respective cities, each offering collective narratives of a single party in the time span of 24 hours; however, in many ways these films differ radically.28 Groove recounts an illegal rave through the lens of subcultural ideology, highly affirmative about the San Francisco rave underground. Human Traffic portrays characters committed to the ideology of the Cardiff EDM scene, though they remain far more cynical about their possibilities for agency. They attend a legal club, as opposed to a rave, and their sense of community is expressed more through a support network of friends and lovers than as members of a scene. be.Angeled, on the other hand, offers a disturbing narrative of a mass gathering of proportions unmatched in either Groove or Human Traffic. Especially in comparison withGroove, the film stands as an important example of the radically different place EDM holds in European pop culture; Groove recounts a party of a hundred or so people, whereas be.Angeled featues a party of over one million. Aerial shots and extreme long shots are far more common in be.Angeled, giving a sense of magnitude that is not present in the other two. In short, while the first two films deal with club crowds, this film deals with masses.

be.Angeled, like the other two films, is constructed as a collective narrative; it tells eight stories of love, disaster, and international travel that intersect at the Love Parade. The director, Roman Kuhn, claims the following regarding these narratives: “We wanted to tell stories that could really happen at the Love Parade.”29 This statement is particularly surprising. Given that there have been few incidents of death or violence at the Love Parade, the violence that occurs in the film is staggering. In the eight stories involving roughly fifteen main characters, there is one murder, one suicide, three rapes, and numerous acts of psychological and physical violence, including a scene where one raver pumps a series of industrial staples into the genitals of her ex-boyfriend as revenge for infecting her with AIDS, subsequently committing suicide herself.

The troubling narrative is reflected in the clash between non-diegetic ambient music and diegetic dance music, reinforcing the traditional divisions between a dancing and listening subject. The ambient music repeatedly serves as commentary on the party; it infiltrates the party atmosphere and transforms the diegesis into a space of tragedy. Usually the sonic accompaniment to chillout rooms at raves, it is reconfigured as the music of critique — it encloses the characters as monads, whose interiority radically breaks with the ostensible good vibes of the party community.30 These breaks reflect the volatile narrative threads of the characters, whose various paths jumble and intertwine chaotically. In this sense, be.Angeled further contrasts with Groove and Human Traffic, which ultimately follow teleological paths toward climax and release.31F

I point out these aspects because the film profits from the sensationalized fears of German society that were connected to the Love Parade. Above all, these fears center around two issues: mass gatherings and repetitive music. I would argue that it was primarily the mix of these two aspects that caused the Love Parade to be the locus of such controversy. The Love Parade is certainly not the only mass event or concert to take place in front of the Brandenburg Gate; every year, events ranging from the New Years Day celebration to the Christopher Street Day Parade are found here. However, the fear of mass gatherings in Germany of any kind since the Third Reich and the long established tradition in European thought linking repetitive music to regression and marching meant that the Love Parade was viewed as particularly problematic. The critical writings of figures such as Theodor W. Adorno, Jacques Attali, and Wim Mertens on popular dance music, disco, and minimal music, as well as the popular reception of Freud’s theories of repetition compulsion and the death drive, undergirded fears and critiques of EDM. Attali writes for example, “The popular dance, which has in part become a concert, is a release from violence that has lost its meaning. Carnival without the masks and the channeling of the tragic; in which the music is only a pretext for the noncommunication, the solitude, and the silence imposed by the sound volume and the dancing” (118). The Love Parade and German EDM were caught here in the clash between a queer politics of jouissance and a Leftist dialectical politics of critique. While the critique of repetition has been an intense and especially Eurocentric phenomenon, recent scholarship has countered such orthodoxy. Though space and time do not allow for an appropriate recounting of the repetition debates, I would like to point to the writings of Mark Butler, Luis-Manuel Garcia, and Robert Fink, all of whom offer key new studies of repetition and, specifically, EDM. Butler focuses on listening pleasures of metrical dissonance, process patterns, and loops; Garcia counteracts regressive notions with the notion of “satiation, process, and creation pleasures” (Garcia, 3.4); while Fink employs the notion of “recombinant teleology.”32 All these authors point toward various anti-teleological notions of repetition as singularity, as process, as desiring production, as mathematical sublime, and so forth.

Beyond such sensationalized fears, two aspects are important with respect to the film’s depiction of music and the city: 1. The relationship of tourism and globalization to Berlin represented in travel (by train, car, and U-Bahn) as modern forms of pilgrimage. 2. The homology of monumental architecture and the political relation of the DJ star system to the masses.

Regarding travel, the characters in be.Angeled are constantly in transit: either toward Berlin as tourists, through the parade itself, or through the city. The post-parade travel through the city is a particularly important aspect, which reinforces the association of techno with all of Berlin. EDM is a music designed for massive sound systems; indeed, with the Love Parade and its specially prepared outdoor sound systems, one could not escape the feeling that whenever one was in the general vicinity of the parade, techno had become the virtual sonic architecture of Berlin. So while films and audio recordings can reproduce the styles, settings, and the “music itself,” they cannot reproduce the bodily experiences of being immersed in the masses and the fortississimo music. In this respect, a cherished characteristic of techno sound systems by many clubbers is the extraordinary reverberating effect of the basic 4/4 bass kick — for example, when one is waiting outside or approaching a club with an appropriately loud sound system, the bass has an especially distorted and unique sound that merges with the vibration of the building’s materials, especially its rattling metals. In the case of Berlin during the Love Parade, when one walked the streets, the distant echo of this bass drum could be heard virtually anywhere. The club tours of the characters in be.Angeled represent this to a degree. Such tours were part of the “Love Week” surrounding the actual parade — Berlin was packed with special club nights, concerts, and raves in the days prior to and following the parade. Groups of tourists or locals would establish makeshift DJ booths and sound systems throughout the city — in bars and cafés, on the streets, in the parks, and in their cars — and the U-Bahns and busses had special night routes packed with ravers. Thus, in practically all parts of the city, especially on the day of the parade itself, wherever one traveled, one was liable to hear the distant sound of 4/4 bass drum or see ravers somewhere — giving the feeling that Berlin was indeed a techno city.

Travel is further explored in the film through language. Reflecting the international draw and tourist aspects of the event, the film mixes between the German, English, and French languages, though English plays an especially prominent role as a marker of global pop culture. While this linguistic mix ostensibly critiques nationalism, it is important also to recognize that these languages are the privileged markers of bourgeois globalization and the official languages of the European Union. For example, Turkish and Polish are notably absent from the film. Nevertheless, this linguistic mix reflects a concern of the film: the possibility in a global city of genuine communication (whether through language, music, dancing, or violence) and genuine community (whether between lovers, ravers, friends, family, or foreigners).

These problems of communication are curiously paralleled in the one narrative thread that deals both with the cultural divide between East and West Germany and the music industry: the conflict between the characters Mark Spoon and Lexy, real-life DJs playing “themselves.” Within the film, they play two DJ types: the first, a prole: old, fat, ugly, jaded, but also an experienced member of the first Love Parade generation; and the second, a yuppie: young, slim, sexy, stylish, inexperienced, idealistic — but transitioning rapidly to the jadedness of the former.33 Spoon and Lexy’s conflict is further reflected in their musical choices. Lexy represents the minimal/electro scene, while Spoon represents the pop techno scene, or in Lexy’s terms, “Asi-Scheiss-Trance-Proll-Musik” (roughly translated: “Asshole-shitty-trance-prole-music”). That Lexy comes from Dresden (the former GDR) and Spoon comes from Frankfurt am Main (the former FRG) is significant for the

national narrative of the Love Parade. Lexy is trying to make it as a young Ossie while Spoon is already a well established Wessie— socially and geographically, East and West meet at the parade. While in Berlin, the parade indeed functioned as a symbol of what techno was performing daily in towns and cities throughout Germany: a way for young Germans to negotiate a newly reunited nation and a new Europe.

In their first meeting before DJing, Lexy insults Spoon, saying he is a sellout and has snorted away half his brain with cocaine. Their second meeting is at the DJ stage around the Siegessäule. To explain: the Love Parade schedule, as it developed and solidified in its second historical stage, divides into two halves. The first half, the warm-up, occurs between roughly noon and 6 p.m., in which the individual “love trucks” have separate lineups of DJs, and thus, each truck plays different music. The second half takes place between 6 p.m. and 11 p.m., when night arrives and the lightshow begins. All the trucks become synchronized when the sound system around the Siegessäule starts up. From this point on, all the participants are dancing to the same music, which is spun by star DJs who alternate rapidly with 20-minute-long sets. The ideal of fusion into the party atmosphere is in this way sonically represented by the unification of the various sound systems.

| Video 8: Marusha Live at Love Parade 1998 |

| This performance takes place in the early evening, a few hours before sunset. Marusha was one of the few DJanes who regularly performed at the star DJ booth. |

| Video 9: Sven Väth Live at Love Parade 2000 |

| The lightshow and onset of night gives a strikingly different feel to the Love Parade here versus the daylight performances. Sven Väth’s electro mix points to the rising popularity of this music in Germany and Berlin at this time. |

Lexy’s and Spoon’s second meeting is comprised of two sequences that deal with their DJ performances. Each sequence begins with a low angle shot with symmetrical composition of a staircase leading up to the Siegessäule, worthy of the column’s monumental architecture. The discursive mix of the techno-stars with the Wilhelminian architecture is presented in ways comparable to the “Meet Her At the Love Parade” video. Lexy and then Spoon head up the staircase as monuments themselves: saints entering heaven, oddball politicians acknowledging their followers, or gladiators entering the arena. In the film, nondiegetic ambient music accompanies both Lexy and Spoon as they prepare for their performance. With Lexy, the sounds of a steadily increasing heartbeat mark the approaching terror of having to perform before a million souls for the first time.

| Video 10: be.Angeled (2001): Lexy |

In Mark Spoon’s case, the ambient sounds accompany a veteran from the first generation set in his ways, relishing the power he has over the masses. All we witness is his ironic smirk. Indeed, as Love Parade representative, Spoon is the most interesting character in the film precisely because he never speaks — he symbolizes the parade as the mute icon with the ironic smirk. Yet, as has been shown, this mute smirk was carefully calculated and discursively productive in its own right. What actually speaks is the dialectical clash between monumental architecture and the massive outdoor EDM disco; between Prussian militarism, a divided Germany, and Eurotrash; and between history and partytime — forever marking the Love Parade as one of the most important symbols of fin-de-siècle Berlin.34

| Video 11: be.Angeled (2001): Spoon |

When Spoon heads up, he appears to approach Lexy menacingly; but Spoon makes an offer of reconciliation. He even kisses Lexy on the cheek and celebrates Lexy’s first mix at the Love Parade. The joining of the hands of the Ossie and Wessie DJs as the crowd cheers is indeed a subtle, if tense, celebration of national unification. However, when Spoon takes the decks, a new ambient sound is heard — that of the record slowly speeding up. The crowd is wound up, but Spoon suddenly splits Lexy’s hit-record in two. His trance track “Storm” begins, and the pop party resumes.35 Timelapse photography follows, and the day quickly passes into night. This technique echoes the opening scene of Run Lola Run; however, this form of timelapse photography does not evoke Berlin in the excitement of change but one seemingly bored with its own spectacle after a decade of excitement. Indeed, timelapse photography was an appropriate marker of 1990s Berlin; the trauma of the wall and the unfreedom of travel for nearly 40 years resulted in a decade of images and experiences of movement — running and dancing on the streets. This delight in timelapse photography, the winding up and winding down of record speeds and film speeds, accompanied a city in rapid change — and simultaneously consciously constructing and reflecting on of that change.

The very fact that be.Angeled was produced indicates the historically self-reflective awareness of this event as “making history in the present.” The parade organizers were also self-conscious of this history. be.Angeled was filmed during the last year of the Love Parade’s designation as a legal demonstration; the 2001 video “You Can’t Stop Us” acted as a kind of summary of the Berlin history of the Love Parade as a means of challenging the loss of this designation. Including images from its early days to the present, the video is an anthology of the pop imagery that will always be associated with the Love Parade: go-go dancers, love trucks, Brazilian carnival allusions, Brandenburg proles and ravers on street lights, gay boys, dancing girls gone wild, and various Star-DJs (including some extra clips from be.Angeled). As far as Berlin was concerned though, the video’s claim “You can’t stop us” was not prophetic…

| Video 12: The Love Committee: “You Can’t Stop Us” (2001) |

IV. What remains, or the Comeback

… in fact, only a year after the federal government was fully settled in Berlin and the Reichstag was inaugurated, the Love Parade lost its status as a demonstration. The Love Parade remains a pop icon of the Berliner Republik’s beginnings; but by the time the capital completed its move from Bonn to Berlin, the major part of the Love Parade’s history with the city had run its course. Its place in the now fully established Berliner Republik is, at least for now, elsewhere than Berlin.

In the post-Love Parade era, Berlin retains EDM as a major attraction and remains in many respects a key city for techno culture. Tobias Rapp’s recent book, Lost and Sound: Berlin, Techno, und der Easyjetset (2009) explores the new club mile that has arisen since 2004 and the new economy of youth hostels and cheap airline club tourists, or “Easyjet-ravers,” in Berlin. Rapp writes, “The Easyjet-raver is the decisive subject of European nightlife of the zero years. He quietly arrived on the scene but has developed into the most important subcultural figure of the present” (78–9). The continued importance of Berlin as a city of techno-tourism was underscored in 2009 with the crowning of the Berlin club Berghain as “Best Club in the World” by the British journal DJ Mag. DJ Mag captures Berlin’s typical promise of unbridled (or bridled, depending on your preference) hedonism through its writings on Berghain: “It is always the forbidden pleasures that satisfy the very deepest urges, and the journey into Berghain’s abyss is laced with deviant exploration from the start. Lying like a dark secret at the end of dusty, fence-enclosed road, its huge looming face is as foreboding as the militant rhythms that have become associated with peak-time Berghain.”36 Urban exploration and hedonistic experimentation merge in the figure of Berghain as underground, industrial labyrinth.

The major clubs of the new club mile, including Berghain, demonstrate, however, a new spirit in Berlin techno. The clubs are “design-intensive” (Krims, xxix) in ways that carefully evoke the industrial underground of former times. Legal structures, long rental contracts, and a set clubbing routine now exist, but the aura of illegal parties is maintained through design. Their location in the former East — especially the symbol of industrial otherness that the Friedrichshain district still offers as compared to Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg — allows for a carefully constructed experience of clubbing as Ostalgie (nostalgia for the East), the pleasure of Eastern socialism as a failed system that, precisely in its failure of urban renewal, left open and public places and the potential for imagining new social formations. This well-financed club scene, however, continues to be confronted with new challenges. Four major clubs in the Friedrichshain district — Ostgut, Casino, Maria, and Notrox — were closed in one fell swoop in 2003 to make way for investors of various types, especially the 02-World that looms like a massive pop-capital sore over the Friedrichshain district. Tresor, one of the world’s most influential techno clubs and Berlin’s longest lasting club, was forced to move in 2005. The “urban renewal” project called Media-Spree is a further threat. While many of these clubs have found new locations, the challenge of maintaining affordable spaces proves daunting every year.

Amidst these local woes, the excitement of change in Berlin, with its iconic skyline of cranes, is now largely past. The city has more generally morphed into a place marked by lounge entertainment and relaxation, as indicated by the current dominance of the slower and reserved minimal/electro styles of EDM and the Prenzlauer Berg scene. With the rapid, design intensive development of Prenzlauer Berg, the notion of techno as a lifestyle is represented in the magazine De:Bug — itself a “design intensive” magazine based in this district. Its subtitle is indicative: “Magazine for Electronic Aspects of Life: Music, Media, Culture, Self-Control.” With the move of minimal and electro stars to Berlin since the turn of the millennium — including Ricardo Villalobos, DJ Hell, and Ritchie Hawtin — this scene has been given an enormous push. Since the departure of the Love Parade, minimal/electro can arguably be called the most definitive “Berlin sound”; though since much of minimal and electro was originally pushed by the Kompakt label of Cologne, one might claim this yet another media import from Cologne to Berlin — joining VIVA, popcomm, and many others. This time the import takes literal musical form. Cologne was the center for German pop media and music until 2000, when many of its major companies moved to Berlin. However, the transfer of pop media to Berlin has not signaled a corresponding rebirth in pop techno. In fact, the dissolving of the Low Spirit label has meant that the traditions of pop techno and megaraves have been further distanced from Berlin, now taking place primarily in western Germany and dominated by the organization I-Motion.

Nevertheless, the Berlin techno scene remains active and in some ways just as international, if not more so. Electronic music artists have flocked to Berlin because of its cheap rents and music/media networks. The woes of Berlin businesses have meant benefits for the global underground. However, much of the anticipation of what Berlin could become has now subsided. 2007 seems to have been the fateful year for the end of the era of change and anticipation; the move of the Love Parade that year coincided with both DaimlerChrysler and Sony announcing plans to sell their centers at another symbol of reunified Berlin, Potsdamer Platz, an ominous sign that Berlin will not become the world metropolis and financial center of Europe as was once imagined. To be sure, the fascination of Berlin hype often clouds the fact that Berlin is not quite the metropolis it is made out to be. Greater Berlin makes up only 4% of Germany’s population, versus greater London and Paris, which make up 14% and 19% of their countries’ populations, respectively. Its current status as a metropolis remains severely limited by Germany’s established tradition of federalism and dispersed, regional city centers: the port center is in Hamburg; the fashion and industrial centers are in Düsseldorf and the Ruhr Valley; the travel and financial centers are in Frankfurt am Main; and so on. How the city will cope with these challenges remains to be seen. However, its state as the perpetually broke anti-metropolis will continue to allow for new cultural possibilities that properly financed metropolises do not yield.

Indeed, in this anti-metropolis, pockets of dissonance and rebellion continue to emerge. Most interestingly, since the Love Parade has now left, the Fuck Parade is the only techno parade that remains. One might say it has even bizarrely achieved a sort of victory as the only parade left standing. As a symbol of the Berlin hardcore scene, the parade continues to protest annually, while Berlin cleans up and makes room for global capital. The Fuck Parade has even had its share of media successes; for example, it was the setting for one of the biggest YouTube sensations of recent times: The Techno Viking. A man who looked like a Viking with big pecs, firm abs, a paramilitary outfit, and a commanding attitude, and who just happened to love dancing to techno, was filmed at the 2000 Fuck Parade. The various postings on YouTube that followed have received more than 8,000,000 hits to date, with numerous spin-offs and a resulting fan page — www.technoviking.tv. In another context, the riots that occurred during Atari Teenage Riot’s performance at the 1999 Berlin May Day protests have achieved a degree of YouTube celebrity, with over 500,000 hits. The YouTube celebrity of these hardcore scene events reflects the enormous draw that Berlin city life and EDM can have.

Internationally, the effects of the Berlin history of the Love Parade continue to reverberate. The parade pioneered a new form of postmodern carnival with a science fiction inflection — a site where dance, technology, futurism, hedonism, and urban, military, national, and world histories collide. In addition, the parade could be viewed as a late manifestation (or culmination) of repetitive music culture since the genre’s popular rise, beginning with disco. Indeed, 1999 most likely saw the biggest party of repetitive music the world will ever see. Its name and its party form have spread throughout the world and inspired numerous similar events within the media circuits of urban life.

Within Germany, the Love Parade has embarked on a new era as a traveling carnival. This new dynamism and future have been paid for with a solidifying of power in the hands of McFit. Though still titled the “Love Parade,” this is only in name; its tacit title, like a stadium renamed for corporate sponsorship, is the McFit Parade. But despite these changes and despite the annual predictions of demise, the Love Parade continues to forge on and remain a formidable event, drawing music stars and tourists from Germany and around the world. This year the Love Parade celebrates its twentieth anniversary. Where it will go from here, and if it will ever return to Berlin to mark another phase of the capital’s development, is left for the future to decide.

***

Notes and acknowledgments:

All translations are my own unless otherwise indicated. Many thanks to Richard Leppert (Professor), Rembert Hüser (Associate Professor), Christian Haines (PhD Candidate), and Emily Lechner (B.A. Summa Cum Laude) for their careful readings of various drafts of this paper. Many thanks to Ben Lukas Boysen, Marcel Weber, Prof. Todd Presner, and Hypercities.com for media assistance. Two scholarships made much of this research possible: first, a scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), with sponsorship from Peter Wicke and the Centre for Popular Music Research at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin; and second, a grant from the Berlin Program for Advanced German and European Studies with funds provided by the Freie Universität Berlin. Finally, my deepest thanks to my colleagues at das Archiv der Jugendkulturen (The Archive of Youth Cultures) in Berlin; the archive provided many of the research materials that made this article possible. The conclusions, opinions, and other statements in this publication are the author’s and not necessarily those of his friends, colleagues, and/or sponsoring institutions.

***

Sean Nye is a PhD student in the Comparative Studies in Discourse and Society program at the University of Minnesota, pursuing minors in music and German. His doctoral thesis concerns constructions of German identity in popular electronic music from Krautrock to techno. Research foci include Theodor W. Adorno, electronic and Goth-industrial music, philosophical aesthetics of music, subcultural studies, and intermedial studies of music, literature, and film. Nye has received fellowships from the Fulbright program, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), and the Berlin Program for Advanced German and European Studies. He has published reviews and articles in a variety of journals and independent media, including Cultural Critique and Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music, and he has worked as a translator of articles by Rolf Tiedemann and Karl Heinz Bohrer.

***

Works Cited

Books and Articles

Attali, Jacques. Noise. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

Belser, Alexander. X-Sample: Love Parade — Kulturwissenschaftliche Beobachtungen zu Techno, Pop und Rave. Hamburg: art & communication Verlag, 1999.

Bey, Hakim. T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 1991.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Borneman, John and Stefan Senders, “Politics without a Head: Is the ‘Love Parade’ a New Form of Political Identification?” in Cultural Anthropology. Volume 15, Number 2 (May 2000). Ed. Daniel A Segal. Arlington: American Anthropological Association.

Butler, Mark. Unlocking the Groove: Rhythm, Meter and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006.

Fatone, Gina. “We Thank the Technology Goddess for Giving Us the Ability to Rave: Gamelan, Techno-Primitivism, and the San Francisco Rave Scene” in Echo: A Music-Centered Journal. Volume III, issue 1 (Spring 2001). http://www.echo.ucla.edu/Volume3-Issue1/fatone/fatone1.html.

Fink, Robert. Repeating Ourselves: American Minimal Music as Cultural Practice. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

Garcia, Luis-Manuel. “On and On: Rhythm as Process and Pleasure in Electronic Dance Music.” Music Theory Online. Volume 11, Number 4 (October 2005). Society for Music Theory. http://mto.societymusictheory.org/issues/mto.05.11.4/mto.05.11.4.garcia.html.

Goetz, Rainald. Celebration. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1999.

_____. Rave. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1998.

Hitzler, Ronald and Michaele Pfadenhauer, eds. Techno-Soziologie: Erkundungen einer Jugendkultur. Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 2001.

Johnston, Lynda. Queering Tourism: Paradoxical Performances of Gay Pride Parades. New York and Oxon: Routledge, 2005.

Klein, Gabriele. Electronic Vibration: Pop Kultur Theorie. Hamburg: Rogner & Bernhard, 1999.

Krims, Adam. Music and Urban Geography. New York and Oxon: Routledge, 2007.

Mertens, Wim. American Minimal Music: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass. Trans. J. Hautekiet. London: Kahn & Averill, 1983.

Muri, Gabriela. Aufbruch ins Wunderland? Ethnographische Recherchen in Zürcher Technoszenen 1988-1998. Zürich: Zürcher Beitäge zur Alltagskultur 8, 1999.

Rapp, Tobias. Lost and Sound: Berlin, Techno und der Easyjetset. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2009.

Reynolds, Simon. Energy Flash: A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture. London: Picador, 1998, 2008.

Reynolds, Simon. Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. New York: Routledge, 1998.

Thornton, Sarah. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Hanover and London: Wesleyan University Press, 1996.

Westbam. Mix, Cuts & Scratches: mit Rainald Goetz. Berlin: Merve Verlag, 1997.

Wiechmann, Peer. “Love Parade 2000 — Brot und Spiele für das Volk?” in Journal der Jugendkulturen. Volume 2 (June 2000). Bad Tölz: Thomas Tilsner, 2000. 10–15.

Worthington, Andy. Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion. Loughborough, UK: Alternative Albion, 2004.

Visual Materials

be.Angeled. Dir. Roman Kuhn. Perf. Mark Spoon and Lexy. 2001. DVD. Universum Film GmbH, 2001.

Berlin: Symphony of a Great City. Dir. Walter Ruttmann. 1927. DVD. Image Entertainment, 1999.

Groove. Dir. Greg Harrison. 2000. DVD. Sony Pictures, 2000.

Human Traffic. Dir. Justin Kerrigan. 1999. DVD. Miramax, 2000.

Love is the Message — The Parade Documentary. VHS. Studio K7, 1995.

Loveparade: Masses in Motion. DVD. BMG, Ariola Media Gmbh, 2003.

Run Lola Run. Dir. Tom Tykwer. 1998. DVD. Sony Pictures, 2008.

Techno City: Ein Wochenende in der Berliner Szene. Dir. Joachim Haupt. SFB, 1993.

Trainspotting. Dir. Danny Boyle. 1996. DVD. Miramax Home Entertainment, 2004.

We Call It Techno: A Documentary about Germany’s Early Techno Scene and Culture. Dir. Maren Sextro and Holger Wick. DVD. Sense Music and Media, 2008.

Selected Discography

Alec Empire. Generation Star Wars. Mille Plateaux MP CD 11, 1994.

Atari Teenage Riot. Burn, Berlin, Burn! Grand Royal GR042, 1997.

Da Hool. Meet Her at the Love Parade. B-Sides #005, 1997.

Einstürzende Neubauten. Kollabs. Zick Zack ZZ 65, 1981.

Ellen Allien. Stadtkind. Bpitch Control BPC 021 CD, 2001.Various. be.Angeled: Original Soundtrack. Modul 74321 86511 2, 2001.

Various. Loveparade: The Anthems. Kontor Records 0191092KON, 2008.

Online References

www.de-bug.de

www.drmotte.de

www.ellenallien.de

www.fuckparade.org

www.groove.de

www.lexykpaul.eu

www.loveparade.net

www.mark-spoon.com

www.mijkvandijk.de

www.schlagermove.de

www.streetparade.ch

www.tanith.org

www.techno.de

www.technoviking.tv

www.westbam.de

www.wollexdp.info

New Berlin Club Mile – websites:

www.berghain.de

www.clubmaria.de

www.tresorberlin.de

www.raw-tempel.de

www.water-gate.de

www.week-end-berlin.de

- Matthias Roeingh, aka Dr.

Figure 2: Matthias Roeingh, aka Dr. Motte Motte, is a Berlin DJ primarily connected to the punk and acid house movements of the eighties. He provided the original idea for a parade in 1989. From its inception, he has been the spiritual “Father of the Parade,” usually playing the final set at the Love Parade and giving the only parade speech each year. Maximilian Lenz (Westbam) grew up in Münster but has been connected to the Berlin scene since the mid-Eighties; he has also been the main “star power” behind the parade. His Berlin label, Low Spirit Recordings, was the driving organizational and economic force in the parade organization: holding the rights to produce the Love Parade compilations and Love Parade anthem from 1996 until 2006. Dr.