The “crisis of Jewish identity” that will concern us here has two somewhat distinct frames of reference, involving musical enactments and rationales on the one hand, and a set of issues revolving around reception and interpretation on the other. The crisis in question, whose working out we will attempt to trace in Mahler’s music, is at once Mahler’s crisis and the more broadly experienced crisis of Jewish identity that his struggle has come, through historical circumstances, to represent in part and in nuce. If our topic is thus as broadly conceived as our title indicates, our discussion will eventually be brought to a much narrower focus through close readings of pivotal movements from his first two symphonies.

The case of Gustav Mahler has always held great interest for those seeking to delineate the troubled relationships between Jews and the anti-Semitic cultures—particularly Germanic cultures—within which they have lived and worked; this interest has, if anything, become more intense in recent years. The turn of the century in Vienna—Mahler’s Vienna—was especially fraught, marked by the precipitous decline of Austrian liberalism and the emergence of many Jews to cultural prominence against an anti-Semitic background that was becoming increasingly virulent. Among the most important of these was Mahler’s contemporary Freud, who became prominent in Vienna around the same time and, like Mahler, made substantial and lasting contributions to Austro-Germanic culture; the many striking parallels between the two go to the heart of the issues involved with Jewish representation within that culture more broadly. Like Freud, Mahler tended to extrapolate from his own complex experiences—of self, of family, of society—to project a vision of what it means to be human that has sometimes seemed to be more idiosyncratic than universal, offering an easy target to anyone who wanted to argue for his essential foreignness. And, like Freud, in contributing so forcefully to Germanic culture, Mahler became in turn a significant part of what that culture offered the world at large, attaining a position sufficiently eminent that attack was virtually inevitable.1

Mahler famously articulated his own position in the world as “thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, as a Jew throughout the world—always an intruder, never welcomed” (Alma Mahler, Memories and Letters 109; original; see map). We might suppose this statement to be somewhat exaggerated, since it functions both as a complaint and as a claim of authenticity for someone aspiring to be a Romantic Artist, but when we consider the reality of Mahler’s historical situation, it seems almost mild. Mahler was throughout his adult life indeed regarded as an intruding outsider, and precisely along the lines he indicates. Within Germanic culture, he was but an Austrian, and being an Austrian in Germany was not exactly an honor in the decades following their humiliating defeat by the Prussians in 1866.2 And if that weren’t bad enough, he was actually not quite even an Austrian, since he was from the Bohemian provinces. And if that weren’t bad enough, he was a Jew, and it would have been hard to top that as a disadvantage in Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century, for this was an historical moment when putting together the words “homeless,” “Jew,” and “never welcomed” could never have seemed more appropriate.

As a boy in Iglau, Moravia, Mahler had enjoyed a social environment that tended to disregard his specific ethnic background—in part, to be sure, because Mahler’s family belonged to a partially assimilated German community ascendant within Iglau. His move to Vienna in 1875, however, placed him in a strikingly different environment, which he would never really escape. The cultural climate of capitalist liberalism that had once allowed Jews and middle-class Austrians a powerful position in society was in the process of crumbling away, and new social groups—urban artisans and workers, Slavs, and anti-Semitic Christian Socialists—were quickly rising to power.3 Viennese Jews found themselves in a society that was quickly and forcefully turning against them. Nationalist groups (the pan-Germanist faction and Christian Socialist Party), university circles, and especially the Catholic Church began to distribute anti-Semitic literature, some of it written by Catholic priests, including the pamphlets “The Talmudic Jew” (1871) and “A Ritual Murder Proven” (1893). By 1900, anti-Semitism in Vienna had become, as Jacques Le Rider claims, “a virtual obsession” (Rider, Modernity 195).4

Events conspired to make Mahler’s position as a cultural intruder particularly poignant. In 1897, he returned to Austria from Hamburg in what should have been triumph, ready to assume the most prestigious musical positions then available, as director of the Vienna State Opera and conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic. But there was a price he had to pay: to “qualify” for such lofty positions in Imperial Vienna, Mahler had to be willing officially to renounce his Jewish heritage and become Catholic—which he did readily, without apparent qualms. In other circumstances, this might have meant little more than a kind of all-too-familiar political compromise, except that in that same year, Mahler’s act of renunciation was rendered more significant by two events. In Vienna itself—corresponding, perhaps, to the “never welcomed” part of Mahler’s remonstration—Karl Lueger, head of the Christian Socialist Party, became mayor after having allied himself with the anti-Semitic faction headed by Georg von Schönerer. To place that event in historical context, we may note that Lueger and Schönerer would serve for a time as Hitler’s role models when he, too, came to Vienna some years later; specifically, these two prominent anti-Semites provided the future Reichsführer with a powerful demonstration of how politically potent an outspoken anti-Semitism could be, a lesson Hitler absorbed as part of a decidedly informal course of instruction that would include as well Mahler’s inspiring performances of Wagner.5

Meanwhile, in Switzerland—and this is the “homeless” part—Theodor Herzl, Viennese correspondent and exact contemporary of Mahler, led the first Zionist World Congress. Established in the aftermath of the Dreyfus affair in France, the Congress committed itself to establish a genuine Jewish homeland and thereby rescue the “never welcomed” Jew from being—in a quite literal sense—“homeless.”6 Yet, among the greater population of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, these historically significant events were overshadowed over the course of the next two years by an event even more newsworthy: the blood libel trial of the Bohemian Jew Leopold Hilsner, who was convicted in 1898 of the ritual murder of a nineteen-year-old Christian girl despite his manifest innocence and the strenuous legal efforts made on his behalf; in the wake of the initial verdict (which was confirmed a year later, although the sentence was commuted by Emperor Franz Joseph), there were widespread anti-Semitic riots throughout the eastern reaches of the empire, and Mahler himself was hissed at the podium and subjected to repeated attacks in the press.7 “poor, isolated being is overwhelmed by him” and listens as he describes the Jews as “a damned race, who see it as their pious undertaking to spill Christian blood, in order to dampen the dough for the unleavened Easter bread” (The Case of Sigmund Freud 208–210). Cf. Wistrich’s startling observation, which has even more direct relevance to Mahler’s tenure in Vienna, that “between 1898 and 1905 alone, there were no less than thirty blood libels recorded in different parts of the Empire, especially in the rural Slavic (and Catholic) regions of Galicia, Bohemia, Moravia” (339).]

Over the past century, Mahler’s contested cultural identity has shaped the reception of his music and his legacy more generally, intertwining issues of race, religious conviction and affiliation, and the meanings we ascribe to music and its creators; we need here cite only a few signal events of this extended narrative. Mahler, like many other prominent figures of Jewish heritage, was systematically purged from Germanic culture during the years of the Third Reich. In Freud’s and many another’s case, books were burned; in Mahler’s case, Mahlerstraße in Vienna was renamed and his music disappeared from the concert hall. As a victim of this kind of posthumous treatment, Mahler subsequently became a particular cause célèbre for many Jewish musicians—most prominently Leonard Bernstein, who made it his personal mission to restore Mahler to a prominent position in our concert halls, record shelves, and music-history texts (with the scarcely coincidental side effect that Bernstein himself acquired some of Mahler’s mystique, as a flamboyant, impossibly handsome, intellectual, Jewish conductor-composer—in effect, Bernstein built his own legitimacy as a serious conductor around his identification with Mahler).8 Clearly, the mission to rescue Mahler has succeeded; only Beethoven has more currency in today’s concert halls than Mahler, a circumstance utterly unimaginable fifty years ago.

But Mahler would seem to be somewhat tainted as an icon of Jewishness. Even if we disregard the issue of his official conversion to Christianity, which was surely in some part a matter of political convenience,9 work and its deepening intellectual and political orientation” (17). A telling anecdote recounted by Magnus Dawison (Davidsohn), a future Berlin cantor who sang in Mahler’s 1899 productions of Beethoven’s Ninth and Wagner’s Lohengrin, implies that the basis of Mahler’s conversion rested on his belief that one had to renounce a narrow musical practice in order to embrace a wider one, even as it poignantly reveals a continued, largely untapped connection to what he had renounced. Thus, after hearing of Dawison’s cantorial ambitions, Mahler replied, “But then you would have been lost to the world of art!”; yet he was soon improvising on remembered synagogue melodies for a spellbound Dawison (La Grange, Gustav Mahler 172–174).] his music documents a process of religious assimilation that predated that event by at least a decade. Each of his first four symphonies, for example, centrally and overtly addresses a Christian theme, and it is significant that the first three of these, along with the most explicitly Christian movement in the Fourth, were already written before his conversion and return to Vienna. Specifically, the First Symphony ends with a triumphant “breakthrough” chorale based fairly obviously on Handel’s Messiah; (link to example 1) the final two movements of his Second Symphony project the resurrection and absolution of a penitent; the Third Symphony miraculously marries, in the span of two song-movements just before the finale, the atheistic (and, according to some, anti-Semitic) Nietzsche with a setting of a folk poem celebrating the divinely forgiving grace of Jesus Christ; (link to example 2)10 and the finale of the Fourth Symphony, if somewhat ambiguously, presents a decidedly Christian child’s arrival in heaven. Even if some of us might insist that these works do not in themselves display specific religious affiliation and meaning—a claim that would surely have to ignore their texts, contexts, and musical referentiality, in order to hew closely to a view of music as intrinsically “absolute”—it is clear enough that Mahler meant them as overt affirmations.

Nor can we quite squeeze Mahler into the controversial mold of a re-imagined Shostakovich, who is claimed to have hidden away private and sometimes not-so-private meanings within his music, meanings that flatly contradicted its outward and official celebration of the Soviet state and its leaders11—first because Mahler was under no apparent pressure to prove his Christianity in musical terms, that is, by composing overtly Christian music into his symphonies—and second because he so obviously means exactly what his music seems to be saying. However much they might have wanted to be, the anti-Semitic Lueger and Schönerer were not yet Stalin, and no Siberia loomed for Mahler, even if he did in effect resign himself to partial exile in New York City during his final years, an act that has been widely interpreted as a protest against his treatment in Vienna. No, this is a hook Mahler can’t be taken off of, for in countless ways, he simply turned his back on his Jewish heritage, however close some of his personal attachments might have remained and even if he didn’t seem to display the familiar profile of Jewish self-hatred. Thus, besides the apparent full-frontal embrace of Christianity that may be read in his first four symphonies, there were his unflagging devotion to Wagner and to the general cause of German nationalism, his gradual distancing from certain of his friends who seemed to his young wife Alma to be “too Jewish,” and his later specific denial when Alma confronted him with the ragged bustle of the Jewish quarter in New York City and asked him point blank, “Are these our brothers?” (Alma Mahler, Memories and Letters 162; original).12 To borrow the context of his adopted Christianity: even Simon Peter couldn’t have done better than that.

So why is it that many Jews today so proudly claim Mahler as one of theirs? Partly, it is because he actually “made it” as a composer, and it is an enormous achievement for a Jew to have succeeded within such a hostile cultural environment. And then, of course, compromises like the ones he made were simply necessary, and it would be ungallant to look too closely at the particulars. It is easy enough to say, and even to believe, that without the intense pressure to convert that figures such as Mahler felt, they would not have done so. Nor should we ignore Leonard Bernstein’s efforts to universalize the theme of resurrection in Mahler’s Second Symphony, performing it in November 1948 in Israel to mark the first season of the renamed Israel Philharmonic, performing it in November 1963 to express a world’s mourning after the assassination of the Catholic John F. Kennedy, and performing its final, most Christian movement, even as land mines continued to explode nearby, to celebrate the reopening of Mt. Scopus in Jerusalem after the Six-Day War in 1967—although we may note that he was not without opposition in any of these three instances, particularly with his attempted musical alchemy of converting the base metal of Mahler’s conversion to Christianity into a shining symbol of Jewish renewal (Page, 78–84, 240–250, 309–315). (One particular awkwardness was the German language of the original; the solution for the Mt. Scopus performance was to sing it in Hebrew—which, given this text, produces an almost surreal effect.) But, above all else, it is surely because the self-appointed guardians of Germanic musical culture have so often insisted on Mahler’s essential Jewishness, just as they had Mendelssohn’s. In fact, the parallel is in some particulars remarkably close; just as Wagner viciously attacked Mendelssohn in the year following his death, so would the anti-Semitic Rudolph Louis condemn Mahler just after his departure from Vienna, in an essay that would reach its third printing the year following Mahler’s death:

If Mahler’s music would speak Yiddish, it would be perhaps unintelligible to me. But it is repulsive to me because it acts Jewish. This is to say that it speaks musical German, but with an accent, with an inflection, and above all, with the gestures of an Eastern, all too Eastern Jew. So, even to those whom it does not offend directly, it cannot possibly communicate anything. One does not have to be repelled by Mahler’s artistic personality in order to realize the complete emptiness and vacuity of an art in which the spasm of an impotent mock-Titanism reduces itself to a frank gratification of common seamstress-like sentimentality. (188; original)13 Mahler, in seeking to escape his racial traits, ended by representing nothing so much as the Jew. For if there is anything visible behind the music of Mahler, it is the Jew as Wagner, say, describes him in ‘Das Judentum in der Musik,’ the Jew who through the superficial assimilation of the traits of the people among whom he is condemned to live, and through the suppression of his own nature, becomes sterile. … It is the Jew as he is when he wants most to cease being a Jew. (206–209, 215–216, and 220–221).” Notably, Rosenfeld is by no means anti-Semitic in conventional terms, for in the same volume he writes approvingly of Ernest Bloch, “one of the few Jewish composers [who is] really, fundamentally self-expressive” (287).]

In the wake of rebukes like this and the Nazi cultural purge a few decades later, human decency seems to require that Mahler be reclaimed as a Jew so that he does not simply remain homeless; to borrow once again from Christian lore, Mahler is in this sense a bit like the Prodigal Son who is honored all the more for having once gone astray.

But what if there is something to Louis’s claim that Mahler speaks musical German with a Jewish accent? Even if Louis meant that in the most negative way, couldn’t his claim, in the end, offer a sign that a part of Mahler resisted assimilation?—that however hard he worked at convincing himself he was a Christian and a German, he was in the end truly and fundamentally Jewish?—and that the kernel of his Jewishness that he could not or would not eradicate might serve as an emblem of sorts for the Jewish condition and struggle more broadly? That this might be true, or sensed to be true, may explain why Mahler is so readily accepted as, not just a Jew who made it as a composer, but also as, more specifically, a Jewish composer, a composer whose Jewishness mattered and continues to matter as a positive dimension of his musical personality. Bernstein certainly argued along these lines when he presented his view of Mahler as a “double-man,” and saw Mahler’s musical “neuroticism” as an expression of his Jewish temperament.14 But even if audiences ranging from the anti-Semitic Louis to today’s listeners can recognize or sense this element in Mahler’s music, it is no simple matter to identify it in a way that will seem satisfying, or that will pass muster within a musical culture that wants to believe that “serious” music should ideally aspire to a kind of universal language uninflected with cultural traces of this kind. The challenge, then, is not just to prove that Mahler’s music acts Jewish, but also to prove that its acting or being Jewish—or being anything in particular, for that matter, besides abstract patterns of sound—is not at odds with its being genuinely music.

Perhaps the most obvious way to make a plausible case for the Jewishness of Mahler’s music would be to focus on a passage that actually sounds Jewish to many who hear it—not German with a Jewish accent, but frankly and openly Jewish. In the funeral march (third movement) of the First Symphony, after the canonic, minor-mode version of “Bruder Martin” that opens the movement, we hear music that has struck many listeners as klezmer-like. This passage was, indeed, not only “Exhibit A” in Bernstein’s presentation of Mahler as a “double man,”15 but also the most likely point of reference for Louis’s vitriolic dismissal of Mahler, situated as it is within his “Titan” symphony and indulging what might well be taken, unsympathetically, as “seamstress-like sentimentality.” Both Carl Schorske and Theodor Adorno take note of the passage’s disruptive quality, drawing attention to the ability of this “raucous tune” to strip the funeral march of its earnestness (Schorske, Gustav Mahler 12), and hearing the disruption as an “unmediated contrast to the point of ambivalence between mourning and mockery” (Adorno 52). Indeed, the interpolation not only conflicts with the tone of the preceding canon, but also projects an internal conflict, between an overt sentimentality (already undercut through its own schmaltzy exaggeration) and the dance-band rhythms that twice interrupt it. But even apart from its affective, gestural qualities, the passage disrupts through its colloquial or popular style; it is music spoken with dialect, as Adorno suggests, perhaps as far as one can travel from the “learned” style of the canon that preceded it (link to example 3) (Adorno 23).

But is this passage Jewish? Although it has been taken to be overtly and obviously Jewish, it has also been heard as Hungarian or Bohemian, and many hotly deny that it is Jewish, or at least specifically Jewish. And it is eminently possible in performance to downplay its ethnic profile to a large extent, which some have elected to do (link to example 4). The issue is, after all, fraught with historical and emotional baggage. As Louis would have it, its Jewishness is involuntary, the result of Mahler’s attempt to pass himself off as German. And even if we find the Jewish quality deliberately contrived, we are—given the history of Mahler reception and the legacy of the Holocaust—understandably discomfited by its presence here as an intruding element, ostentatiously out of place. Perhaps, indeed, it is that we wish not or dare not to make sense of its Jewish character, for this line of inquiry is disturbingly tainted; we recoil from the pernicious essentialism of critics like Louis to the point that we hesitate to engage at all with the possibility of specifically Jewish elements in Mahler’s music. Nevertheless, a strong—if not definitive—case may be made for this music’s deliberately contrived Jewish profile, based solely on its technical features.

Most immediately striking is the instrumentation of the passage: after the Bruder Martin canon concludes, the reed instruments emerge into prominence, beginning with the oboe, and continuing with the E-flat clarinet accompanied by bass drum and high-hat cymbal.16 The choice of the E-flat clarinet in particular recalls the sound of Jewish klezmer bands, as the clarinet was perhaps the most easily identifiable “voice” in the ensemble (after usurping prominence from the violin in the early nineteenth century).17 Although the oboe is not normally associated with the klezmer band tradition, it does have an affinity to Eastern-European Jewish music, as it convincingly imitates the “sweet” or nasal quality cherished in the voice of the hazzan, or cantor.18 And lastly, the alternation of bass drum and cymbal hits underneath the clarinet melody provide the characteristic rhythmic “boom-chick-boom-chick” accompaniment found frequently in klezmer dance tunes, replicating as well the most common klezmer percussion ensemble (“puk”/“baraban” and “tats” in Yiddish).

The dotted march rhythm of the oboe melody replicates another characteristic trait of Eastern-European Jewish folk-music, a point emphasized by Max Brod when he argued that Mahler was indeed a composer of “Jewish melodies.”19 In fact, the predominance of this rhythm is well-illustrated by the only musical example given to illustrate Hassidic music in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Werner 642): this melody has the same rhythm as the one found in the oboe melody and, as in the oboe melody, it is repeated several times in succession (link to example 5).

What is finally striking about the oboe and E-flat clarinet melodies is the foregrounded interval of an augmented second, between B-flat and C-sharp. The resulting modal collection of these tunes, G–A–B-flat–C-sharp–D–E–F–G, has been variously identified as the “altered Dorian,” “Ukrainian Dorian,” and “Misheberakh” mode.20 Abraham Idelsohn has identified ways in which this mode functions in Eastern-European Jewish music traditions: melodies usually rise rather than fall, pivot around the third scale degree, emphasize the fourth and seventh scale degrees, and frequently feature an upward turn figure between the first and fifth scale degrees (1–2–3–4–5–4–3–2–1);21 Ex. 6, a Jewish tune carried across Eastern Europe in the early nineteenth-century by Polish synagogue singers, illustrates these traits (link to example 6). As may be noted, parallels between these characteristics and the oboe and E-flat clarinet melodies in the funeral march are quite striking.

To be sure, the altered Dorian mode also commonly occurs in folk songs of Romania and Hungary, which may explain why the oboe and clarinet melodies are frequently identified as having a “Hungarian” flavor.22 But the treatment of the mode in Hungarian and Romanian folk-music traditions is characterized by a modal wavering rarely found in Eastern-European Jewish music (Idelsohn, Jewish Music 191–2). A Romanian folk song from 1860 illustrates this wavering, as the fourth scale degree alternates between C-sharp and C-natural, and the third scale degree between B-flat and B-natural (link to example 7).

At the very least, then, this passage blends Jewish musical idioms with other Eastern European musics, and we may note that doing this much alone would seem to be a bold statement, an assertion that Jewish, Bohemian, Hungarian, Romanian, and Ukrainian musical styles (in rough descending order of the generally perceived “presence” of these elements) may plausibly join in the discourse of a symphony otherwise specifically grounded in the Austro-German tradition. But the statement the music makes is considerably more complex than this, and might well be read as an even stronger claim of musical and cultural viability.

The movement in question begins with one of the most notorious examples of Mahler’s penchant for grotesquerie: a funereal, minor-mode presentation of a familiar children’s tune whose words and sentiments seem wholly inappropriate, thus implicitly asking, “steh’ schon auf?”—“Are you sleeping?” in the well-known English version—at a funeral (hear Ex. 8). Early audiences were puzzled, even shocked by this movement, with its juxtaposition of a school-yard song with the topic of death, a situation exacerbated by Mahler’s refusal to provide extensive programmatic material for several early performances: Ferdinand Pfohl reported the music to be “strange, grotesque, and bizarre;” August Beer, after the Budapest premiere, characterized the funeral march as having “a note of parody that…produces a thoroughly strange impression;” and the audiences of the Weimar and Berlin premieres, having received almost no prior programmatic explanation, found the grotesque death march entirely absurd (Floros 39) (link to example 8).

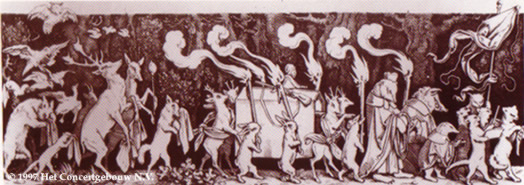

In the rather sketchy programs that Mahler did provide early on, this movement was titled “Todtenmarsch in ‘Callots Manier’” (or some close variant) and paired with the finale (“Dall’ Inferno al Paradiso”) to form “Commedia humana,” the second half of a larger, two-part structure for the symphony as a whole.23 Mahler’s purported inspiration for the piece—a woodcut, Des Jägers Leichenbegängnis (“The Hunter’s Funeral Procession”), by Moritz von Schwind (See Figure 1)—introduces a mode of cultural critique that informs the movement’s narrative. As Mahler writes in later program notes:

Funeral March “in the manner of Callot.” The following may serve as an explanation: The external stimulus for this piece of music came to the composer from the parodistic picture, known to all children in Austria, “The Hunter’s Funeral Procession,” from an old book of children’s fairy tales: the beasts of the forest accompany the dead woodsman’s coffin to the grave, with hares carrying a small banner, with a band of Bohemian musicians, in front, and the procession escorted by music-making cats, toads, crows, etc., with stags, roes, foxes, and other four-legged and feathered creatures of the forest in comic postures. At this point the piece is conceived as the expression of a mood now ironically merry, now weirdly brooding. (Mitchell 157–8; original)

The woodcut to which Mahler refers comically inverts the structure of power normally operating in the forest. Animals lead the body of a hunter toward his grave: the hunter and the hunted, the powerful and the powerless, have switched positions. Such satirical inversions of domination—carnivals, as Mikhail Bakhtin calls them—enact mock reversals of social power structures, temporarily liberating marginalized social groups from the prevailing truth of an oppressive social hierarchy (Bakhtin 1-58). Mahler, too, presents a carnivalesque inversion; moreover, the blended Jewish/Eastern-European music clarifies that the allegory has, in this movement, specific applications. The third movement uses the carnival to address the oppression of Vienna’s Jewish minority by its Catholic majority—as well as, perhaps, the Eastern lands under her dominion—constructing an inversion fantasy in which the culturally oppressed Jew (or Gypsy, or Slav, etc.) surmounts the powers of the dominant group.24

|

|

Moritz von Schwind, “The Hunter’s Funeral Procession”

|

Of course, such a narrative of confrontation and inversion requires the presence of both the oppressed and the oppressor; the latter, as it happens, has been hiding in plain sight all along, assuming the guise of a children’s round perversely transformed into a funeral march, against which Mahler has opposed the klezmer-like melody. “Bruder Martin (or Jakob), steh’ schon auf?;” “Frère Jacques, dormez vous?;” “Are you sleeping, Brother John?”—regardless of the language, the words of this song place it within a distinctly Catholic context, with the morning bells ringing (Matins), calling the Catholic faithful to prayer—even if a long familiarity with the song as an innocuous children’s round has today rendered its Catholic identity nearly invisible.25 Indeed, we may speculate that had this religious content been any more overt, Mahler could never have placed the movement before the public. And yet, despite the obliqueness of his presentation, we may also speculate that there may have been a sharper point to Mahler’s choice of this thematic basis for the funeral march; thus, the song most likely originated as a form of religious mockery (a legacy that Mahler might have either known or inferred), childishly taunting those left out of the Catholic service, be they Protestant (Bruder Martin Luther) or Jewish (Jakob).

The opposition of this Catholic-song/funeral-march to the klezmer-like music is stated with particular force late in the movement, when an attempt to combine them results in musical chaos. But their opposing characters are already obvious during their separate presentations in the first part of the movement, when each is allowed to inhabit its own musical space, for, in Mahler’s treatment, the two themes occupy a shared structure of inverted power relations. This movement (like much of Mahler’s music) has been explained as an example of “low art” intruding upon the “high art” of the stylized “Bruder Martin” canon.26 In his reading of Salome, Sander Gilman argues that Richard Strauss constructs a tension between the vulgar, unintelligible “cacophony” of the Jews with the highly stylized world of Salome and the firm diatonicism of Jochanaan. The “Jewish” music here contrasts just as sharply, and even disrespectfully, with the established tone of the movement. Mahler’s movement, however, is better understood as turning this construction on its head. Although the “Bruder Martin” melody assumes priority by carrying the markers of high art (i.e., imitative counterpoint), it is systematically undermined. The canon and the Catholicism it represents are but caricatures and effigies to be mocked within the carnival space, where the relations of power are inverted, where—as Bakhtin points out—the inversion is both signified by and celebrated through the deriding laughter of the once-marginalized.27 is ambivalent: it is gay, triumphant, and at the same time mocking and deriding. It asserts and denies, it buries and revives” (12).]

The movement begins with measured timpani strokes, establishing a funeral-march rhythm; even in this we may hear a kind of cheapening of the funeral topic, for the march rhythm has been reduced to a simplistic alternation, eschewing the more elevated rhythmic idiom of the funeral march in Beethoven’s Eroica (which Mahler would reproduce in later symphonies, specifically in the kleine Appell in the first movement of the Fourth and the use of this motive, on a grander scale, to open the Fifth; link to example 9).28,” is given in Hefling, “Mahler: Symphonies 1–4” 388.] After a muted double bass begins to play “Bruder Martin” in the minor mode, other instruments join in canonically in the lowest ends of their registers, at first at intervals of six measures, then at four, and eventually at two. The accelerated entry of instruments, along with the gradual increase in the number of instruments participating in the canon, implies an intensification, but a footnote at the beginning of the movement, “pianissimo ohne crescendo,” directs that the seemingly inevitable crescendo must not occur during the entire course of the canon. Rather, the restrained music must continue, impotent, along its monotonous course. Since, as noted, the canon aspires to the profundity of a serious funeral march from its incongruous origins in a children’s schoolyard song—well-known as one of the most banal canonic constructions on offer—the gross exaggeration of the funereal tone of the piece seems to reinforce the comic impossibility of this leap to expressive and emotive significance, evoked as it is through tediously low registers and dynamics (link to example 8 again).

After four instruments have joined the canon, an oboe enters with a sharp, punctuating counter-melody characterized by staccato notes and leaps of a fourth (mm. 19-23; link to example 10). The more specifically Jewish melody has yet to be introduced; however, the entrance of the oboe, which will later play that music, here foreshadows the conflict. Within the atmosphere of formality created by the canon’s funeral march, the oboe transforms the dotted rhythms of the concluding phrase of the funeral march into a lilting dance step, thus turning from a gesture of apparent respect to open jeering, so that it seems to dance flippantly alongside the ongoing march. The incompatibility of these conflicting sensibilities becomes even more explicit when the descending scale that concludes the dance figure shadows the canonic melody in mockingly dissonant parallel seconds, a paradigm of musically rendered laughter that is only partly muted by the layered presentation. Unlike Mahler’s more characteristically vital counterpoint, the canon remains static, undramatic and unimaginative, consistently mocked by the counter-melody that registers as its only claim to a more engaging musical profile.

The klezmer-like music, on the other hand, develops thematically and exhibits none of the tight constraints regarding tempo, rhythm, and affect that govern the opening march. This difference is especially marked when the two confront each other directly, later in the movement (hear Ex. 11): as the “Bruder Martin” canon continues to drone away as it has the entire movement, marked “still soft,” the klezmer-like melody transforms into a wild dance, marked “loud and extremely rhythmic” and, perhaps most telling, “with parody.” We have by this point in the movement long noted the irony of the funeral march, with its mock-serious mood. With this eruption, we may sense the exultation of the Jewish melody, moving from mockery to an overt trouncing of its oppressor (link to example 11).

But this reversal of power does not last. Ultimately, the third movement conforms to the final convention of the carnival: the carnival must end, and in Mahler’s piece, the canon speaks the final word. The carnival atmosphere that dominates the movement does not resolve the cultural oppression that Jews felt in fin-de-siècle Vienna. As Bakhtin notes, the laughter of the carnival is always also rendered self-mocking by the realization that the carnival is never really an escape from social conditions (257–261). Moreover, the movement yields directly to the anguished tones of the finale, which lead eventually to Mahler’s version of the “Hallelujah Chorus;” however we construe the projection of cultural inversion in the funeral march, it takes place within a larger scenario of Christian salvation. Thus, while the funeral-march movement has much to tell us about how Mahler positioned himself within a Christian/Jewish cultural conflict—of which, more later—its carnivalesque inversions do not translate simply into a celebration of Jewishness.

There are, to be sure, other ways to make a case for the Jewishness of Mahler’s music, ways that already have some currency and may be extended easily enough. It has been pointed out, for example, how different Mahler’s version of Christianity is from Catholicism or any other widely accepted version of Christianity. Thus, his “Resurrection” Symphony places much more emphasis on heavenly grace and forgiveness than anything one is likely to hear in a church, deftly putting aside the very idea of judgment even though what is ostensibly being redeemed, according to earlier movements, is the soul of a rather self-centered suicide victim who was probably also an unrepentant adulterer.29 We may note, as well, the rather bizarre way that his Third Symphony seeks to “derive” Christianity through a process of evolution within an idiosyncratic version of the cosmos, transporting us from inanimate nature, through flowers, creatures of the forest, and even Nietzsche, before supplanting it all with another singularly non-judgmental version of heavenly grace. And if one listens carefully to the words in the finale of the Fourth Symphony—a movement he at one point subtitled “Heavenly Life,” and which presents a child’s view of heaven in the style of a lullaby—one notices that even Herod is apparently redeemed in this supposedly Christian heaven. Moreover, his redemption does not seem even to involve reform, let alone contrition, as he stands cheerfully ready to slaughter the Lamb—which can only represent either Christ or the countless children that the historical Herod slaughtered, and which is led in by no less than John the Baptist, another of Herod’s victims. Yet, however strange these highly individual takes on Christianity may be, it is hard to see them as particularly Jewish, particularly as an aggregate, except perhaps in their generalized rejection of Christian orthodoxy. And it seems particularly odd to find Mahler setting—in the finale of the Fourth Symphony, the first major work he composed after his return to Vienna—a text that reads, “We lead a meek, innocent, little lamb to its death!” (original)—just as if the blood libel and the charge of being Christ-killers were by then a thing of the past.

What may work better here, if we want to get at Louis’s claim that Mahler “spoke musical German with an accent,” that his music “acts Jewish,” is for us to think briefly about the model of language, and about what typically happens when a great writer writes in a language not his or her own. For instance, we may consider Nabokov, whose mastery of English was of the highest order, but who wrote like no native speaker would. What matters here is a sense of being inside or outside the language; a strong writer will always have an individual voice, but if she or he is a native speaker, there will usually be some sense of familiarity as well. With Nabokov, though, there are always going to be moments when you realize that his experience of English is different from yours, that his engagement with the language is that of an outsider, however well he has mastered it, however much he seems to love its sound, its nuances, and what it can do for him. Word choice will suddenly seem to have the subtlety and strangeness of a butterfly looked at from up close, and your own language will seem for a moment foreign to you.30 So, too, might Mahler’s music sometimes seem Germanic without seeming precisely German. One way it might do so is through the exaggerated nuances of his orchestration. Another might be the frequent and unsettling shifts, as if the music can’t seem to steer as straight a course, or maintain the same sense of musical flow, as a symphony from another, more “German” composer—and here, we might remember Bernstein’s identification of a neurotic element in Mahler’s music. These things, indeed, could easily have been what Louis meant when he wrote that Mahler’s music exhibited the “gestures of an Eastern, all too Eastern Jew,” especially when we remember that Mahler’s conducting—particularly his conducting of Beethoven, and most particularly of Beethoven’s Ninth—was criticized for a similar kind of “Jewish” gesturing, both in the fussiness of the sound itself and in his elaborately gestural manner on the podium, which was much discussed and even caricatured in the press (see Figure 2).31 (And here, again, we might think of Leonard Bernstein for a more modern example of something similar—and someone similarly vilified in the press.)

|

|

Figure 2: Mahler Conducting, Silhouettes by Otto Bohler |

But the most fruitful way to get at the question of Mahler’s musical Jewishness is surely to consider more specifically the nature and perception of German music in the late nineteenth century—the ideal that Louis claimed Mahler’s music did not attain—and then to examine instances when Mahler engages directly with that ideal. What emerges when we look from this vantage point at the wide variety of situations that Mahler creates in his music, is that he sometimes speaks fluent musical German—from the inside, as it were—but also at times presents a distorted version of that ideal, one whose oppressiveness is staunchly resisted. We find in these two types of situation the essence of what it meant to Mahler to be a Jewish composer within late-nineteenth-century Germanic musical culture. German music was at that time self-consciously the most elevated music, intellectually and spiritually demanding, with an unrivaled capacity for powerful and exalted expression. Whether or not one agreed with the German philosophers who claimed that music was the highest of the arts—implicitly, of course, they meant German music, which was to say, music at its best—musical German was eminently a language worth mastering. Yet the elevation of music to this position in Germanic culture involved a strong component of oppression, and was inflected by a correspondingly strong dose of German nationalist feeling. German music was elevated—and many were quite explicit about this in the generation following Beethoven—because Germans were more capable than others of this kind of profound engagement with what was claimed to be the highest of the arts, and less disposed towards the kind of frivolousness one found, say, in Italian music (Pederson 87–107). Listening to Beethoven and Bach was good for you; it made you better Germans. And we may well note that this rather oppressive attitude, passionately fostered throughout the nineteenth century as an essential component of German nationalism, is still very much with us in the exaggerated reverence we are taught to bring to the concert hall, except now we pretend it’s a universal language, so we drop the “German;” now we say: listening to serious music—such as Bach and Beethoven—is good for us; it makes us better people. In this way was born the myth of musical transcendence, that German art music—the musical “mainstream”—was universal and culturally uninflected, a myth that has occupied the background for most attempts to identify Jewishness (or Czechness, or Russianness, or any other implicitly marginalized ethnicity) in music.

Americans, especially, have long had something like Mahler’s ambivalence regarding what we now call “classical” music (which is mostly German, or German-derived, but no longer exclusively German); for us, though, “popular” musics (jazz, rock, Broadway, whatever) serve as the less serious alternative. Broadly speaking, as a culture, we tend to have something like reverence for the classical tradition—although this is less and less true—but feel more at ease with some flavor of popular music, which is another way of saying that, while we revere classical music, we are also oppressed by it. And we can find ready examples of this kind of ambivalence, with “popular” musicians such as Duke Ellington and more recently Paul McCartney aspiring to write for the concert hall, but also using “classical” music as a point of reference—what musicologists like to call a “topic”—for something much less positive. An early and well-known example of this use of a classical-music “topic” from McCartney is the 1966 Beatles song “Eleanor Rigby,” which is dominated by the sound of closely miked lower strings playing in an agitated minor mode and in a contrapuntal texture evocative of Baroque music (not a sound typically used in popular music before this song); this is “classical” music at its most severe, emerging most prominently during the opening and recurring phrase, “Ah, look at all the lonely people,” which seems almost to point to this music (link to example 12). Here, a referential version of “classical” music serves to represent a kind of alienation, a sense of lonely isolation; notice, for example, how little heed this relentless churning motion pays to the sympathetic vocals, which seem powerless to actually connect with the lonely people, forever trapped within the unstoppable flow of their empty busy-ness. Later, in the verse about Father McKenzie—it was originally going to be Father McCartney, but that’s another story, and much too Freudian for us to get into here—the theme of failed communication leading to alienation is made particularly clear, as we find Father McKenzie “writing the words of a sermon that no-one will hear” (link to example 13).32

Intriguingly, Mahler also wrote a song about a preacher whose sermons are not heard, and used a very similar technique. In Mahler’s “St. Anthony of Padua’s Fish-Sermon,” based on a folk poem from Des knaben Wunderhorn, St. Anthony leaves his empty church to preach to the fishes, who listen attentively, are most appreciative, and then go back to business as usual. In an explanation of the song, Mahler declared this to be a satire on humanity that he believed “only a few people will understand,”33 and he’s probably right. Most hear it as a satire on the way typical congregations listen appreciatively, but then return to their lives as if nothing has happened. But the song probes deeper than this, as Mahler indicates, for it also satirizes St. Anthony himself, who seems quite as content to have a congregation of appreciative, uncomprehending fish as he would have been had real people come to his church. And it satirizes the smug complacency with which we—that is, humanity at large—go through the motions of communication without anything whatever actually being communicated, beyond the roles themselves, of preacher and preached-to, etc. Thus, we are implicitly told, we have roles to play in relation to each other, but they are empty, without real content, and we don’t ever really connect—just as, in “Eleanor Rigby,” the sad inflections of the voice observe empathetically, but cannot reach “all the lonely people.” In Mahler’s “Fish-Sermon,” he sets the swimming motion of the fish in the orchestra, with the dry voice and manner of St. Anthony set in the angular vocal melody; in one deliciously grotesque passage for the E-flat Clarinet, we even hear the sermon as the fish must hear it, in Mahler’s words, “translated into their thoroughly tipsy-sounding language” (see endnote 34).

Even before he completed the song, Mahler started working on a more elaborate symphonic version, which eventually took its place as the third movement—the Scherzo—of his Second Symphony (the “Resurrection,” link to example 14). Here, the theme of alienation is even more relentlessly pursued, and the effect reaches beyond satire to genuine pathos. On the three occasions that Mahler provided an account of this movement, he describes the empty, bustling activity of life in various ways, with the first account being the most elaborate:

When you wake out of this sad dream, and must re-enter life, confused as it is, it happens easily that this always-stirring, never-resting, never-comprehensible pushing that is life becomes horrible to you, like the motion of dancing figures in a brightly-lit ballroom, into which you are peering from outside, in the dark night—from such a distance that you can not hear the music they dance to! Then life seems meaningless to you, like a horrible chimera, that you wrench yourself out of with a horrible cry of disgust. (Abbate 124, her emphasis removed, Mahler’s restored; original)34

The second and third movements are episodes from the life of the fallen hero. The Andante tells of his love. What I have expressed in the Scherzo I can only visualize as follows: when one watches a dance from a distance, without hearing the music, the revolving motions of the partners seem absurd and pointless because the key element, the rhythm, is lacking. Likewise, to someone who has lost himself and his happiness, the world seems distorted and mad, as if reflected in a concave mirror. The Scherzo ends with the appalling shriek of this tortured soul. (Bauer-Lechner 784–5; original)

The spirit of disbelief and negation has seized him. He is bewildered by the flood of apparitions and he loses his perception of childhood and the profound strength that love alone can give. He despairs both of himself and of God. The world and life begin to seem unreal. Utter disgust for all being and becoming seizes him in an iron grasp, torments him until he utters a cry of despair. (Alma Mahler, Erinnerungen und Briefe 268; and La Grange, Mahler 785; original)

In the first of these, the hero wakes from a “sad dream [the second movement], and must re-enter life, confused as it is, … an always-stirring, never-resting, never-comprehensible pushing that … becomes horrible, … like the motion of dancing figures in a brightly-lit ballroom.” While Mahler eventually drops the analogy to dancers dancing to unheard music, he consistently describes the effect as of something missing, something vitally important, something that might give meaning to life—the music, we might say, that ought to direct and accompany the “dancing figures” of living humanity; thus, in the second description, he continues, “likewise, to someone who has lost himself and his happiness, the world seems distorted and mad, as if reflected in a concave mirror,” and, in the third, “bewildered by the flood of apparitions … he loses his perception of childhood and the profound strength that love alone can give—he despairs both of himself and of God.” In all three descriptions, the horror finally proves too much, and the hero’s outraged revulsion leads him to utter “a horrible cry of disgust,” “a cry of despair,” “the appalling shriek of [a] tortured soul.”

About the specific source for the overall scenario of his Second Symphony, Mahler was a little vague, perhaps because his apparent literary source, at least in the first movement, hit too close to home in its depiction of an adulterous relationship. Bernstein’s universalized—perhaps also more humanistic—reading of the symphony finds it a work that expresses the resurrective capacity of the human spirit, with a specific focus on the living that Bernstein insisted on even when he played the work after Kennedy’s assassination. But the most plausible programmatic explanation for the work, one that accounts more honestly for what Mahler had to say about it, and for what it actually does as a piece of music involved with a particular programmatic trope, is one that recounts the anguish of a soul caught between Heaven and Hell, forced to wander the earth because his business among the living is not yet finished, who recounts and relives traumatic events in his life, revisiting what led him to suicide in the first movement, dreaming of a lost love in the second, and recoiling in disgust in the Scherzo, when, from the vantage point of a soul whose body no longer lives, he contemplates the empty pursuits of the living world (Hefling, “Mahler’s ‘Todtenfeier’”). In the end, in the “Resurrection” finale, the wandering soul enters Heaven and is forgiven. This overall scenario explains more specifically why, in the Scherzo, the “hero” cannot “hear the music” that the living “dance to.” And, more broadly, it bears an uncanny resemblance to the perspective of a Jew—more precisely, of Mahler himself—caught between two worlds, unable to leave the one behind, incapable of fully embracing the other in part because he fears he will not be welcome, and so is forced to wander the world without a home of his own, disgusted by the emptiness he sees around him. Moreover, it captures, in its projected suicide and its despairing aftermath, the predicament of a Jew who has renounced Judaism but has not received a Christian welcome (although, again, we may note that the work predates Mahler’s own conversion by several years). And, sadly, we can see more clearly why the resurrection Mahler details in the finale proves unexpectedly forgiving and non-judgmental; in the alternative world that Mahler creates for himself in the Second Symphony, the penitent is offered a blanket forgiveness, one that might absolve, as we may assume, even the most grievous “sin” of being born a Jew.

The basic material for the Scherzo, as adapted from the “Fish-Sermon” song, is manipulated so as to create the effect of something self-generating, something all embracing, more than a little seductive, but also repellent and oppressive; it is in effect a parody of Germanic, “absolute” music, with all the seemingly autonomous flow requisite of that tradition supporting a grotesquely rendered musical surface. It is important to underscore here that what nineteenth-century Germans were successfully marketing as the central, most distinctive characteristic of their music was coextensive with the neutral, supposedly universalized designation of “absolute” music.35 Thus, as part of the background for both this particular parodistic presentation and Louis’s disparaging claims against Mahler’s music, we must note that the standard to which Mahler was once found wanting, or tainted, stands as the pure, essentialized core of “good” music, while at the same time remaining deeply inflected with a German-nationalist sensibility. Through this marriage and the particularities of the tradition itself, a sense of autonomous flow is both the great strength of the German “absolute music” tradition and the source of its oppressiveness. If you are in alignment with that flow, you are empowered by it; if you are outside, it seems oblivious, self-contained, and more than a little threatening, for it runs over everything, absorbs everything and seems irresistible in its force. It was this capacity of Mahler’s parodistic Scherzo, to absorb anything and everything that comes under its gravitational pull, that Luciano Berio exploited in the version of the movement that he presents in his 1968 Sinfonia (honoring not only Martin Luther King, but also Leonard Bernstein, who so often performed the “Resurrection” Symphony); in Berio’s version a bewildering amount of verbal and quoted musical material appears and disappears within its myriad currents and eddies (link to example 15).36

A reading of Mahler’s Scherzo along these lines produces a scenario that may stand equally well for what Mahler describes in his three accounts of the movement, in the first instance; for Mahler’s situation as a Jew within Germanic culture in the second; and, in the third, for Mahler’s ambivalent attitude toward German music, which here is presented as autonomous and even a little seductive in its on-going perpetual motion—acting something like the hypnotist’s twirling sphere or methodically oscillating pendulum—but made repellent through the banality of its material and its occasional flights into grotesquerie. The dramatic trajectory falls roughly into three parts: 1) the near-seduction by what we might call the “absolute music” topic; 2) the attempted (but unsuccessful) escape from its absolutist flow, and; 3) the ultimate rejection of the “absolute music” topic through a purging orchestral scream.

The movement begins with a wake-up gesture, which is not in the song, a gesture that establishes the impulse and musical motive that will seem to generate the perpetual-motion material that thereafter dominates the movement, material that seemed in the song to represent the swimming motion of the fish. This opening gesture also marks that material as an intruder, establishing from the beginning of the movement an outsider’s perspective on its “absolutist” flow. In this first section, we hear both prominent tokens of satire (the grotesque E-flat-clarinet figure), and a striking demonstration of the absorptive capacity of absolute music, when the vocal melody finally shows up and, instead of dominating as in the song, is not even allowed to finish its phrase before simply being absorbed into the musical flow. This is the kind of absorption that will be resisted by the subjective center of the movement—the tortured soul, Mahler’s Jewishness, whatever we may take that center to be (link to example 16). In the next part of the movement, the first attempt at seduction, a suave dance-like music is suddenly resisted at the end of the passage, just before a return to the original material (link to example 17).

Now comes a kind of dialogue, in which Mahler first presents an intensification of the “absolute music” topic—involving fugal processes and the addition of a counter-melody along the way—followed by a violent resistance, much louder than the “absolute music” material and in a different key. This pattern happens twice, that is, with two fugal passages followed each time by violent resistance. Then, with the second violent passage comes part two of the scenario sketched above: the apparent escape, which is into a world fairly dripping with nostalgia, an evocation of small-town rusticity, with the trumpet choir playing with their bells up in the air and with exaggerated expressiveness. Harps accompany the trumpet choir, adding a sense of comforting benediction, punctuated by occasional bird-like trills. Almost unnoticed, though, the “absolute music” topic sneaks back in during the later stages, signaling that the escape is only apparent, another dream world from which we must awake (link to example 18).

The final subjective response to the “absolute music” topic comes in the later stages of the movement. Once again, the violent resistance follows on the heels of the dance-like episode, but this time the resistance is more forceful and definitive, culminating in a ferocious “scream.” What happens after the scream is especially noteworthy. Once again we seem to have opened before us a subjective space where the “absolute music” topic doesn’t intrude, but this time it is no nostalgic escape into the past, since we can still hear the “absolute music” topic churning away underneath it all. Now the oppressor is in the background; the subjective surface seems to have wrenched itself away from its influence (link to example 19). In musical terms—and also in cultural terms—something important is represented by the emetic purge of the orchestral scream. The scream articulates with uncompromising force an irrevocable gesture of denial, of refusing to take part. Thus, there remain no indicators of subjective dismay in the fairly brief concluding section of the movement, only a sense of psychic detachment, and of waiting.

But even here there is ambivalence, for the direction the symphony as a whole points to is diametrically opposed to the orientation of the musical and cultural markers in this movement. Within the program of the symphony, the haunted subjectivity of the Scherzo that rejects the empty bustle of living humanity is immediately displaced in the calm opening of the next movement by a much less troubled subjectivity, through the sound of a human voice entering without instrumental accompaniment, seeking and eventually finding Christian redemption. How evocative, in this context, is the grotesque bustle of the Scherzo of those streets in New York, whose chaotic Jewishness Mahler was to reject some years later? And yet—on the other hand—how much more vital is a reading that focuses on the act of a resisting outsider fighting against the tide of absorption into the dominant flow of a hostile culture? Isn’t that the essence of being Jewish in the German lands at the turn of the century?

Nor, really, is the situation so very different in the First Symphony, in which the cultural conflict of the funeral march detailed above gives way, in the finale (and again only after a purging orchestral scream; link to example 20) to an overt embrace of Christianity. Indeed, there is no better passage in Mahler to illustrate a parodistic application of the “absolute” music topic as it has been outlined here, nor to see it so indelibly stamped as Germanic, than in the “Bruder Martin” canon that opens the movement. In striking fashion, as well, that movement offers both an extended escape from the conflict that governs the movement more broadly, and a telling demonstration of the absorptive capacity of the “absolute” music topic. In the funeral march, as in the Scherzo of the Second Symphony, Mahler reserves a trio-like section for his most intensely subjective moment, offering a momentary escape from the cultural situation altogether in the form of an extended quotation from the final song of his Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, “Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz.” (link to example 21)37 The canonic droning and ominous D-minor character of the previous material subsides, and we are enveloped in a place of respite, with optimistic ascending melodic contours in G major. Opposing neither side of the already-stated conflict of the funeral march, the passage seems a moment apart from that conflict, independent even of perplexing issues regarding which of the projected antagonists—hunter or hunted, Catholic or Jew—is to be regarded most sympathetically.

The first movement of the symphony also quotes a Gesellen song, “Ging heut’ Morgen übers Feld,” the second in the cycle; significantly, the two songs frame the cycle’s psychological chronology, in that “Ging heut’ Morgen” confronts the present with a lost youthful exuberance and “Die zwei blauen Augen” ends with a projection of a future blissfully free from the pains of the present (i.e., within the sleep of death). “Die zwei blauen Augen” is oddly configured as a song, comprising three stages of decidedly different character, each in its own key and with its own characteristic motivic basis. Mahler sets these three stages with some degree of irony: while only the last stage overtly embraces death as an alternative, it is also the only one to offer sustained comfort, while the earlier stages, each in its turn, projects a funereal tone with a distinctive, obsessive motive derived from the general topic of funeral march.

Notably, these motives—repeated-note dotted figures and the slow, steady beat of the timpani, respectively (link to example 22)—are precisely those that most clearly mark the “Bruder Martin” canon as funereal. But there is a crucial difference in how they are treated in the symphonic movement, for the dotted figure has there been given an oddly nuanced secondary role, entering originally as part of a stately counterpoint to the ongoing “Bruder Martin” canon that then develops an untowardly festive lilt along the way, as noted (link to example 10 again). The ambivalent relationship between this counterpoint and the main theme is never adequately resolved; while all its central elements derive audibly from the “Bruder Martin” tune as Mahler presents it, including the dotted figure itself and the upper-fourth lick (which literally doubles the tympani strokes), it dances rather than marches, and seems to have more affinity with the klezmer-like music to come than with the Catholic “Bruder Martin” tune. Yet, in the conclusion of the movement, during the last bars of the funeral march proper, remnants of this tune are at least equal partners with, and seemingly fused to, “Bruder Martin,” the victim of the assimilative power of the “absolute music” topic (link to example 23).

Thus, however mocking the countermelody may be, it shadows the funeral march too closely to avoid getting caught up in its obsessively absolutist flow. In fact, its absorption into the march becomes so complete that, from the moment the counterpoint enters, its association with the funeral-march topic gradually becomes closer even than the “Bruder Martin” tune itself; unlike the latter, the dotted-figure counterpoint plays out, intact, with every recurrence of the topic. Even during the fragmented conclusion of the movement, the dotted-figure tune gets a full hearing; indeed, its mockery is by then so muted that it can simply substitute for the “Bruder Martin” tune, which, aside from the harp’s playing of the cadential bar in diminution, is not heard at all.38 Perhaps this can be construed as the triumph of the dance lick over the funeral march; given the more basic presence of the funeral-march topic, however, it seems more the reverse.39

The sense of subjectivity in the quoted episode stems from its separation from previously established realities, as in the song, but here the separation is based on memory rather than on the projection of an oblivious future within the dreamless sleep of death. Thus, the serenity of the opening part of the quotation, which clearly could not have come from anything we have heard thus far in the movement, betokens the intimacy and familiarity of a remembered past rather than a projected future. Then, in the second part of the quotation, with its sagging chromatic lines and “farewell” horn calls, the temporal status of this serenity—its pastness—is clarified, as is its relationship to the larger funereal setting. At the end of the quotation, when the dotted figure is recalled, it is inflected with a tone of mockery more pronounced than in the song, a foretaste of the return to the objective present and the funeral-march rhythms that immediately follow. Despite these critical differences, the song continues to “speak” in all of this, for serenity, pastness, intense subjectivity, leave-taking, even the exteriority of the dotted figure, are all present in some form during the third stage of the song, if sometimes in a kind of instrumental counterpoint to the words.

Structurally, too, Mahler exploits relationships already given in the song, but applies them toward somewhat different ends in the funeral movement. Built into the stages of the song is an implicit circularity, as the recollection of the fundamental motive from the first stage at the end of each of the later stages makes feasible (if only abstractly) all possible orderings of the three sections. In the song, this potential circularity is suggested for the sake of denying it; neither the “progressive” key scheme nor the psychological journey is in any way circular. Thus, the middle, more march-like section wrests us from the moribund first stage by shifting harmonically to a modally ambivalent flat-VI. The march topic here is both funereal and—in part because of the energizing harmonic shift at the opening, in part through the words—a manifestation of a journey undertaken with a sense of resignation and, perhaps, penitence (link to example 22 again). The recollection of the dotted figure at the end of the march already points to something left behind, and the subsequent stage confirms this as it settles into a comforting, major-mode subdominant specifically as an alternative to harmonic and psychological return.

Mahler borrows the latter move, to the major subdominant from the minor tonic, for the opening of the song-quotation in the funeral-march movement, converting what was a transport to a comforting oblivion into an escape to subjectivity and memory. At the end, however, he exploits the potential for circularity by borrowing, from the end of the first stage in the song, the move from dotted figure to timpani strokes, which enter in the flat-VI. Within the movement, this represents a structural thematic return, to be expected after a trio-like episode, but unexpectedly a half step removed from the tonic—just as, in the song, the concluding key is F minor after an opening in E minor.40 But here there is a much greater impact, since the tympani strokes in the funeral-march movement have been more centrally installed as a marker of harmonic stability, fully in line with the traditional symphonic deployment of tympani to reinforce the tonic. Within the extended narrative of the trio, however, the move makes perfect sense, as a reaction of the subjective presence to the mocking entry of the dotted figure. Oddly, then, and for the first time in the movement, the funeral march is thus invested with a disconcerting subjectivity on its return, as if the observed funeral procession has now been joined, with the incremental rise in pitch registering as a correspondingly heightened sense of reality.41 Odd, too, is how readily the absolute-music topic seems thus to acquiesce to the established subjectivity of the trio; the lack of protest may be taken as either a token of irresistible strength on the part of the trio’s subjectivity, or the continued weakened state of the funeral-march topic after the klezmer-like episode, or both. Or, perhaps, its oblivious detachment—programmatically, the self-absorbed lack of concern of the mourners for the world beyond the funeral march—now extends to the matter of its own key (link to example 21 again).

For the remainder of the movement, the subjective element invests briefly first in one side of the conflict and then the other. As the E-flat-minor section winds down, the tympani drop out and the violins take us back to D minor, playing col legno as a group but with interspersed solos in what is clearly a gesture of withdrawal (link to example 24). Almost immediately, the klezmer-like music enters in direct opposition to the “Bruder Martin” canon, brutally imposing a faster tempo and more raucous sensibility on the sedate funeral march (link to example 11 again). The implicit violence of the passage makes it a clear precursor for the outcry late in the Scherzo of the Second Symphony; as in the later movement (and this is also true for a similar moment in the Scherzo of the Third Symphony; link to example 25), however, the violence that results from the confrontation makes it clear that reconciliation is impossible.42 Yet this is not the only drama of the movement. As the music slows to the original march tempo, we hear a distinct echo of the song-quotation within one of the closing phrases of the klezmer episode (link to example 26). Although the phrase does not depart musically from the earlier episode (notwithstanding a somewhat different instrumental profile), the similar melodic contour within a suddenly more intimate environment involving unusual string textures (solo violin duet; violins doubled by cellos) enforces the connection; in addition, the brief splash of the Neapolitan (E-flat) serves as a striking marker of difference against the pedal D-A, recalling the key of the subjectively inflected version of the funeral march just heard. Within this brief moment of enhanced subjectivity, with its easy blending of klezmer elements with the “Bruder Martin” canon so soon after their recently demonstrated incompatibility, and with its easy resolution of the dissonant tonality of E-flat back into the D minor of the funeral march, we may find psychological closure for the movement. Significantly, the resolution this passage provides is wholly subjective, however, leaving the uneasy worldly tensions to play out to an indecisive conclusion, and leaving it to the finale, as noted, to achieve a more satisfying (and specifically Christian) closure.

The ambivalences of the First Symphony leave us with much the same basic questions as those of the Second Symphony, centering on Mahler’s allegiances within the cultural conflicts he presents in his music. Clearly, he ends in both cases in full alignment with the oppressive/seductive, Germanic/Christian element earlier resisted. Yet—to return to a set of questions asked earlier—how much more vital is a reading that gives pride of place to the starkly heroic image of a resisting outsider fighting against the tide of absorption into the dominant flow of a hostile culture? To this there is unlikely to be a definitive answer, for even today, a century later, this is precisely the tug-of-war that continues to play out, center-stage, in Mahler reception. Here is the opening sentence of a front-page Calendar review from a recent Los Angeles Times:

For some conductors, Mahler’s massive Second Symphony is a problem of cohesion—making hundreds of small parts and five extended movements into an organic entity that flows, that moves through disparate emotional and spiritual states without contradicting or distracting itself. (Cariaga F1)

This concern for “cohesion,” for projecting “an organic entity that flows … without contradicting or distracting itself”—the very notion, indeed, that a musical work must have a single “itself”—may be read, as we’ve indicated, as an acknowledgment that Mahler’s music resists full assimilation into the Germanic mainstream, that it bears throughout the trace of that resisting scream from the Scherzo of the Second Symphony, of that moment of serene disengagement late in the funeral march of the First. And we don’t quite know what to do with that resistance, particularly since it is the dissonance provided by those “disparate emotional and spiritual states” that more than anything else makes us care about Mahler. Surely, a large part of what we value in Mahler goes beyond the fact that he is a Jew who has nevertheless resurfaced within the mainstream of our concert halls; it is not so much that he provides yet another master for the post-Wagnerian Germanic canon, but rather that he stands antagonistically apart from that mainstream despite outer conformity.

And so we are left, like Leonard Bernstein, with a double image, of a Jewish composer who gives an overwhelmingly convincing performance of conversion to Christianity, but who does so within a narrative inflected indelibly with the perspective of Jewish resistance. It is almost as if the conscious self cannot escape unconscious affinities. It is almost—well, how else to say it?—it is almost Freudian. Perhaps, even if Freud had little use for music, the workings of music are not so different from the universe he did so much to open up to us, the world behind the conscious self. In any case, that’s where we seem to find Mahler’s Jewish identity, stubbornly unconverted and unassimilated, deeply embedded in what we might term his music’s unconscious.

Works Cited:

Abbate, Carolyn. Unsung Voices: Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1991.

Adorno, Theodor W. Mahler, A Musical Physiognomy. Trans. Edmund Jephcott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. Trans. of Mahler: Eine musikalische Physiognomik, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1971.

Applegate, Celia. “How German Is It? Nationalism and the Idea of Serious Music in the Early Nineteenth Century.” 19th–Century Music 21 (1998): 274–296.

Aschheim, Steven. “Nietzsche, Anti-Semitism and Mass Murder.” Culture and Catastrophe: German and Jewish Confrontations with National Socialism and Other Crises. London and New York: Macmillan and New York UP, 1996. 69–84.

—. The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890–1990. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Bauer-Lechner, Natalie. Recollections of Gustav Mahler. Trans. Dika Newlin. Ed. and annotated by Peter Franklin. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980. Trans. of Erinnerungen an Gustav Mahler. Leipzig, Vienna, and Zurich: E. P. Tal and Co. Verlag, 1923.

Beer, August. In Pester Lloyd 321 (21 November 1889).

Bein, Alex. Theodore Herzl: A Biography. Trans. Maurice Samuel. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1941.

Beller, Stephen. Herzl. London: Halban, 1991.

Bernstein, Leonard. “Mahler: His Time Has Come.” Findings. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973. 255–264. High Fidelity, September 1967.

—. “Who Is Gustav Mahler?” Facsimile handwritten script for “Young People’s Concert” given 7 February 1960. “The Leonard Bernstein Collection, ca. 1920-1989.” American Memory. Music Division, Library of Congress, 14 February 2000. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/lbhtml/lbhome.html.

—. “Who Is Gustav Mahler?” Facsimile edited typescript script for “Young People’s Concert” given 7 February 1960. “The Leonard Bernstein Collection, ca. 1920-1989.” American Memory. Music Division, Library of Congress, 14 February 2000. http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/lbhtml/lbhome.html.

Blaukopf, Kurt. Gustav Mahler. Trans. Inge Goodwin. New York: Praeger, 1973.

Brod, Max. “Gustav Mahlers Jüdische Melodien.” Anbruch 2 (1920): 378.

Cariaga, Daniel. “Mehta Pieces Together a Mahler Puzzle.” The Los Angeles Times 27 November 2000, F1.

Charcot, J. M. Leçons du mardi à la salpêtrière. Paris: Progrès médical, 1889.

Cohen, Israel. Theodore Herzl: Founder of Political Zionism. New York: T. Yoseloff, 1959.

Cooke, Deryck. Gustav Mahler: An Introduction to His Music. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980.

Dahlhaus, Carl. The Idea of Absolute Music. Trans. Roger Lustig. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989. Kassel, 1978.

—. “The Twofold Truth in Wagner’s Aesthetics: Nietzsche’s Fragment ‘On Music and Words.’” Between Romanticism and Modernism: Four Studies in the Music of the Later Nineteenth Century. Trans. Mary Whittall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. 1939. Munich, 1974.

Dowlding, William J. Beatlesongs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989.

Draughon, Francesca. “Mahler and the Fin-de-Siècle Imagination.” Diss. University of California, Los Angeles, anticipated completion 2002.

Fischer, Kurt R. “Nazism as Nietzschean Experiment.” Nietzsche-Studien l6 (1977): 116–122.

Floros, Constantin. Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies. Trans. Vernon Wicker. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1993. Trans. of Gustav Mahler III: Die Symphonien. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1985.

Franklin, Peter. The Life of Mahler. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997.

Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. New York: W. W. Norton, 1988.

—. A Godless Jew: Freud, Atheism, and the Making of Psychoanalysis. New Haven: Yale UP and Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1987.

Gilman, Sander L. The Case of Sigmund Freud: Medicine and Identity at the fin-de-siècle. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1993.

—. Difference and Pathology: Stereotypes of Sexuality, Race, and Madness. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 1985.